Related Research Articles

Rapa Nui or Rapanui, also known as Pascuan or Pascuense, is an Eastern Polynesian language of the Austronesian language family. It is spoken on the island of Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island.

Vaeakau-Taumako is a Polynesian language spoken in some of the Reef Islands as well as in the Taumako Islands in the Temotu province of the Solomon Islands.

Taba is a Malayo-Polynesian language of the South Halmahera–West New Guinea group. It is spoken mostly on the islands of Makian, Kayoa and southern Halmahera in North Maluku province of Indonesia by about 20,000 people.

The Nafsan language, also known as South Efate or Erakor, is a Southern Oceanic language spoken on the island of Efate in central Vanuatu. As of 2005, there are approximately 6,000 speakers who live in coastal villages from Pango to Eton. The language's grammar has been studied by Nick Thieberger, who has produced a book of stories and a dictionary of the language.

Kambera, also known as East Sumbanese, is a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken in the Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia. Kambera is a member of Bima-Sumba subgrouping within Central Malayo-Polynesian inside Malayo-Polynesian. The island of Sumba, located in Eastern Indonesia, has an area of 12,297 km2. The name Kambera comes from a traditional region which is close to a town in Waingapu. Because of export trades which concentrated in Waingapu in the 19th century, the language of the Kambera region has become the bridging language in eastern Sumba.

Tamambo, or Malo, is an Oceanic language spoken by 4,000 people on Malo and nearby islands in Vanuatu.

Adzera is an Austronesian language spoken by about 30,000 people in Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea.

Apurinã, or Ipurina, is a Southern Maipurean language spoken by the Apurinã people of the Amazon basin. It has an active–stative syntax. Apurinã is a Portuguese word used to describe the Popikariwakori people and their language. Apurinã indigenous communities are predominantly found along the Purus River, in the Northwestern Amazon region in Brazil, in the Amazonas state. Its population is currently spread over twenty-seven different indigenous lands along the Purus River. with an estimated total population of 9,500 people. It is predicted, however, that fewer than 30% of the Apurinã population can speak the language fluently. A definite number of speakers cannot be firmly determined because of the regional scattered presence of its people. The spread of Apurinã speakers to different regions was initially caused by conflict or disease, which has consequently led natives to lose the ability to speak the language for lack of practice and also because of interactions with other communities.

Apma is the language of central Pentecost island in Vanuatu. Apma is an Oceanic language. Within Vanuatu it sits between North Vanuatu and Central Vanuatu languages, and combines features of both groups.

Numbami is an Austronesian language spoken by about 200 people with ties to a single village in Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. It is spoken in Siboma village, Paiawa ward, Morobe Rural LLG.

Hoava is an Oceanic language spoken by 1000–1500 people on New Georgia Island, Solomon Islands. Speakers of Hoava are multilingual and usually also speak Roviana, Marovo, Solomon Islands Pijin, English.

Tuparí is an indigenous language of Brazil. It is one of six Tupari languages of the Tupian language family. The Tuparí language, and its people, is located predominantly within the state of Rondônia, though speakers are also present in the state of Acre on the Terra Indıgena Rio Branco. There are roughly 350 speakers of this language, with the total number of members of this ethnic group being around 600.

Mavea is an Oceanic language spoken on Mavea Island in Vanuatu, off the eastern coast of Espiritu Santo. It belongs to the North–Central Vanuatu linkage of Southern Oceanic. The total population of the island is approximately 172, with only 34 fluent speakers of the Mavea language reported in 2008.

Mekeo is a language spoken in Papua New Guinea and had 19,000 speakers in 2003. It is an Oceanic language of the Papuan Tip Linkage. The two major villages that the language is spoken in are located in the Central Province of Papua New Guinea. These are named Ongofoina and Inauaisa. The language is also broken up into four dialects: East Mekeo; North West Mekeo; West Mekeo and North Mekeo. The standard dialect is East Mekeo. This main dialect is addressed throughout the article. In addition, there are at least two Mekeo-based pidgins.

Tawala is an Oceanic language of the Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. It is spoken by 20,000 people who live in hamlets and small villages on the East Cape peninsula, on the shores of Milne Bay and on areas of the islands of Sideia and Basilaki. There are approximately 40 main centres of population each speaking the same dialect, although through the process of colonisation some centres have gained more prominence than others.

The Sabanê language is one of the three major groups of languages spoken in the Nambikwara family. The groups of people who speak this language were located in the extreme north of the Nambikwara territory in the Rondônia and Mato Grosso states of western Brazil, between the Tenente Marques River and Juruena River. Today, most members of the group are found in the Pyreneus de Souza Indigenous Territory in the state of Rondonia.

Tamashek or Tamasheq is a variety of Tuareg, a Berber macro-language widely spoken by nomadic tribes across North Africa in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Tamasheq is one of the three main varieties of Tuareg, the others being Tamajaq and Tamahaq.

Wamesa is an Austronesian language of Indonesian New Guinea, spoken across the neck of the Doberai Peninsula or Bird's Head. There are currently 5,000–8,000 speakers. While it was historically used as a lingua franca, it is currently considered an under-documented, endangered language. This means that fewer and fewer children have an active command of Wamesa. Instead, Papuan Malay has become increasingly dominant in the area.

Neverver (Nevwervwer), also known as Lingarak, is an Oceanic language. Neverver is spoken in Malampa Province, in central Malekula, Vanuatu. The names of the villages on Malekula Island where Neverver is spoken are Lingarakh and Limap.

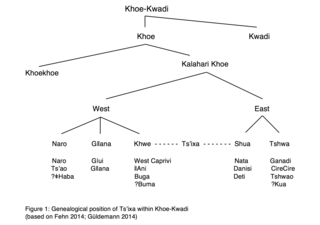

Tsʼixa is a critically endangered African language that belongs to the Kalahari Khoe branch of the Khoe-Kwadi language family. The Tsʼixa speech community consists of approximately 200 speakers who live in Botswana on the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta, in the small village of Mababe. They are a foraging society that consists of the ethnically diverse groups commonly subsumed under the names "San", "Bushmen" or "Basarwa". The most common term of self-reference within the community is Xuukhoe or 'people left behind', a rather broad ethnonym roughly equaling San, which is also used by Khwe-speakers in Botswana. Although the affiliation of Tsʼixa within the Khalari Khoe branch, as well as the genetic classification of the Khoisan languages in general, is still unclear, the Khoisan language scholar Tom Güldemann posits in a 2014 article the following genealogical relationships within Khoe-Kwadi, and argues for the status of Tsʼixa as a language in its own right. The language tree to the right presents a possible classification of Tsʼixa within Khoe-Kwadi: