History

The first documented Kurdish film produced in Soviet Armenia was a 1927 silent film called Zarê , directed by Hamo Beknazarian. Set in 1915, the film depicts a romance between a young Yezidi couple, the shepherd Saydo and the titular Zare. In line with the 1920s ideologies, the film portrays how the Tsar administration used the ignorance of the Kurds to exploit from them with the help of the religious clerics and leaders. Krder-ezidner(Kurds-Yezidis), another black-and-white milestone silent film about Yezidi Kurds in Soviet Armenia was released in 1933. Directed by Amasi Martirosyan, it exhibited the establishment of a Kolkhoz in a Kurdish village. [2]

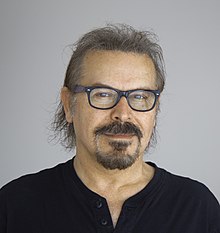

One of the founding fathers of Kurdish cinema is Yilmaz Güney, who is admired by Kurdish filmmakers for his ability to portray Kurdish cultures in his films, notably Sürü and Yol , despite restrictions levied against him by the Turkish Government. [3] Güney began making films in the 1950s. He won the Palme d`Or at the Cannes Film Festival for his 1982 film Yol – The Road. [4] [5]

In the 1990s, Kurdish cinema culture received support from the newly founded Mesopotamia Cultural Center (MKM). The MKM established a cinema department in which several Kurdish directors made their first movies. [6] In 1995, the Istanbul branch of the MKM organized a cinema workshop. [6]

Yilmaz Güney, Jano Rosebiani, Bahman Qubadi, Shawkat Amin Korky, Mano Khalil, Hisham Zaman, Sahim Omar Kalifa, Bina Qeredaxi and Yüksel Yavuz are among the better known Kurdish directors. Some Kurdish filmmakers like Hiner Saleem live and work outside Kurdistan. [7]

In 1991, a Kurdish film, A Song for Beko by writer-director Nizamettin Ariç, was produced as a German-Armenian production. In 1992, director Ümit Elçi shot Mem û Zîn as a Turkish production. The film Siyabend and Xecê dates back to 1993 and was also produced in Turkey. The number of Kurdish films shot in Iran is growing gradually. Bahman Qubadi, for example, received the Special Mention by the Youth Jury for his film at the Berlinale Turtles Can Fly . [8]

Miraz Bezar's movie Min Dît: The Children of Diyarbakır won awards at the film festivals in San Sebastian, Hamburg, and Ghent. It was the first Kurdish-language movie at a Turkish film festival. It was shown at the Golden Orange Film Festival in Antalya where it won the special jury prize. [9] In the last couple of years in Germany and Switzerland, Kurdish filmmakers in exile who receive public funding from the states they live in, such as NEWA Film Berlin [10] or Frame Film GmbH Bern, for example have created film production companies. [11]

Through the 2000s and 2010s, there was an influx of documentary films filmed throughout Kurdistan. Kurdish filmmakers used documentary films as a tool to educate mainly Western viewers. They have shown their films in film festivals and on social networking sites to bring attention to the past and current events that have, and are, taking place in Kurdistan. [12] Many of these documentaries are shot in cinéma vérité styles, with a small budget and crew. The film Banaz: A Love Story , directed and produced by Deeyah Khan, documents Banaz Mahmod, a 20-year-old Kurdish woman from Mitcham, south London, who was killed in 2006 in a murder orchestrated by her father, uncle, and cousins. [13] It won the 2013 Emmy award for Best International Current Affairs Film. [14]