Related Research Articles

The civil rights movement was a social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United States. The campaign lasted from December 5, 1955—the Monday after Rosa Parks, an African-American woman, was arrested for her refusal to surrender her seat to a white person—to December 20, 1956, when the federal ruling Browder v. Gayle took effect, and led to a United States Supreme Court decision that declared the Alabama and Montgomery laws that segregated buses were unconstitutional.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about equality for all people regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, religion or ethnic background." To combat discriminatory policies regarding interstate travel, CORE participated in Freedom Rides as college students boarded Greyhound Buses headed for the Deep South. As the influence of the organization grew, so did the number of chapters, eventually expanding all over the country. Despite CORE remaining an active part of the fight for change, some people have noted the lack of organization and functional leadership has led to a decline of participation in social justice.

Kenneth Bancroft Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark were American psychologists who as a married team conducted research among children and were active in the Civil Rights Movement. They founded the Northside Center for Child Development in Harlem and the organization Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU). Kenneth Clark was also an educator and professor at City College of New York, and first Black president of the American Psychological Association.

Robert Franklin Williams was an American civil rights leader and author best known for serving as president of the Monroe, North Carolina chapter of the NAACP in the 1950s and into 1961. He succeeded in integrating the local public library and swimming pool in Monroe. At a time of high racial tension and official abuses, Williams promoted armed Black self-defense in the United States. In addition, he helped gain support for gubernatorial pardons in 1959 for two young African-American boys who had received lengthy reformatory sentences in what was known as the Kissing Case of 1958.

Diane Judith Nash is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

Yuri Kochiyama was an American civil rights activist. Influenced by her Japanese-American family's experience in an American internment camp, her association with Malcolm X, and her Maoist and Islamic beliefs, she advocated for many causes, including black separatism, the anti-war movement, reparations for Japanese-American internees, and the rights of political prisoners.

Charlene Alexander Mitchell was an American international socialist, feminist, labor and civil rights activist. In 1968, she became the first Black woman candidate for President of the United States.

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts of African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama.

Gloria Richardson Dandridge was an American civil rights activist best known as the leader of the Cambridge movement, a civil rights action in the early 1960s in Cambridge, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore. Recognized as a major figure in the Civil Rights Movement, she was one of the signatories to "The Treaty of Cambridge", signed in July 1963 with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, and state and local officials. It was an effort at reconciliation and commitment to change after a riot the month before.

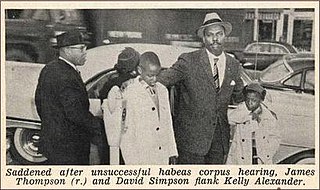

The Kissing Case was the arrest, conviction and lengthy sentencing of two prepubescent African-American boys in 1958 in Monroe, North Carolina. A white girl kissed each of them on the cheek and later told her mother, who accused the boys of rape. The boys were then charged by authorities with molestation. Civil rights activists became involved in representing the boys. The boys were arrested in October 1958, separated from their parents for a week, beaten and threatened by investigators, then sentenced by a Juvenile Court judge.

Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from its earliest days in 1960 until her death in October 1967. She served the organization as an activist in the field and as an administrator in the Atlanta central office. She eventually succeeded James Forman as SNCC's executive secretary and was the only woman ever to serve in this capacity. She was well respected by her SNCC colleagues and others within the movement for her work ethic and dedication to those around her. SNCC Freedom Singer Matthew Jones recalled, "You could feel her power in SNCC on a daily basis". Jack Minnis, director of SNCC's opposition research unit, insisted that people could not fool her. Over the course of her life, she served 100 days in prison for the movement.

Anna Arnold Hedgeman was an African-American civil rights leader, politician, educator, and writer. Under President Harry Truman, Hedgeman served as executive director of the National Council for a Permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission, having worked on his presidential campaign. She was also appointed to the cabinet of New York City mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr., becoming the first African-American woman to hold a cabinet post in New York. Hedgeman was a major advocate for both minorities and the poor in New York City. She also served as a consultant for many companies and entities on racial issues, and late in her life founded Hedgeman Consultant Services. She was among the organizers of the 1963 March on Washington. Throughout her many years involved in the civil rights movement, she befriended Dorothy Height.

The Freedom Singers originated as a quartet formed in 1962 at Albany State College in Albany, Georgia. After folk singer Pete Seeger witnessed the power of their congregational-style of singing, which fused black Baptist a cappella church singing with popular music at the time, as well as protest songs and chants. Churches were considered to be safe spaces, acting as a shelter from the racism of the outside world. As a result, churches paved the way for the creation of the freedom song. After witnessing the influence of freedom songs, Seeger suggested The Freedom Singers as a touring group to the SNCC executive secretary James Forman as a way to fuel future campaigns. Intrinsically connected, their performances drew aid and support to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the emerging civil rights movement. As a result, communal song became essential to empowering and educating audiences about civil rights issues and a powerful social weapon of influence in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. Their most notable song “We Shall Not Be Moved” translated from the original Freedom Singers to the second generation of Freedom Singers, and finally to the Freedom Voices, made up of field secretaries from SNCC. "We Shall Not Be Moved" is considered by many to be the "face" of the Civil Rights movement. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Since the Freedom Singers were so successful, a second group was created called the Freedom Voices.

Conrad Joseph Lynn was an African-American civil rights lawyer and activist known for providing legal representation for activists, including many unpopular defendants. Among the causes he supported as a lawyer were civil rights, Puerto Rican nationalism, and opposition to the draft during both World War II and the Vietnam War. The controversial defendants he represented included civil rights activist Robert F. Williams and Black Panther leader H. Rap Brown.

Patricia Stephens Due was one of the leading African-American civil rights activists in the United States, especially in her home state of Florida. Along with her sister Priscilla and others trained in nonviolent protest by CORE, Due spent 49 days in one of the nation's first jail-ins, refusing to pay a fine for sitting in a Woolworth's "White only" lunch counter in Tallahassee, Florida in 1960. Her eyes were damaged by tear gas used by police on students marching to protest such arrests, and she wore dark glasses for the rest of her life. She served in many leadership roles in CORE and the NAACP, fighting against segregated stores, buses, theaters, schools, restaurants, and hotels, protesting unjust laws, and leading one of the most dangerous voter registration efforts in the country in northern Florida in the 1960s.

Mae Bertha Carter was an activist during the Civil Rights Movement from Drew, Mississippi.

McCree L. Harris was an American educator and political activist leader. Harris worked at the all-Black Monroe Comprehensive High School, where she taught Latin, French, and Social Studies. She is best known for her participation with the Freedom Singers and for encouraging her students' involvement in the Civil Rights Movement through voter registration marches and by leading groups of students to downtown Albany, Georgia, after school hours to test desegregation rulings at local stores and movie theaters.

Bonita Williams was a British West-Indian Communist Party leader, poet, and civil rights activist in Harlem, New York during the Great Depression in the 1930s. During this time, she wrote several poems and gave speeches focusing on black suffrage and workers' rights in the context of racial discrimination and class inequity. In addition, Williams served as the leader of several Harlem-based organizations, namely the Harlem Unemployment Council, Harlem Tenants' League, Harlem Action Committee against the High Cost of Living, and League of Struggle for Negro Rights (LSNR).

References

- ↑ "THE MAE MALLORY COLLECTION Papers, 1961–1967", Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

- ↑ Foong, Yie, M.A., "Frame up in Monroe: The Mae Mallory Story", Sarah Lawrence College.

- 1 2 3 4 Melissa F. Weiner, Power, Protest, and the Public Schools: Jewish and African American Struggles in New York City (Rutgers University Press, 2010) pp. 51-66.

- 1 2 Jeanette Merrill and Rosemary Neidenberg, "Mae Mallory: unforgettable freedom fighter promoted self-defense", Workers World, February 26, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Farmer, Ashley D (2018-10-15). ""All the Progress to Be Made Will Be Made by Maladjusted Negroes": Mae Mallory, Black Women's Activism, and the Making of the Black Radical Tradition". Journal of Social History. 53 (2): 508–530. doi:10.1093/jsh/shy085. ISSN 1527-1897.

- 1 2 3 Burrell, Kristopher Bryan (2020-12-31), "3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals", The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North, New York University Press, pp. 89–112, doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479854318.003.0006, ISBN 978-1-4798-5431-8

- ↑ Patrick G. Coy (ed.), Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change (Emerald Group, 2011), pp. 305-312.

- ↑ Adina Back, "Exposing the Whole Segregation Myth: The Harlem Nine and New York City Schools" in Jeanne Theoharis, Komozi Woodard (eds), Freedom North: Black freedom struggles outside the South, 1940-1980 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), pp. 65-91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Mallory, Mae (1964). MEMO FROM A MONROE JAIL (2 ed.). Freedomways.

- ↑ A. T. Simpson, "After one year of hell Mae Mallory is still a champion", Workers World, October 26, 1962.

- ↑ Farmer, Ashley (2016-06-03). "Mae Mallory: Forgotten Black Power Intellectual". AAIHS. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ↑ Farmer, Ashley D. (Winter 2019). ""All the Progress to Be Made Will Be Made by Maladjusted Negroes": Mae Mallory, Black Women's Activism, and the Making of the Black Radical Tradition". Journal of Social History. 53 (2): 508–530. doi:10.1093/jsh/shy085.

- ↑ Ward Churchill; Jim Vander Wall (2002). The COINTELPRO papers: documents from the FBI's secret wars against dissent in the United States. South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-648-7.

- ↑ Kevin Kelly Gaines, American Africans in Ghana: Black expatriates and the civil rights era (University North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 146–149.

- ↑ Diane Carol Fujino (2005). Heartbeat of Struggle: the revolutionary life of Yuri Kochiyama . University of Minnesota Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8166-4593-0.

- ↑ Ann Rowe Seaman (2005). America's Most Hated Woman: the life and gruesome death of Madalyn Murray O'Hair. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1644-5.

- ↑ "Some Personal Reflections on the Sixth Pan-African Congress", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Black World, October 1974.

- ↑ Mae Mallory Papers. Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

- ↑ Note for the references: A.T. Simpson was an alias for Clarence H. Seniors, Chairman of Cleveland's Monroe Defense Committee