| Name | Name on the Norwegian Map | Position (Informationen in the "Bundesanzeiger") | Named after / Note |

|---|

| Alexander-von-Humboldt-Mountains | Humboldtfjella | 71° 24′–72° S, 11°–12° O | Alexander von Humboldt |

| Humboldt Basin | Humboldtsøkket | Near the eastern border of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Mountains | Alexander von Humboldt |

| Altar | Altaret | 71° 36′ S, 11° 18′ O | distinctive mountain shape |

| Amelang Plateau | Ladfjella | 74° S, 6° 12′–6° 30′ W | Herbert Amelang, 1. Officer of the "Schwabenland“ |

| Am Überlauf (At the Overflow) | Grautrenna | Easterly to the Eckhörner (Corner Horns) | glaciated pass |

| Barkley Mountains | Barkleyfjella | 72° 48′ S, 1° 30′–0° 48′ O | Erich Barkley (1912–1944), biologist |

| Bastion | Bastionen | 71° 18′ S, 13° 36′ O | |

| Bludau Mountains | Hallgrenskarvet und Heksegryta | Part Iof a 150 km mountain range 72° 42′ S, 3° 30′ W und 74° S, 5° W | Josef Bludau (1889–1967), ships surgeon |

| Mount Bolle | | 72° 18′ S, 6° 30′ O | Herbert Bolle, Deutsche Lufthansa, foreman of the aircraft assemblers |

| Boreas | Boreas | | Dornier Wal D-AGAT „Boreas“ |

| Brandt Mountain | | 72° 13′ S, 1° 0′ O | Emil Brandt (* 1900), Sailor, saved an expedition member from drowning |

| Mount Bruns | | 72° 05′ S, 1° 0′ O | Herbert Bruns (* 1908), electrical engineer of the expedition ship |

| Buddenbrock Range | | 71° 42′ S, 6° O | Friedrich Freiherr von Buddenbrock, Operations Manager of Atlantic Flights at Deutsche Lufthansa |

| Bundermann Range | Grytøyrfjellet | 71° 48′–72° S, 3° 24′ O | Max Bundermann (* 1904), aerial photographer |

| Conrad Mountains | Conradfjella | 71° 42′–72° 18′ S, 10° 30′ O | Fritz Conrad |

| Dallmann Mountains | Dallmannfjellet | 71° 42′–72° S, closely west 11° O | Eduard Dallmann |

| Drygalski Mountains | Drygalskifjella | 71° 6′–71° 48′ S, 7° 6′–9° 30′ O [17] | Erich von Drygalski |

| Eckhörner (Corner Horns) | Hjørnehorna | North end of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Gebirges | markante Bergform |

| Filchner Mountains | Filchnerfjella | 71° 6′–71° 48′ S, 7° 6′–9° 30′ O [17] | Wilhelm Filchner |

| Gablenz-Ridge | | 72°–72° 18′ S, 5° O | Carl August von Gablenz |

| Gburek Peaks | Gburektoppane | 72° 42′ S, 0° 48′–1° 10′ W | Leo Gburek (1910–1941), geomagnetist |

| Geßner Peak | Gessnertind | 71° 54′ S, 6° 54′ O | Wilhelm Geßner (1890–1945), Director of Hansa Luftbild |

| Gneiskopf Peak | Gneisskolten | 71° 54′ S, 12° 12′ O | prominent peak |

| Gockel-Ridge | Vorrkulten | 73° 12′ S, 0° 12′ W | Wilhelm Gockel, meteorologist of the expedition |

| Graue Hörner (Grey Horns) | Gråhorna | Southern corner of the Petermann mountain range | |

| Gruber Mountains | Slokstallen und Petrellfjellet | 72° S, 4° O | Erich Gruber (1912–1940), radio operator on D-AGAT „Boreas“ |

| Habermehl Peak | Habermehltoppen | Westernly to the Geßnerpeak | Richard Habermehl, head of the Reich Weather Service |

| Mount Hädrich | | 71° 57′ S, 6° 12′ O | Willy Hädrich, Authorized officer at Deutsche Lufthansa, responsible for the accounting of the expedition |

| Mount Hedden | | 72° 8′ S, 1° 10′ O | Karl Hedden, Sailor, saved an expedition member from drowning |

| Herrmann Mountains | | 73° S, 0°–1° O | Ernst Herrmann, geologist of the expedition |

| In der Schüssel (In the Bowl) | Grautfatet | in the North of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Gebirges | glaciated valley |

| Johannes Müller Ridge | Müllerkammen | | Johannes Müller († 1941), Participant in the 2nd German South Polar Expedition in 1911/12, Head of the Nautical Department of the North German Lloyd |

| Kaye Peak | Langfloget | 72° 30′ S, 4° 48′ O | Georg Kaye, Naval architect, looked after the ships of Lufthansa |

| Kleinschmidt Peak | Enden | Part of a 150 km long ridge between 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and 74° S, 5° W | Ernst Kleinschmidt, German Maritime Observatory |

| Kottas Mountains | Milorgfjella | 74° 6′–74° 18′ S, 8° 12′–9° W | Alfred Kottas, Captain of the "Schwabenland" |

| Kraul Mountains | Vestfjella | | Otto Kraul, ice pilot |

| Krüger Mountains | Kvitskarvet | 73° 6′ S, 1° 18′ O | Walter Krüger, meteorologist of the expedition |

| Kubus | Kubus | 72° 24′ S, 7° 30′ O | distinctive mountain shape |

| Kurze Mountain Range | Kurzefjella | 72° 6′–72° 30′ S, 9° 30′–10° O | Friedrich Kurze,Vice Admiral, Head of the Nautical Department of the Naval High Command |

| Lange-Plateau | | 71° 58′ S, 0° 25′ O | Heinz Lange (1908–1943), meteorlogical assistant |

| Loesener Plateau | Skorvetangen, Hamarskorvene und Kvithamaren | 72° S, 4° 18′ O | Kurt Loesener, airplane mechanic of D-AGAT „Boreas“ |

| Lose Plateau | Lausflæet | | distinctive mountain shape |

| Luz Ridge | | 72°–72° 18′ S, 5° 30′ O | Martin Luz, commercial director at the German Lufthansa |

| Mayr Mountain Range | Jutulsessen | 72°–72° 18′ S, 3° 24′ O | Rudolf Mayr, Pilot of D-ALOX „Passat“ |

| Matterhorn | Ulvetanna | highest peak in den Drygalski-Mountains | distinctive mountain shape |

| Mentzel Mountains | Mentzelfjellet | 71° 18′ S, 13° 42′ O | Rudolf Mentzel |

| Mühlig-Hofmann Mountains | Mühlig-Hofmannfjella | 71° 48′–72° 36′ S, 3° O | Albert Mühlig-Hofmann |

| Neumayer steep face | Neumayerskarvet | | Georg von Neumayer |

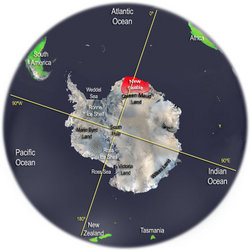

| New Swabia | | | Expeditionship „Schwabenland“ |

| Northwestern Island | Nordvestøya | Northend of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Gebirges | island-like nunatak group |

| Eastern Hochfeld | Austre Høgskeidet | between the southern and central sections of the Petermann range | Ice tongue |

| Obersee (Upper Lake) | Øvresjøen | 71° 12′ S, 13° 42′ O | frozen lake |

| Passat | Passat | | Donier Wal D-ALOX |

| Paulsen Mountains | Brattskarvet, Vendeholten und Vendehø | 72° 24′ S, 1° 30′ O | Karl-Heinz Paulsen, oceanographer of the expedition |

| Payer Mountain group | Payerfjella | 72° 0′ S, 14° 42′ O | Julius von Payer |

| Penck Trough | Pencksøkket | | Albrecht Penck |

| Petermann Range | Petermannkjeda | Between the Alexander-Humboldt-Mountains and the „zentralen Wohlthatmassiv“ [=Otto-von-Gruber-Mountains] on 71°18′–72°9′ S | August Petermann |

| Preuschoff Ridge | Hochlinfjellet | 72° 18′–72° 30′ S, 4° 30′ O | Franz Preuschoff, airplane Mechanic of D-ALOX „Passat“ |

| Regula Mountain Range | Regulakjeda | | Herbert Regula (1910–1980), I. Meteorologist of the expedition |

| Ritscherpeak | Ritschertind | 71° 24′ S, 13° 24′ O | Alfred Ritscher |

| Ritscher Upland | Ritscherflya | | Alfred Ritscher |

| Mount Röbke | Isbrynet | | Karl-Heinz Röbke (* 1909), II. Officer on the „Schwabenland“ |

| Mount Ruhnke | Festninga | 72° 30′ S, 4° O | Herbert Ruhnke (1904–1944), Radio operator on D-ALOX „Passat“ |

| Sauter Mountain bar | Terningskarvet | 72° 36′ S, 3° 18′ O | Siegfried Sauter, aerial photographer |

| Schirmacher Ponds [18] | Schirmacher Oasis | 70° 40′ S, 11° 40′ O | Richardheinrich Schirmacher, Pilot of D-AGAT „Boreas“ |

| Schneider-Riegel | | 73° 42′ S, 3° 18′ W | Hans Schneider, Head of the Sea-Flight Department of the German Maritime Observatory and Professor of Meteorology |

| Schubertpeak | Høgfonna und Ovbratten | Part of a 150 km long ridge between 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W und 74° S, 5° W | Otto von Schubert, Head of the Nautical Department of the German Maritime Observatory |

| Schulz Heights | Lagfjella | 73° 42′ S, 7° 36′ W | Robert Schulz, II. Engineer on the „Schwabenland“ |

| Schicht Mountains | Sjiktberga | 71° 24′ S, 13° 12′ O | |

| Schwarze Hörner (Black horns) | Svarthorna | southern corner of the northern part of the Petermann range | distinctive mountain range |

| See Kopf (Sea-Head) | Sjøhausen | 71° 12′ S, 13° 48′ O | distinctive mountain |

| Seilkopf Mountains | Nälegga | Part of a 150 km long ridge between 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and° S, 5° W | Heinrich Seilkopf, Head of the Sea-Flight Department of the German Maritime Observatory and Professor of Meteorology |

| Sphinxkopf Peak | Sfinksskolten | On the north end of the Petermann range | distinctive mountain |

| Spieß Peak | Huldreslottet | Part of a 150 km long ridge between. 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and 74° S, 5° W | Admiral Fritz Spieß, commander of the research vessel Meteor |

| Stein Peaks | Straumsnutane | | Willy Stein, Boatswain of the „Schwabenland“ |

| Todt Mountain bar | Todtskota | 71° 18′ S, 14° 18′ O | Herbert Todt, Assistent of the expeditionleader |

| Uhligpeak | Uhligberga | Part of a 150 km long ridge between72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and 74° S, 5° W | Karl Uhlig, Leading Engineer of the „Schwabenland“ |

| Lake Untersee | Nedresjøen | 71° 18′ S, 13° 30′ O | frozen lake |

| Vorposten Peak | Forposten | 71° 24′ S, 15° 48′ O | remote nunatak |

| Western Hochfeld | Vestre Høgskeidet | | glaciated plain |

| Weyprecht Mountains | Weyprechtfjella | 72° 0′ S, 13° 30′ O | Carl Weyprecht |

| Wegener Inland Ice | Wegenerisen | | Alfred Wegener |

| Wittepeaks | Marsteinen, Valken, Krylen und Knotten | | Dietrich Witte, engine attendant of the "Schwabenland“ |

| Wohlthat Mountain Range | Wohlthatmassivet | | Helmuth Wohlthat |

| Mount Zimmermann | Zimmermannfjellet | 71° 18′ S, 13° 24′ O | Carl Zimmermann, Vice President of the German Research Foundation |

| Zuckerhut (sugar loaf) | Sukkertoppen | 71° 24′ S, 13° 30′ O | distinctive mountain shape |

| Zwiesel Mountain | Zwieselhøgda | On the southern ends of the Petermann range | |