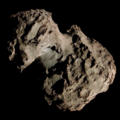

The Great Comet of 1901 photographed by Edward Emerson Barnard on 11 May 1901 | |

| Discovery [1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Viscara |

| Discovery site | Paysandú, Uruguay |

| Discovery date | 12 April 1901 |

| Designations | |

| 1901 I, 1901a [2] | |

| Orbital characteristics [3] | |

| Epoch | 18 May 1901 (JD 2415522.5) |

| Observation arc | 42 days |

| Number of observations | 54 |

| Aphelion | ~7,100 AU |

| Perihelion | 0.245 AU |

| Semi-major axis | ~3,500 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.99993 |

| Orbital period | ~210,900 years |

| Inclination | 131.077° |

| 111.038° | |

| Argument of periapsis | 203.046° |

| Mean anomaly | 0.0001° |

| Last perihelion | 24 April 1901 |

| TJupiter | –0.402 |

| Earth MOID | 0.4523 AU |

| Jupiter MOID | 0.1551 AU |

| Physical characteristics [4] | |

Mean radius | 4.77 km (2.96 mi) [a] |

| Comet total magnitude (M1) | 1.7 |

| Comet nuclear magnitude (M2) | 9.0 [5] |

| –1.5 (1901 apparition) [6] | |

The Great Comet of 1901, sometimes known as Comet Viscara, formally designated C/1901 G1 (and in the older nomenclature as 1901 I and 1901a), was a non-periodic comet which became bright in the spring of 1901. Visible exclusively (or almost exclusively) [7] from the Southern Hemisphere, it was discovered on the morning of April 12, 1901 as a naked-eye object of second magnitude with a short tail. On the day of perihelion passage, the comet's head was reported as deep yellowish in color, trailing a 10-degree tail. It was last seen by the naked eye on May 23.