| Cambridge movement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

| Date | December 1961 – 1964 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

The Cambridge movement was an American social movement in Dorchester County, Maryland, led by Gloria Richardson and the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee. Protests continued from late 1961 to the summer of 1964. The movement led to the desegregation of all schools, recreational areas, and hospitals in Maryland and the longest period of martial law within the United States since 1877. [1] Many cite it as the birth of the Black Power movement. [2]

Black residents of Cambridge had the right to vote, but were still discriminated against and lacked economic opportunities. Their homes did not have plumbing, some even living in "chicken shacks." And since the local segregated hospitals were white, black residents had to drive two hours to Baltimore for medical care. [3] They had the highest rates of unemployment. The black unemployment rate was four times higher than that of whites. The only two local factories, both defense contractors, had agreed not to hire any black workers, as long as the whites agreed not to unionize. All venues of entertainment, churches, cafes, and schools were segregated. Black schools received half as much funding as whites. [1]

On Christmas Eve of 1961, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Field Secretaries Reggie Robinson and Bill Hansen arrived and began organizing student protests. In 1962, the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee, (CNAC), was organized to run these protests. Gloria Richardson and Inez Grubb both became the co-chairs of the CNAC. It was the only affiliate of SNCC that was not student-led. [4] The CNAC began picketing any business which refused to hire blacks. They conducted sit-ins at lunch-counters which would not serve blacks. White mobs often disrupted protests such as these. Protests on Race Street, which separated the black and white communities, often became violent. Cleveland Sellers, who was a SNCC Field Secretary, later said, "By the time we got to town, Cambridge’s blacks had stopped extolling the virtues of passive resistance. Guns were carried as a matter of course and it was understood that they would be used." [3] Richardson defended such actions by blacks: "Self-defense may actually be a deterrent to further violence. Hitherto, the government has moved into conflict situations only when matters approach the level of insurrection." In the spring of 1963, over a period of seven weeks, Richardson and 80 other protesters were arrested. Tensions rose steadily and by June, blacks were rioting in the street. [4] Maryland Governor J. Millard Tawes met with the protesters at a local school. He offered to accelerate school desegregation, build public housing, and establish a biracial commission if they only cease the protests. The CNAC rejected the deal, and in response, he declared martial law and sent the National Guard to Cambridge. [5]

Possible violence close to the capitol brought Cambridge to the attention of the Kennedy Administration. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy began holding discussions with the CNAC. They, and the local city government, reached an agreement which would prevent possible violence. It would also desegregate public facilities, create provisions for public housing, and establish a human rights committee. It was called the "Treaty of Cambridge." But the agreement soon fell through as the local government demanded that it be passed by a local referendum. [3]

In May 1964, George Wallace, the segregationist Governor of Alabama, arrived in Cambridge to give a campaign speech. He had been invited by the DBCA, the city's primary business association. Black protesters soon appeared to protest his appearance and a riot occurred. [3]

Once the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed by Congress, the movement lost all momentum. The federal government had mandated everything that the CNAC had been fighting for. As protests ended, the National Guard withdrew. Gloria Richardson resigned from the CNAC and moved to New York City. [4]

The civil rights movement in the United States was a decades-long struggle by African Americans and their like-minded allies to end institutionalized racial discrimination, disenfranchisement and racial segregation in the United States. The movement has its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century, although the movement achieved its largest legislative gains in the mid-1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the human rights of all Americans.

Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, formerly known as H. Rap Brown, was the fifth chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s, and during a short-lived alliance between SNCC and the Black Panther Party, he served as their minister of justice.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African-Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama increased dramatically the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections. But by the mid-1960s the measured nature of the gains made, and the violence with which they were resisted, were generating dissent from the group's principles of non-violence, of white participation in the movement, and of field-driven, as opposed to national-office, leadership and direction. At the same time organizers were being lost to a de-segregating Democratic Party and to federally-funded anti-poverty programs. Following an aborted merger with the Black Panther Party in 1968, SNCC effectively dissolved. SNCC is nonetheless credited in its brief existence with breaking down barriers, both institutional and psychological, to the empowerment of African-American communities.

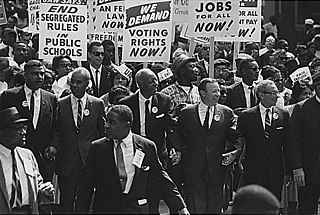

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday, August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rights of African Americans. At the march, Martin Luther King Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, delivered his historic "I Have a Dream" speech in which he called for an end to racism.

Kwame Ture was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global Pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the United States from the age of 11 and became an activist while attending the Bronx High School of Science. He eventually developed the Black Power movement, first while leading the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), later serving as the "Honorary Prime Minister" of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and lastly as a leader of the All-African People's Revolutionary Party (A-APRP).

James Morris Lawson Jr. is an American activist and university professor. He was a leading theoretician and tactician of nonviolence within the Civil Rights Movement. During the 1960s, he served as a mentor to the Nashville Student Movement and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was expelled from Vanderbilt University for his civil rights activism in 1960, and later served as a pastor in Los Angeles for 25 years.

Freedom Summer, or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African-American voters as possible in Mississippi. Blacks had been restricted from voting since the turn of the century due to barriers to voter registration and other laws. The project also set up dozens of Freedom Schools, Freedom Houses, and community centers in small towns throughout Mississippi to aid the local black population.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

Ella Josephine Baker was an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and the South, she worked alongside some of the most noted civil rights leaders of the 20th century, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr. She also mentored many emerging activists, such as Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael, Rosa Parks, and Bob Moses, whom she first mentored as leaders in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Gloria Richardson Dandridge is best known as the leader of the Cambridge Movement, a civil rights struggle in the early 1960s in Cambridge, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore. Recognized as a major figure in the Civil Rights Movement at the time, she was one of the signatories to "The Treaty of Cambridge", signed in July 1963 with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, and state and local officials after the riot the month before.

Clayborne Carson is a professor of history at Stanford University, and director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. Since 1985 he has directed the Martin Luther King Papers Project, a long-term project to edit and publish the papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Cambridge riots of 1963 were race riots that occurred during the summer of 1963 in Cambridge, a small city on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The riots emerged during the Civil Rights Movement, locally led by Gloria Richardson and the local chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. They were opposed by segregationists including the police.

The Cambridge riot of 1967 was one of 159 race riots that swept cities in the United States during the "Long Hot Summer of 1967". This riot occurred on July 24, 1967 in Cambridge, Maryland, a county seat on the Eastern Shore. For years racial tension had been high in Cambridge, where blacks had been limited to second-class status. Activists had conducted protests since 1961, and there was a riot in June 1963 after the governor imposed martial law. "The Treaty of Cambridge" was negotiated among federal, state, and local leaders in July 1963, initiating integration in the city prior to passage of federal civil rights laws. The events of 1967 were much more destructive to the city.

Judy Richardson is an American documentary filmmaker, and civil rights activist. She was Distinguished Visiting Lecturer of Africana Studies, at Brown University.

Charles E. "Charlie" Cobb Jr. is a journalist, professor, and former activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Along with several veterans of SNCC, Cobb established and operated the African-American bookstore Drum and Spear in Washington, D.C. from 1968 to 1974. Currently he is a senior analyst at allAfrica.com and a visiting professor at Brown University.

Diversity of tactics is a phenomenon wherein a social movement makes periodic use of force for disruptive or defensive purposes, stepping beyond the limits of nonviolence, but also stopping short of total militarization. It also refers to the theory which asserts this to be the most effective strategy of civil disobedience for social change. Diversity of tactics may promote nonviolent tactics, or armed resistance, or a range of methods in between, depending on the level of repression the political movement is facing. It sometimes claims to advocate for "forms of resistance that maximize respect for life".

Samuel Leamon Younge Jr. was a civil rights and voting rights activist who was murdered for trying to desegregate a "whites only" restroom. Younge was an enlisted service member in the United States Navy, where he served for two years before being medically discharged. Younge was an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and a leader of the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League.

This is a timeline of the 1954 to 1968 civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for African Americans. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally established racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

The sit-in movement, sit-in campaign or student sit-in movement, were a wave of sit-ins that followed the Greensboro sit-ins on February 1, 1960 in North Carolina. The sit-in movement employed the tactic of nonviolent direct action and was a pivotal event during the Civil Rights Movement.

The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), also known as the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP) or Black Panther party, was an American political party founded during 1965 in Lowndes County, Alabama. The independent third party was formed by local African-American citizens and staff members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael. On March 23, 1965, as the march from from Selma to Montgomery took place, Carmichael and some in SNCC who were participants declined to continue marching after reaching Lowndes County and decided to instead stop and talk with local residents. Carmichael and the other SNCC activists who stayed with him in Lowndes County were inspired to create the LCFO with local activist John Hulett and other local leaders after word spread that Carmichael avoided arrest from two officers who ordered him to leave a school where he was registering voters after he challenging them to do so.