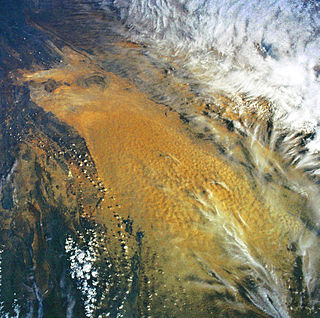

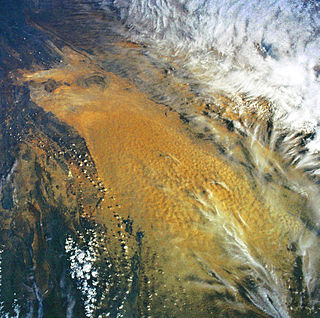

The Taklamakan Desert is a desert in northwest China's Xinjiang region. Located inside the Tarim Basin in Southern Xinjiang, it is bounded by the Kunlun Mountains to the south, the Pamir Mountains to the west, the Tian Shan range to the north, and the Gobi Desert to the east.

Sven Anders Hedin, KNO1kl RVO, was a Swedish geographer, topographer, explorer, photographer, travel writer and illustrator of his own works. During four expeditions to Central Asia, he made the Transhimalaya known in the West and located sources of the Brahmaputra, Indus and Sutlej Rivers. He also mapped lake Lop Nur, and the remains of cities, grave sites and the Great Wall of China in the deserts of the Tarim Basin. In his book Från pol till pol, Hedin describes a journey through Asia and Europe between the late 1880s and the early 1900s. While traveling, Hedin visited Turkey, the Caucasus, Tehran, Iraq, lands of the Kyrgyz people and the Russian Far East, India, China and Japan. The posthumous publication of his Central Asia Atlas marked the conclusion of his life's work.

The Tarim River, known in Sanskrit as the Śītā, is an endorheic river in Xinjiang, China. It is the principal river of the Tarim Basin, a desert region of Central Asia between the Tian Shan and Kunlun Mountains. The river historically terminated at Lop Nur, but today reaches no further than Taitema Lake before drying out.

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Xinjiang, Northwestern China occupying an area of about 888,000 km2 (343,000 sq mi) and one of the largest basins in Northwest China. Located in China's Xinjiang region, it is sometimes used synonymously to refer to the southern half of the province, that is, Southern Xinjiang or Nanjiang, as opposed to the northern half of the province known as Dzungaria or Beijiang. Its northern boundary is the Tian Shan mountain range and its southern boundary is the Kunlun Mountains on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. The Taklamakan Desert dominates much of the basin. The historical Uyghur name for the Tarim Basin is Altishahr, which means 'six cities' in Uyghur. The region was also called Little Bukhara or Little Bukharia.

The Lop Desert, or the Lop Depression, is a desert extending from Korla eastwards along the foot of the Kuruk-tagh to the former terminal Tarim Basin in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. It is an almost perfectly flat expanse with no topographic relief. Lake Bosten in the northwest lies at an altitude of 1,030 to 1,040 m, while the Lop Nur in the southeast is only 250 m lower.

Shanshan was a kingdom located at the north-eastern end of the Taklamakan Desert near the great, but now mostly dry, salt lake known as Lop Nur.

Loulan, also known as Kroraïna in native Gandhari documents or Krorän in later Uyghur, was an ancient kingdom based around an important oasis city along the Silk Road already known in the 2nd century BCE on the northeastern edge of the Lop Desert. The term Loulan is the Chinese transcription of the native name Kroraïna and is used to refer to the city near the brackish desert lake Lop Nur as well as the kingdom.

The Tarim mummies are a series of mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin in present-day Xinjiang, China, which date from 1800 BCE to the first centuries BCE, with a new group of individuals recently dated to between c. 2100 and 1700 BCE. The Tarim population to which the earliest mummies belonged was agropastoral, and they lived c. 2000 BCE in what was formerly a freshwater environment, which has now become desertified.

Taitema Lake is an endorheic lake in Ruoqiang County, Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, southeast of the Tarim Basin, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People's Republic of China. It is located in the northern part of Ruoqiang County, and is one of the three main depressions of that area, the other two being Karakoshun Lake (喀拉库顺湖) and Lop Nur.

The Tarim Basin deciduous forests and steppe is a temperate broadleaf and mixed forests ecoregion in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of western China. The ecoregion includes deciduous riparian forests and steppes sustained by the region's rivers in an otherwise arid region.

The Niya ruins, is an archaeological site located about 115 km (71 mi) north of modern Niya Town on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin in modern-day Xinjiang, China. The ancient site was known in its native language as Caḍ́ota, and in Chinese during the Han dynasty as Jingjue. Numerous ancient archaeological artifacts have been uncovered at the site.

Miran or Mirān is a former city that existed until the 1st millennium, on the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, China. Located at an oasis, where the Lop Nur desert meets the Altun Shan mountains, Miran was once a major point on the Silk Road.

Charklik or Charkhlik is an archaeological site named after the town of Charkhlik (Qakilik), in Ruoqiang (Qakilik) County, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Together with the nearby Miran site, they correspond to two ancient capitals of Shanshan, Wuni and Yixun. However, it is as yet unclear which site correspond to which capital.

The Qiemo River, also called the Cherchen or Qarqan River, runs across the Tarim Basin in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. It feeds into the Lop Nor salty marshes and the Taitema Lake.

The Xiaohe Cemetery, also known as Ördek's Necropolis, is a Bronze Age site located in the west of Lop Nur, in Xinjiang, Western China. It contains about 330 tombs, about 160 of which were looted by grave robbers before archaeological research could be carried out.

The Beauty of Loulan (楼兰美女), also Beauty of Krorän or Loulan Beauty, is the preserved dead body of a woman who lived around 1800 BC in the Xinjiang region of China. Due to her excellent state of conservation, she is one of the most famous Tarim mummies.

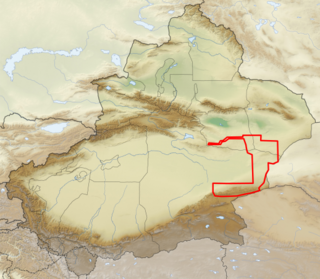

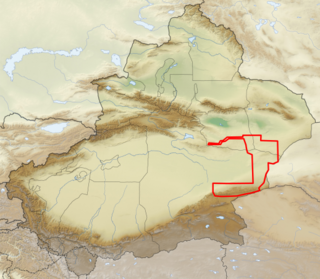

Lop Nur Wild Camel National Nature Reserve protects one of the three remaining habitats of the Wild Bactrian camel, a critically endangered species. The reserve stretches around the north, east, and south of Lop Nur, a dry lake in a desert known as the "Sea of Death", and one of the most arid regions in the world. The reserve was established in 1986 by Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and has been modified over the years. The reserve is under pressure from new roads in the area, development of mining interests, and illegal hunting.

The Sino-Swedish Expedition was a bilateral Chinese-Swedish expedition, led by Sven Hedin, which carried out scientific research in north and northwest China, 1927–1935.

The Princess of Xiaohe or Little River Princess was found in 2003 at Xiaohe Cemetery in Lop Nur, Xinjiang. She is one of the Tarim mummies, and is known as M11 for the tomb she was found in. Buried approximately 3,800 years ago, she has European and Siberian genes and has white skin and red hair. She is unusually well preserved, with clothes, hair, and eyelashes still intact.

Karakoshun Lake was an inland lake located in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China, which is now dry.