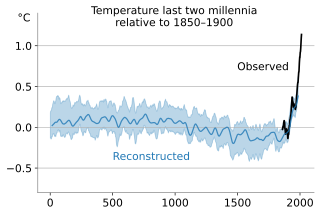

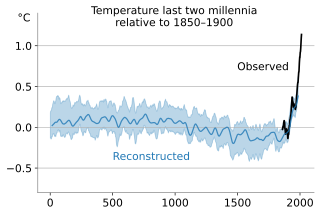

Climate variability includes all the variations in the climate that last longer than individual weather events, whereas the term climate change only refers to those variations that persist for a longer period of time, typically decades or more. In addition to the general meaning in which climate change may refer to any time in Earth's history, the term is commonly used to describe the climate change that is now underway. In the time since the Industrial Revolution, the climate has increasingly been affected by human activities that are causing global warming and climate change.

In the study of past climates ("paleoclimatology"), climate proxies are preserved physical characteristics of the past that stand in for direct meteorological measurements and enable scientists to reconstruct the climatic conditions over a longer fraction of the Earth's history. Reliable global records of climate only began in the 1880s, and proxies provide the only means for scientists to determine climatic patterns before record-keeping began.

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent. Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Europe, and Asia and profoundly affected Earth's climate by causing drought, desertification, and a large drop in sea levels. According to Clark et al., growth of ice sheets commenced 33,000 years ago and maximum coverage was between 26,500 years and 19–20,000 years ago, when deglaciation commenced in the Northern Hemisphere, causing an abrupt rise in sea level. Decline of the West Antarctica ice sheet occurred between 14,000 and 15,000 years ago, consistent with evidence for another abrupt rise in the sea level about 14,500 years ago.

The Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project is a project, somewhat along the lines of AMIP or CMIP, to coordinate and encourage the systematic study of atmospheric general circulation models (AGCMs) and to assess their ability to simulate large climate changes such as those that occurred in the distant past. Project goals include identifying common responses of AGCMs to imposed paleoclimate "boundary conditions," understanding the differences in model responses, comparing model results with paleoclimate data, and providing AGCM results for use in helping in the analysis and interpretation of paleoclimate data. PMIP is initially focussing on the mid-Holocene (6,000 years before present) and the Last Glacial Maximum (21,000 yr BP) because climatic conditions were remarkably different at those times, and because relatively large amounts of paleoclimate data exist for these periods. The major "forcing" factors are also relatively well known at these times. Some of the paleoclimate features simulated by models in previous studies seem consistent with paleoclimatic data, but others do not. One of the goals of PMIP is to determine which results are model-dependent. The PMIP experiments are limited to studying the equilibrium response of the atmosphere (and such surface characteristics as snow cover) to changes in boundary conditions (e.g., insolation, ice-sheet distribution, CO2 concentration, etc.)

The geologic temperature record are changes in Earth's environment as determined from geologic evidence on multi-million to billion (109) year time scales. The study of past temperatures provides an important paleoenvironmental insight because it is a component of the climate and oceanography of the time.

The Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO) was a warm period that occurred in the interval roughly 9,000 to 5,000 years ago BP, with a thermal maximum around 8000 years BP. It has also been known by many other names, such as Altithermal, Climatic Optimum, Holocene Megathermal, Holocene Optimum, Holocene Thermal Maximum, Hypsithermal, and Mid-Holocene Warm Period.

Climate sensitivity is a measure of how much Earth's surface will cool or warm after a specified factor causes a change in its climate system, such as how much it will warm for a doubling in the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration. In technical terms, climate sensitivity is the average change in global mean surface temperature in response to a radiative forcing, which drives a difference between Earth's incoming and outgoing energy. Climate sensitivity is a key measure in climate science, and a focus area for climate scientists, who want to understand the ultimate consequences of anthropogenic global warming.

Throughout Earth's climate history (Paleoclimate) its climate has fluctuated between two primary states: greenhouse and icehouse Earth. Both climate states last for millions of years and should not be confused with glacial and interglacial periods, which occur as alternate phases within an icehouse period and tend to last less than 1 million years. There are five known Icehouse periods in Earth's climate history, which are known as the Huronian, Cryogenian, Andean-Saharan, Late Paleozoic, and Late Cenozoic glaciations. The main factors involved in changes of the paleoclimate are believed to be the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide, changes in Earth's orbit, long-term changes in the solar constant, and oceanic and orogenic changes from tectonic plate dynamics. Greenhouse and icehouse periods have played key roles in the evolution of life on Earth by directly and indirectly forcing biotic adaptation and turnover at various spatial scales across time.

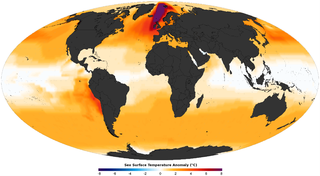

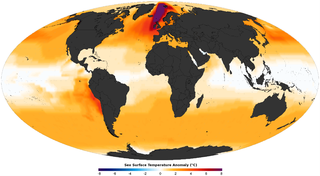

Polar amplification is the phenomenon that any change in the net radiation balance tends to produce a larger change in temperature near the poles than in the planetary average. This is commonly referred to as the ratio of polar warming to tropical warming. On a planet with an atmosphere that can restrict emission of longwave radiation to space, surface temperatures will be warmer than a simple planetary equilibrium temperature calculation would predict. Where the atmosphere or an extensive ocean is able to transport heat polewards, the poles will be warmer and equatorial regions cooler than their local net radiation balances would predict. The poles will experience the most cooling when the global-mean temperature is lower relative to a reference climate; alternatively, the poles will experience the greatest warming when the global-mean temperature is higher.

This is a list of climate change topics.

During the Pliocene epoch, the Earth's climate became cooler and drier, as well as more seasonal, marking a transition between the relatively warm Miocene to the cold Quaternary.

Climate change feedbacks are important in the understanding of global warming because feedback processes amplify or diminish the effect of each climate forcing, and so play an important part in determining the climate sensitivity and future climate state. Feedback in general is the process in which changing one quantity changes a second quantity, and the change in the second quantity in turn changes the first. Positive feedback amplifies the change in the first quantity while negative feedback reduces it.

Climate change can affect tropical cyclones in a variety of ways: an intensification of rainfall and wind speed, a decrease in overall frequency, an increase in the frequency of very intense storms and a poleward extension of where the cyclones reach maximum intensity are among the possible consequences of human-induced climate change. Tropical cyclones use warm, moist air as their fuel. As climate change is warming ocean temperatures, there is potentially more of this fuel available. Between 1979 and 2017, there was a global increase in the proportion of tropical cyclones of Category 3 and higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The trend was most clear in the North Atlantic and in the Southern Indian Ocean. In the North Pacific, tropical cyclones have been moving poleward into colder waters and there was no increase in intensity over this period. With 2 °C (3.6 °F) warming, a greater percentage (+13%) of tropical cyclones are expected to reach Category 4 and 5 strength. A 2019 study indicates that climate change has been driving the observed trend of rapid intensification of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. Rapidly intensifying cyclones are hard to forecast and therefore pose additional risk to coastal communities.

A global warming hiatus, also sometimes referred to as a global warming pause or a global warming slowdown, is a period of relatively little change in globally averaged surface temperatures. In the current episode of global warming many such 15-year periods appear in the surface temperature record, along with robust evidence of the long-term warming trend. Such a "hiatus" is shorter than the 30-year periods that climate is classically averaged over.

Gabriele Clarissa Hegerl is Professor of Climate System Science at the University of Edinburgh School of GeoSciences. Prior to 2007 she held research positions at Texas A&M University and at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment, during which time she was a co-ordinating lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth and Fifth Assessment Report.

Patterns of solar irradiance and solar variation have been a main driver of climate change over the millions to billions of years of the geologic time scale, but their role in recent warming is insignificant. Evidence that this is the case comes from analysis on many timescales and from many sources, including: direct observations; composites from baskets of different proxy observations; and numerical climate models. On millennial timescales, paleoclimate indicators have been compared to cosmogenic isotope abundances as the latter are a proxy for solar activity. These have also been used on century times scales but, in addition, instrumental data are increasingly available and show that, for example, the temperature fluctuations do not match the solar activity variations and that the commonly-invoked association of the Little Ice Age with the Maunder minimum is far too simplistic as, although solar variations may have played a minor role, a much bigger factor is known to be Little Ice Age volcanism. In recent decades observations of unprecedented accuracy, sensitivity and scope have become available from spacecraft and show unequivocally that recent global warming is not caused by changes in the Sun.

Axel Timmermann is a German climate physicist and oceanographer with an interest in climate dynamics, human migration, dynamical systems' analysis, ice-sheet modeling and sea level. He served a co-author of the IPCC Third Assessment Report and a lead author of IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. His research has been cited over 18,000 times and has an h-index of 70 and i10-index of 161. In 2017, he became a Distinguished Professor at Pusan National University and the founding Director of the Institute for Basic Science Center for Climate Physics. In December 2018, the Center began to utilize a 1.43-petaflop Cray XC50 supercomputer, named Aleph, for climate physics research.

Cyclonic Niño is a climatological phenomenon that has been observed in climate models where tropical cyclone activity is increased. Increased tropical cyclone activity mixes ocean waters, introducing cooling in the upper layer of the ocean that quickly dissipates and warming in deeper layers that lasts considerably more, resulting in a net warming of the ocean.

Bette Otto-Bliesner is an earth scientist known for her modeling of Earth's past climate and its changes over different geological eras.

Global paleoclimate indicators are the proxies sensitive to global paleoclimatic environment changes. They are mostly derived from marine sediments. Paleoclimate indicators derived from terrestrial sediments, on the other hand, are commonly influenced by local tectonic movements and paleogeographic variations. Factors governing the earth climate system include plate tectonics, which controls the configuration of continents, the interplay between the atmosphere and the ocean, and the earth's orbital characteristics. Global paleoclimate indicators are established based on the information extracted from the analyses of geologic materials, including biological, geochemical and mineralogical data preserved in marine sediments. Indicators are generally grouped into three categories; paleontological, geochemical and lithological.