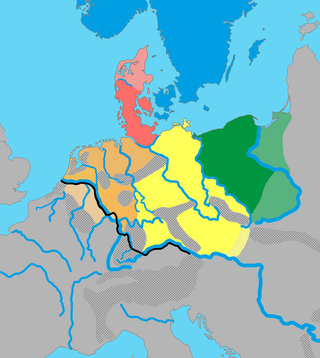

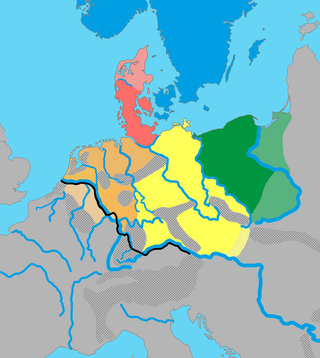

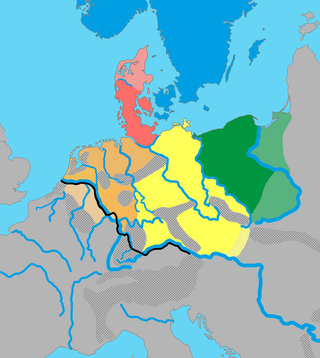

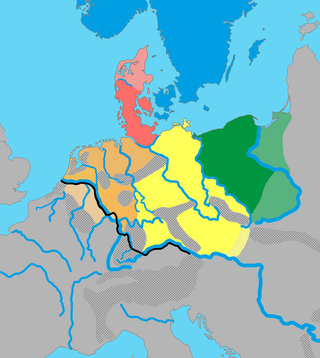

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who once occupied Northwestern and Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and early medieval Germanic languages and are thus equated at least approximately with Germanic-speaking peoples, although different academic disciplines have their own definitions of what makes someone or something "Germanic". The Romans called the area in North-Central Europe in which the Germanic peoples lived Germania. According to its largest definition it stretched between the Vistula in the east and Rhine in the west, and from southern Scandinavia to the upper Danube. In discussions of the Roman period, the Germanic peoples are sometimes referred to as Germani or ancient Germans, although many scholars consider the second term problematic since it suggests identity with present-day Germans. The very concept of "Germanic peoples" has become the subject of controversy among contemporary scholars. Some scholars call for its total abandonment as a modern construct since lumping "Germanic peoples" together implies a common group identity for which there is little evidence. Other scholars have defended the term's continued use and argue that a common Germanic language allows one to speak of "Germanic peoples", regardless of whether these ancient and medieval peoples saw themselves as having a common identity. While several historians and archaeologists continue to use the term "Germanic peoples" to refer to historical people groups from the 1st to 4th centuries CE, the term is no longer used by most historians and archaeologists for the period around the Fall of the Roman Empire and the Early Middle Ages.

The Irminones, also referred to as Herminones or Hermiones, were a large group of early Germanic tribes settling in the Elbe watershed and by the first century AD expanding into Bavaria, Swabia, and Bohemia. Notably this included the large sub-group of the Suevi, that itself contained many different tribal groups, but the Irminones also included for example the Chatti.

In Norse mythology, Ymir, also called Aurgelmir, Brimir, or Bláinn, is the ancestor of all jötnar. Ymir is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional material, in the Prose Edda, written by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century, and in the poetry of skalds. Taken together, several stanzas from four poems collected in the Poetic Edda refer to Ymir as a primeval being who was born from atter, yeasty venom that dripped from the icy rivers called the Élivágar, and lived in the grassless void of Ginnungagap. Ymir gave birth to a male and female from his armpits, and his legs together begat a six-headed being. The grandsons of Búri, the gods Odin, Vili and Vé, fashioned the Earth from his flesh, from his blood the ocean, from his bones the mountains, from his hair the trees, from his brains the clouds, from his skull the heavens, and from his eyebrows the middle realm in which mankind lives, Midgard. In addition, one stanza relates that the dwarfs were given life by the gods from Ymir's flesh and blood.

Old Norse Yngvi, Old High German Ing/Ingwi and Old English Ing are names that relate to a theonym which appears to have been the older name for the god Freyr. Proto-Germanic Ingwaz was the legendary ancestor of the Ingaevones, or more accurately Ingvaeones, and is also the reconstructed name of the Elder Futhark rune ᛜ and Anglo-Saxon rune ᛝ, representing ŋ.

Germanic mythology consists of the body of myths native to the Germanic peoples, including Norse mythology, Anglo-Saxon mythology, and Continental Germanic mythology. It was a key element of Germanic paganism.

The Ingaevones were a Germanic cultural group living in the Northern Germania along the North Sea coast in the areas of Jutland, Holstein, and Lower Saxony in classical antiquity. Tribes in this area included the Angles, Chauci, Saxons, and Jutes.

The Istvaeones were a Germanic group of tribes living near the banks of the Rhine during the Roman Empire which reportedly shared a common culture and origin. The Istaevones were contrasted to neighbouring groups, the Ingaevones on the North Sea coast, and the Herminones, living inland of these groups.

The Germania, written by the Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus around 98 AD and originally entitled On the Origin and Situation of the Germans, is a historical and ethnographic work on the Germanic peoples outside the Roman Empire.

According to Tacitus's Germania, Tuisto is the legendary divine ancestor of the Germanic peoples. The figure remains the subject of some scholarly discussion, largely focused upon etymological connections and comparisons to figures in later Germanic mythology.

In Norse mythology, Borr or Burr was the son of Búri. Borr was the husband of Bestla and the father of Odin, Vili and Vé. Borr receives mention in a poem in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional material, and in the Prose Edda, composed in the 13th century by Icelander Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed a variety of theories about the figure.

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, Netherlands, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in Norse paganism, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed Indo-European religion and post-conversion folklore, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by the Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

Gaut is an early Germanic name, from a Proto-Germanic gautaz, which represents a mythical ancestor or national god in the origin myth of the Geats.

The Alcis or Alci were a pair of divine young brothers worshipped by the Naharvali, an ancient Germanic tribe from Central Europe. The Alcis are solely attested by Roman historian and senator Tacitus in his ethnography Germania, written around 98 AD.

The term man and words derived from it can designate any or even all of the human race regardless of their sex or age. In traditional usage, man itself refers to the species or to humanity (mankind) as a whole.

A grove of Fetters is mentioned in the Eddic poem "Helgakviða Hundingsbana II":

In Germanic paganism, Tamfana is a goddess. The destruction of a temple dedicated to the goddess is recorded by Roman senator Tacitus to have occurred during a massacre of the Germanic Marsi by forces led by Roman general Germanicus. Scholars have analyzed the name of the goddess and have advanced theories regarding her role in Germanic paganism.

Elbe Germanic, also called Irminonic or Erminonic, is a term introduced by the German linguist Friedrich Maurer (1898–1984) in his book, Nordgermanen und Alemanen, to describe the unattested proto-language, or dialectal grouping, ancestral to the later Lombardic, Alemannic, Bavarian and Thuringian dialects. During late antiquity and the Middle Ages, its supposed descendants had a profound influence on the neighboring West Central German dialects and, later, in the form of Standard German, on the German language as a whole.

Ganna was a Germanic seeress, of the Semnoni tribe, who succeeded the seeress Veleda as the leader of a Germanic alliance in rebellion against the Roman Empire. She went together with her king Masyus as envoys to Rome to discuss with Roman emperor Domitian himself, and was received with honours, after which she returned home. She is only mentioned by name in the works of Cassius Dio, but she also appears to have provided posterity with select information about the religious practices and the mythology of the early Germanic tribes, through the contemporary Roman historian Tacitus who wrote them down in Germania. Her name may be a reference to her priestly insignia, the wand, or to her spiritual abilities, and she probably taught her craft to Waluburg who would serve as a seeress in Roman Egypt at the First Cataract of the Nile.

In Norse mythology, the sister-wife of Njörðr is the unnamed wife and sister of the god Njörðr, with whom he is described as having had the twin children Freyr and Freyja. This shadowy goddess is attested to in the Poetic Edda poem Lokasenna, recorded in the 13th century by an unknown source, and the Heimskringla book Ynglinga saga, a euhemerized account of the Norse gods composed by Snorri Sturluson also in the 13th century but based on earlier traditional material. The figure receives no further mention in Old Norse texts.

The Indo-European cosmogony refers to the creation myth of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mythology.