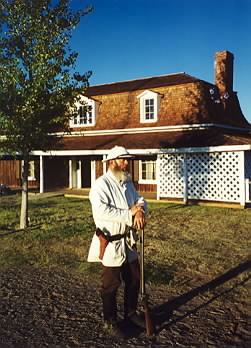

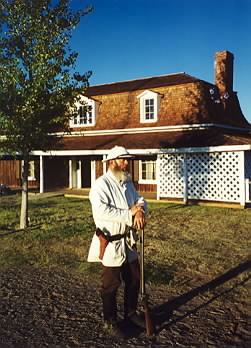

Fort Verde State Historic Park in the town of Camp Verde, Arizona is a small park that attempts to preserve parts of the Apache Wars-era fort as it appeared in the 1880s. The park was established in 1970 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places a year later.

Marycrest College Historic District is located on a bluff overlooking the West End of Davenport, Iowa, United States. The district encompasses the campus of Marycrest College, which was a small, private collegiate institution. The school became Teikyo Marycrest University and finally Marycrest International University after affiliating with a private educational consortium during the 1990s. The school closed in 2002 because of financial shortcomings. The campus has been listed on the Davenport Register of Historic Properties and on the National Register of Historic Places since 2004. At the time of its nomination, the historic district consisted of 13 resources, including six contributing buildings and five non-contributing buildings. Two of the buildings were already individually listed on the National Register.

Farmington, an 18-acre (7.3 ha) historic site in Louisville, Kentucky, was once the center of a hemp plantation owned by John and Lucy Speed. The 14-room, Federal-style brick plantation house was possibly based on a design by Thomas Jefferson and has several Jeffersonian architectural features. As many as 64 African Americans were enslaved by the Speed family at Farmington.

Light's Fort was built in 1742 by Johannes Peter Leicht [John Light] (1682-1758). Light's Fort is the oldest standing building of any kind in the county and city of Lebanon, Pennsylvania. John Light, an immigrant, purchased the land on December 29, 1738, from Caspar Wistar, and wife, Katherine, of the City of Philadelphia, Brass Button Maker, for 82 pounds and 4 shillings. Light's Fort was built in 1742 on a tract of land, which was situated on a branch of the Quittapahilla Creek in Lancaster County at North 11th and Maple Streets. It contained 274 acres including an allowance of 6% for roads together with woods, water courses, etc.

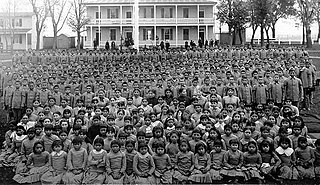

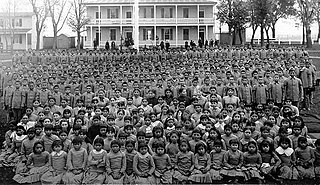

Fort Totten State Historic Site is a historic fort that sits on the shores of Devils Lake near Fort Totten, North Dakota. During its 13 years of operation as a fort, Fort Totten was used during the American Indian wars to enforce the peace among local Native American tribes and to protect transportation routes. After its closing in 1890, it operated until 1959 as a Native American boarding school, called the Fort Totten Indian Industrial School. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971; in its nomination form, the State Historical Society of North Dakota called it "one of the best preserved military posts... in the Trans-Mississippi West for the Indian Wars period".

Bathhouse Row is a collection of bathhouses, associated buildings, and gardens located at Hot Springs National Park in the city of Hot Springs, Arkansas. The bathhouses were included in 1832 when the Federal Government took over four parcels of land to preserve 47 natural hot springs, their mineral waters which lack the sulphur odor of most hot springs, and their area of origin on the lower slopes of Hot Springs Mountain.

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into European American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion. At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations, especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid religious orders to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools based on the assimilation model. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools.

The Le Roy House and Union Free School are located on East Main Street in Le Roy, New York, United States. The house is a stucco-faced stone building in the Greek Revival architectural style. It was originally a land office, expanded in two stages during the 19th century by its builder, Jacob Le Roy, an early settler for whom the village is named. In the rear of the property is the village's first schoolhouse, a stone building from the end of the 19th century.

The Stewart Indian School (1890–1980) was an Indian school southeast of Carson City, Nevada that is noted for the masonry work of colored native stone used by student apprentices to build the vernacular-style buildings. The school, part of the Native American boarding schools project, was the only off-reservation boarding school in Nevada. Funding for the school was obtained by Nevada's first senator, William M. Stewart, and it was named in his honor when it opened on December 17, 1890. It has also been known as Stewart Institute, Carson Industrial School, and Carson Indian School.

St. Joseph's Indian Normal School is a former school for American Indians in Rensselaer, Indiana. The school building is now known as Drexel Hall and part of the Saint Joseph's College campus. Boarding schools were believed to be the best way to assimilate them into the white culture. The school lasted from 1888 to 1896 and was funded by the U.S. government and Catholic missionaries. It was believed that this was the best way to "civilize" Native Americans and the western territories. Established by the Catholic Indian Missions with funding from St. Katharine Drexel, the school taught 60 Indian children. The Society of Precious Blood operated the school during its years of operation. The students were all boys. When the Indian School was closed, the building was named Drexel Hall. It is one of the first structures of Saint Joseph's College.

The Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), headquartered in the Main Interior Building in Washington, D.C., and formerly known as the Office of Indian Education Programs (OIEP), is a division of the U.S. Department of the Interior under the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs. It is responsible for the line direction and management of all BIE education functions, including the formation of policies and procedures, the supervision of all program activities, and the approval of the expenditure of funds appropriated for BIE education functions.

The Community Building, also known as Community Hall, Boll's Store, or Boll's Community Center, is a building in Princeton, Iowa, United States. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008.

Heinrich Zeller House, also known as Fort Zeller and Zeller's Fort, is a historic 1+1⁄2-story building that has served as a fort, block house and residence. The historic structure is located in Millcreek Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania.

The Wallowa County Courthouse is the seat of government for Wallowa County in northeastern Oregon. The courthouse is located in Enterprise, Oregon. It was built in 1909–1910 using locally quarried stone. It is a massive High Victorian structure built of local Bowlby stone. The courthouse was listed on National Register of Historic Places in 2000. Today, the courthouse still houses Wallowa County government offices.

The Hopewell High School Complex, also known as James E. Mallonee Middle School, is a historic former school campus located at 1201 City Point Road in Hopewell, Virginia, United States. Contributing properties in the complex include the original school building, athletic field, club house, concession stand, press box, Home Economics Cottage, gymnasium and Science and Library Building. There are two non-contributing structures on the property.

The Pawnee Agency and Boarding School District lies east of the city of Pawnee in Pawnee County, Oklahoma. Other names are: Pawnee Indian Agency, Pawnee Indian School and Pawnee Indian Boarding School. The District occupies approximately 29 acres (12 ha) of the Pawnee Tribal Reserve, a 726 acres (294 ha) tract that is owned by the Pawnee tribe. Black Bear Creek divides the District from the town. The Pawnee Agency was established as a post office on May 4, 1876.

Hemmant State School is a heritage-listed state school at 56 Hemmant-Tingalpa Road, Hemmant, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. It was built from 1876 to 1930s. Its architects included Francis Drummond Greville Stanley. It was also known as Bulimba Creek School and Doughboy Creek Mixed School. On its grounds is the historic house Dumbarton, also known as Ashcroft House and Gibson House. The original Hemmant State School closed at the end of 2010, and in 2012 was replaced by the Hemmant Flexible Learning Centre, a new school targeted at students disengaged from mainstream education. The school buildings and structures were added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 4 September 2003.

Fort Apache Historic Park is a tribal historic park of the White Mountain Apache, located at the former site of Fort Apache on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation. The park interprets the rich and troubled history of relations between the Apache and other Native American tribes at the fort, which was converted into a Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school after its military use ended. The park, which covers 288 acres (117 ha) of the former fort and school, as well as a nearby military cemetery, form the National Historic Landmark Fort Apache and Theodore Roosevelt School historic district.

Fort Spokane was a frontier outpost in the northwest United States, located in Lincoln County, Washington, approximately fifty miles (80 km) west-northwest of Spokane. At the confluence of the Columbia and Spokane rivers, the U.S. Army post was used to separate the Colville and Spokane tribes on their reservations from the newly established city of Spokane. The fort was last used in 1929 and was later incorporated into the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Hospital Reservation Historic District is located between Radio Station and Officers Row Historic Districts and east of the Marine Reservation Historic District of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Washington. Established in 1909, it reached its maximum development in 1942. The following structures no longer remain:

- ‘"Main Hospital Building"’ (1911,1924): a Neo-Classical, two story with basement brick complex.

- "’Recreation building"’ (1920): two story vernacular wood frame structure with basement; to the west was a yard cemetery, which was relocated to the Presidio in San Francisco, California.

- "’Navy Female Nurse Corps Quarters"’ (1921) was a two-story wood frame structure.

- "’Three Isolation Buildings"’ (1915) were located of the main hospital. Along with other buildings constructed here, all but one isolation building were eventually connected to the main hospital building.