This article may be too technical for most readers to understand.(December 2023) |

The Lorenz system is a set of three ordinary differential equations, first developed by the meteorologist Edward Lorenz while studying atmospheric convection. It is a classic example of a system that can exhibit chaotic behavior, meaning its output can be highly sensitive to small changes in its starting conditions.

Contents

- Overview

- Analysis

- Connection to the Tent map

- Simulations

- Julia simulation

- Maple simulation

- Maxima simulation

- MATLAB simulation

- Mathematica simulation

- R simulation

- SageMath simulation

- Applications

- Model for atmospheric convection

- Model for the nature of chaos and order in the atmosphere

- Resolution of Smale's 14th problem

- Gallery

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

- External links

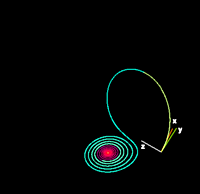

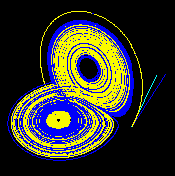

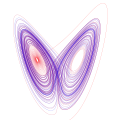

For certain values of its parameters, the system's solutions form a complex, looping pattern known as the Lorenz attractor. The shape of this attractor, when graphed, is famously said to resemble a butterfly. The system's extreme sensitivity to initial conditions gave rise to the popular concept of the butterfly effect—the idea that a small event, like the flap of a butterfly's wings, could ultimately alter large-scale weather patterns. While the system is deterministic—its future behavior is fully determined by its initial conditions—its chaotic nature makes long-term prediction practically impossible.

The behavior of the system depends on the choice of parameters. For some ranges of parameters, the system is predictable: trajectories settle into fixed points or simple periodic orbits, making the long-term behavior easy to describe. For example, when ρ < 1, all solutions converge to the origin, and for certain moderate values of ρ, σ, and β, solutions converge to symmetric steady states.

In contrast, for other parameter ranges, the system becomes chaotic. With the well-known parameters σ = 10, ρ = 28, and β = 8/3, the solutions never settle down but instead trace out the butterfly-shaped Lorenz attractor. In this regime, small differences in initial conditions grow exponentially.