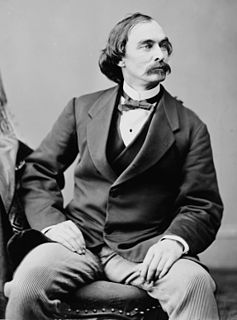

Life and career

Born in Philadelphia, Kane was the son of John Kintzing Kane, a U.S. district judge, and Jane Duval Leiper. His brother was attorney, diplomat, abolitionist, and Civil War general Thomas L. Kane. Kane graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1842. On September 14, 1843, he became Assistant Surgeon in the Navy. He served in the China Commercial Treaty mission under Caleb Cushing, in the Africa Squadron, [1] and in the United States Marine Corps during the Mexican–American War. One battle that Kane fought in was at Nopalucan on January 6, 1848. At Nopalucan, he captured, befriended and saved the life of Mexican General Antonio Gaona and the General's wounded son. [2]

Philadelphia, sometimes known colloquially as Philly, is the largest city in the U.S. state and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the sixth-most populous U.S. city, with a 2017 census-estimated population of 1,580,863. Since 1854, the city has been coterminous with Philadelphia County, the most populous county in Pennsylvania and the urban core of the eighth-largest U.S. metropolitan statistical area, with over 6 million residents as of 2017. Philadelphia is also the economic and cultural anchor of the greater Delaware Valley, located along the lower Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, within the Northeast megalopolis. The Delaware Valley's population of 7.2 million ranks it as the eighth-largest combined statistical area in the United States.

John Kintzing Kane was an American politician, attorney and jurist. Kane was noted for his political affiliation with President Andrew Jackson and for an 1855 pro-slavery legal decision related to the freeing of Jane Johnson and application of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

Abolitionism in the United States was the movement before and during the American Civil War to end slavery in the United States. In the Americas and western Europe, abolitionism was a movement to end the Atlantic slave trade and set slaves free. In the 17th century, enlightenment thinkers condemned slavery on humanistic grounds and English Quakers and some Evangelical denominations condemned slavery as un-Christian. At that time, most slaves were Africans, but thousands of Native Americans were also enslaved. In the 18th century, as many as six million Africans were transported to the Americas as slaves, at least a third of them on British ships to North America. The colony of Georgia originally abolished slavery within its territory, and thereafter, abolition was part of the message of the First Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s in the Thirteen Colonies.

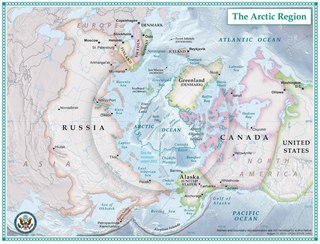

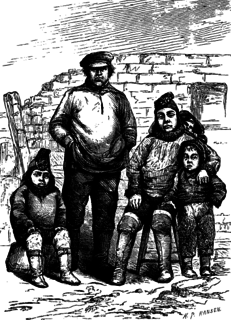

Kane was appointed senior medical officer of the Grinnell Arctic expedition of 1850–1851 under the command of Edwin de Haven, which searched unsuccessfully for the lost expedition of Sir John Franklin. [3] During this expedition, the crew discovered Sir John Franklin's first winter camp. Kane then organized and headed the Second Grinnell expedition which sailed from New York on May 31, 1853, and wintered in Rensselaer Bay. Though suffering from scurvy, and at times near death, he pushed on and charted the coasts of Smith Sound and the Kane Basin, penetrating farther north than any other explorer had done up to that time. At Cape Constitution he discovered the ice-free Kennedy Channel, later followed by Isaac Israel Hayes, Charles Francis Hall, Augustus Greely, and Robert E. Peary in turn as they drove toward the North Pole.

The First Grinnell Expedition of 1850 was the first American effort, financed by Henry Grinnell, to determine the fate of the lost Franklin Polar Expedition. Led by Lieutenant Edwin De Haven, the team explored the accessible areas along Franklin's proposed route. In coordination with British expeditions, they identified the remains of Franklin's Beechy Island winter camp, providing the first solid clues to Franklin's activities during the winter of 1845 before becoming icebound themselves.

Franklin's lost expedition was a British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Franklin had served on three previous Arctic expeditions, the latter two as commanding officer. His fourth and last, undertaken when he was 59, was meant to traverse the last unnavigated section of the Northwest Passage. After a few early fatalities, the two ships became icebound in Victoria Strait near King William Island in the Canadian Arctic, in what is today the territory of Nunavut. The entire expedition, comprising 129 men including Franklin, was lost.

The Second Grinnell expedition of 1853–1855 was an American effort, financed by Henry Grinnell, to determine the fate of the Franklin's lost expedition. Led by Elisha Kent Kane, the team explored areas northwest of Greenland, now called Grinnell Land.

In 1852, Kane met the Fox sisters, famous for their spirit rapping séances, and he became enamored with the middle sister, Margaret. Kane was convinced that the sisters were frauds, and sought to reform Margaret. She would later claim that they were secretly married in 1856—she changed her name to Margaret Fox Kane—and engaged the family in lawsuits over his will. (After Kane's death, Margaret converted to the Roman Catholic faith, but she would eventually return to spiritualism.) [5] [6] [1]

The Fox sisters were three sisters from New York who played an important role in the creation of Spiritualism: Leah (1814–1890), Margaretta (1833–1893) and Catherine(also called Kate ) Fox (1837–1892). The two younger sisters used "rappings" to convince their older sister and others that they were communicating with spirits. Their older sister then took charge of them and managed their careers for some time. They all enjoyed success as mediums for many years.

Spiritualism is a religious movement based on the belief that the spirits of the dead exist and have both the ability and the inclination to communicate with the living. The afterlife, or the "spirit world", is seen by spiritualists, not as a static place, but as one in which spirits continue to evolve. These two beliefs — that contact with spirits is possible, and that spirits are more advanced than humans — lead spiritualists to a third belief, that spirits are capable of providing useful knowledge about moral and ethical issues, as well as about the nature of God. Some spiritualists will speak of a concept which they refer to as "spirit guides"—specific spirits, often contacted, who are relied upon for spiritual guidance. Spiritism, a branch of spiritualism developed by Allan Kardec and today practiced mostly in Continental Europe and Latin America, especially in Brazil, emphasizes reincarnation.

Kane finally abandoned the icebound brig Advance on May 20, 1855 and made an 83-day march of indomitable courage to Upernavik. The party, carrying the invalids, lost only one man. Kane and his men were saved by a sailing ship. Kane returned to New York on October 11, 1855 and the following year published his two-volume Arctic Explorations.

A brig is a sailing vessel with two square-rigged masts. During the Age of Sail, brigs were seen as fast and maneuverable and were used as both naval warships and merchant vessels. They were especially popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Brigs fell out of use with the arrival of the steam ship because they required a relatively large crew for their small size and were difficult to sail into the wind. Their rigging differs from that of a brigantine which has a gaff-rigged mainsail, while a brig has a square mainsail with an additional gaff-rigged spanker behind the mainsail.

Upernavik is a small town in the Avannaata municipality in northwestern Greenland, located on a small island of the same name. With 1,055 inhabitants as of 2017, it is the thirteenth-largest town in Greenland. It contains the Upernavik Museum. It is the northern-most town in Greenland with a population of over 1,000.

After visiting England to fulfill his promise to deliver his report personally to Lady Franklin, he sailed to Havana, Cuba in a vain attempt to recover his health, after being advised to do so by his doctor. He died there on February 16, 1857.

Havana is the capital city, largest city, province, major port, and leading commercial center of Cuba. The city has a population of 2.1 million inhabitants, and it spans a total of 781.58 km2 (301.77 sq mi) – making it the largest city by area, the most populous city, and the fourth largest metropolitan area in the Caribbean region.

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is a country comprising the island of Cuba as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located in the northern Caribbean where the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean meet. It is east of the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico), south of both the U.S. state of Florida and the Bahamas, west of Haiti and north of both Jamaica and the Cayman Islands. Havana is the largest city and capital; other major cities include Santiago de Cuba and Camagüey. The area of the Republic of Cuba is 110,860 square kilometres (42,800 sq mi). The island of Cuba is the largest island in Cuba and in the Caribbean, with an area of 105,006 square kilometres (40,543 sq mi), and the second-most populous after Hispaniola, with over 11 million inhabitants.

His body was brought to New Orleans, and carried by a funeral train to Philadelphia; the train was met at nearly every platform by a memorial delegation, and is said to have been the longest funeral train of the century excepting only Lincoln's.

Honors

Dr. Kane received medals from Congress, the Royal Geographical Society, and the Société de Géographie.

Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1855. [7]

The destroyer USS Kane (DD-235) was named for him, as was a later oceanographic research ship, the USNS Kane (T-AGS-27).

A prestigious masonic lodge, based in New York City, is named after him. [8]

The crater Kane on the Moon was also named for him.

On May 28, 1986, the United States Postal Service issued a 22 cent postage stamp in his honor, depicting his route to the Arctic. [9]

The Anoatok historic home at Kane, Pennsylvania was named to allude to his Arctic adventures.

The Geographical Society of Philadelphia created the Elisha Kent Kane Medal in his honor.

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.