Chaubunagungamaug Reservation | |

|---|---|

State Indian Reservation | |

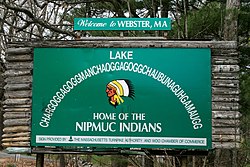

Sign with the 14-syllable long form alternate name for Lake Chaubunagungamaug that also acknowledges the Nipmuck presence in the town. | |

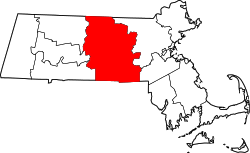

The Town of Webster, which contained the original reservation, within Worcester County and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts underneath the Town Seal. | |

| Coordinates: 42°01′27″N71°52′38″W / 42.02417°N 71.87722°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Worcester |

| Praying Town of Chabanakongkomun | 1674-1675 [1] |

| Dudley Indian (Chaubunagungamaug) Reservation | c. 1682-1887 [2] |

| Chaubungaungmaug Reservation | 1981–present [3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council meeting, with members elected from certain family lines. |

| • Sachem | None at this time |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.5 acres (1.0 ha) |

| Elevation | 505 ft (154 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

• Total | 0 |

| • Density | 0.0/sq mi (0.0/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 01570 |

| Area code | 508 / 774 |

| Website | Official CBNI Website |

The Chaubunagungamaug Reservation refers to the small parcel of land located in the town of Thompson, Connecticut, close to the border with the town of Webster, Massachusetts, and within the bounds of Lake Chaubunagungamaug (Webster Lake) to the east and the French River to the west. The reservation is used by the descendants of the Nipmuck Indians of the previous reservation, c. 1682–1869, that existed in the same area, who now identify as the Webster/Dudley Band of the Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck. [4]

Contents

The reservation only consists of 2.5 acres (1.0 hectare), and does not support a permanent population. It does serve as a meeting place and cultural center for Webster/Dudley Band of the Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck. The land is also used as a place for the reinterment of local Native American remains. [5] The tribe, and its reservation, are recognized in Massachusetts, but both lack recognition in Connecticut and at the federal level. [6] [7]