A miko, or shrine maiden, is a young priestess who works at a Shinto shrine. Miko were once likely seen as shamans, but are understood in modern Japanese culture to be an institutionalized role in daily life, trained to perform tasks, ranging from sacred cleansing to performing the sacred Kagura dance.

In Japanese, Kokuji or Wasei kanji are kanji created in Japan rather than borrowed from China. Like most Chinese characters, they are primarily formed by combining existing characters - though using combinations that are not used in Chinese.

A Shinto shrine is a structure whose main purpose is to house ("enshrine") one or more kami, the deities of the Shinto religion.

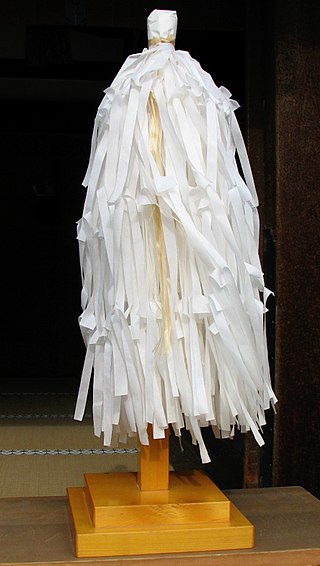

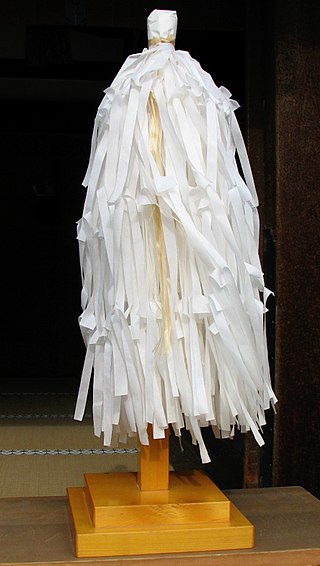

An ōnusa or simply nusa or Taima is a wooden wand traditionally used in Shinto purification rituals.

A sacred tree or holy tree is a tree which is considered to be sacred, or worthy of spiritual respect or reverence. Such trees appear throughout world history in various cultures including the ancient Hindu mythology, Greek, Celtic and Germanic mythologies. They also continue to hold profound meaning in contemporary culture in places like Japan (shinboku), Korea, India, and the Philippines, among others. Tree worship is core part of religions which include aspects of animism as core elements of their belief, which is the eco-friendly belief that trees, forests, rivers, mountains, etc have a life force and need to be conserved and used in a sustainable manner.

Himorogi in Shinto terminology are sacred spaces or altars used to worship. In their simplest form, they are square areas with green bamboo or sakaki at the corners without architecture. These in turn support sacred ropes (shimenawa) decorated with streamers called shide. A branch of sakaki or some other evergreen at the center acts as a yorishiro, a physical representation of the presence of the kami, a being which is in itself incorporeal.

Tamagushi is a form of Shinto offering made from a sakaki-tree branch decorated with shide strips of washi paper, silk, or cotton. At Japanese weddings, funerals, miyamairi and other ceremonies at Shinto shrines, tamagushi are ritually presented to the kami by parishioners, shrine maidens or kannushi priests.

Toyouke-Ōmikami is the goddess of agriculture and industry in the Shinto religion. Originally enshrined in the Tanba region of Japan, she was called to reside at Gekū, Ise Shrine, about 1,500 years ago at the age of Emperor Yūryaku to offer sacred food to Amaterasu Ōmikami, the Sun Goddess.

Okami in the Kojiki, or in the Nihon Shoki: Kuraokami (闇龗) or Okami (龗), is a legendary Japanese dragon and Shinto deity of rain and snow. In Japanese mythology, the sibling progenitors Izanagi and Izanami gave birth to the islands and gods of Japan. After Izanami died from burns during the childbirth of the fire deity Kagu-tsuchi, Izanagi was enraged and killed his son. Kagutsuchi's blood or body, according to differing versions of the legend, created several other deities, including Kuraokami.

Ōasahiko Shrine is a Shinto shrine in the Ōasachō-Bandō neighborhood of the city of Naruto, Tokushima Prefecture, Japan. It is one of the shrines claiming the title of ichinomiya of former Awa Province. The main festival of the shrine is held annually on November 1.

A yorishiro (依り代/依代/憑り代/憑代) in Shinto terminology is an object capable of attracting spirits called kami, thus giving them a physical space to occupy during religious ceremonies. Yorishiro are used during ceremonies to call the kami for worship. The word itself literally means "approach substitute". Once a yorishiro actually houses a kami, it is called a shintai. Ropes called shimenawa decorated with paper streamers called shide often surround yorishiro to make their sacredness manifest. Persons can play the same role as a yorishiro, and in that case are called yorimashi or kamigakari.

This is the glossary of Shinto, including major terms on the subject. Words followed by an asterisk (*) are illustrated by an image in one of the photo galleries.

In Shinto, shintai, or go-shintai when the honorific prefix go- is used, are physical objects worshipped at or near Shinto shrines as repositories in which spirits or kami reside. Shintai used in Shrine Shinto can be also called mitamashiro.

Founding of the Nation is a 1929 oil painting by Japanese yōga artist Kawamura Kiyoo (1854–1932). Based on the myth of the cave of the sun goddess from the Kojiki, the painting resides at the Musée Guimet in Paris, where it is known as Le coq blanc or The white cockerel.

A shinboku (神木) is a tree or forest worshipped as a shintai – a physical object of worship at or near a Shinto shrine, worshipped as a repository in which spirits or kami reside. They are often distinctly visible due to the shimenawa wrapped around them.

Kannagi are shamans in Shinto. Unlike the similar term miko, the term is gender neutral. The term has a few different writing styles, one being 巫, which is a shared kanji character as used for the Chinese Wu shaman.

Kannabi (神奈備), also kaminabi or kamunabi, refers to a region in Shinto that is a shintai itself, or hosts a kami. They are generally either mountains or forests. Nachi Falls is considered a kannabi, as is Mount Miwa.

Chinju-no-mori (鎮守の森) are forests established and maintained in or around shrines (Chinjugami) in Japan, surrounding temples, Sando, and places of worship.

Masakaki (真榊) is an object used in Shinto rituals. It is put on both sides of a table where the event takes place. Masakaki is made with branches of a tree called Sakaki. These branches are attached to the top of colorful cloth banners. The banners are in five colors - green, yellow, red, white, and blue.