Related Research Articles

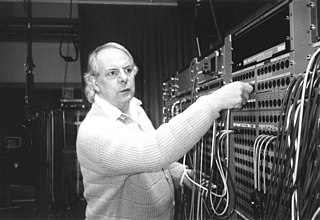

Karlheinz Stockhausen was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groundbreaking work in electronic music, for introducing controlled chance into serial composition, and for musical spatialization.

Licht (Light), subtitled "Die sieben Tage der Woche", is a cycle of seven operas composed by Karlheinz Stockhausen between 1977 and 2003. The composer described the work as an "eternal spiral" because "there is neither end nor beginning to the week." Licht consists of 29 hours of music.

The Helikopter-Streichquartett is one of Karlheinz Stockhausen's best-known pieces, and one of the most complex to perform. It involves a string quartet, four helicopters with pilots, as well as audio and video equipment and technicians. It was first performed and recorded in 1995. Although performable as a self-sufficient piece, it also forms the third scene of the opera Mittwoch aus Licht.

Kontakte ("Contacts") is an electronic music work by Karlheinz Stockhausen, realized in 1958–60 at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) electronic-music studio in Cologne with the assistance of Gottfried Michael Koenig. The score is Nr. 12 in the composer's catalogue of works, and is dedicated to Otto Tomek.

The Klavierstücke constitute a series of nineteen compositions by German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Telemusik is an electronic composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen, and is number 20 in his catalog of works.

Klang —Die 24 Stunden des Tages is a cycle of compositions by Karlheinz Stockhausen, on which he worked from 2004 until his death in 2007. It was intended to consist of 24 chamber-music compositions, each representing one hour of the day, with a different colour systematically assigned to every hour. The cycle was unfinished when the composer died, so that the last three "hours" are lacking. The 21 completed pieces include solos, duos, trios, a septet, and Stockhausen's last entirely electronic composition, Cosmic Pulses. The fourth composition is a theatre piece for a solo percussionist, and there are also two auxiliary compositions which are not part of the main cycle. The completed works bear the work (opus) numbers 81–101.

Suzanne Stephens is an American clarinetist, resident in Germany, described as "an outstanding performer and tireless promoter of the clarinet and basset horn".

Kathinka Pasveer is a Dutch flautist.

Carré (Square) for four orchestras and four choirs (1959–60) is a composition by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, and is Work Number 10 in the composer's catalog of works.

Adieufür Wolfgang Sebastian Meyer is a composition for wind quintet by Karlheinz Stockhausen composed in 1966. It is Number 21 in the composer's catalog of works, and the second of Stockhausen's three wind quintets.

Mittwoch aus Licht is an opera by Karlheinz Stockhausen in a greeting, four scenes, and a farewell. It was the sixth of seven to be composed for the opera cycle Licht: die sieben Tage der Woche, and the last to be staged. It was written between 1995 and 1997, and first staged in 2012.

Mixtur, for orchestra, 4 sine-wave generators, and 4 ring modulators, is an orchestral composition by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, written in 1964, and is Nr. 16 in his catalogue of works. It exists in three versions: the original version for full orchestra, a reduced scoring made in 1967, and a re-notated version of the reduced scoring, made in 2003 and titled Mixtur 2003, Nr. 162⁄3.

Studie I is an electronic music composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen from the year 1953. It lasts 9 minutes 42 seconds and, together with his Studie II, comprises his work number ("opus") 3.

Prozession (Procession), for tamtam, viola, electronium, piano, microphones, filters, and potentiometers, is a composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen, written in 1967. It is Number 23 in the catalogue of the composer’s works.

Cosmic Pulses is the last electronic composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen, and it is number 93 in his catalog of works. Its duration is 32 minutes. The piece has been described as "a sonic roller coaster", "a Copernican asylum", and a "tornado watch".

The Rotary Wind Quintet is a chamber music composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen, the last of his three wind quintets and is Nr. 70½ in his catalogue of works. A performance lasts about 8½ minutes.

Europa-Gruss is a composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen for wind ensemble with optional synthesizers, and is assigned Number 72 in the composer's catalogue of works. It has a duration of about twelve-and-a-half minutes.

Trumpetent is a quartet for four trumpets by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, written in 1995. It is Number 73 in his catalogue of works and one of four independent compositions related to his opera, Mittwoch aus Licht. A performance lasts about 16 minutes.

References

- ↑ Kramer 1988, p. 453.

- ↑ Stockhausen 1963a, p. 189.

- 1 2 Stockhausen 1963b, p. 250.

- ↑ Stockhausen 1963a, p. 200.

- ↑ Dack 1999.

- ↑ Stockhausen 1963a, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Stockhausen and Kohl 1985, p. 25.

- ↑ Stockhausen 2002, pp. xii and xx.

- ↑ Stockhausen 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Stockhausen 2007, p. 3.

- ↑ Albaugh 2004, pp. 1, 7–8.

- ↑ Clarkson 2001.

- ↑ Kramer 1978, p. 178.

- ↑ Kramer 1988, pp. 50–52 and 61–62.

Cited sources

- Albaugh, Michael D. 2004. "Moment Form and Joseph Schwantner's Aftertones of Infinity". DMA diss. Morgantown: West Virginia University. ISBN 0549737960.

- Clarkson, Austin. 2001. "Wolpe, Stefan." The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians , second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan.

- Dack, John. 1999. "Kontakte and Narrativity". eContact! 2, no. 2.

- Kramer, Jonathan. 1978. "Moment Form in Twentieth Century Music" (Subscription access). The Musical Quarterly 64:177–194.

- Kramer, Jonathan. 1988. The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. New York: Schirmer Books; London: Collier Macmillan.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963a. "Momentform: Neue Beziehungen zwischen Aufführungsdauer, Werkdauer und Moment". In his Texte zur Musik, vol. 1, pp. 189–210. Cologne: DuMont Schauberg.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963b. "Erfindung und Entdeckung", in his Texte zur Musik, vol. 1, pp. 222–258. Cologne: DuMont Schauberg.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 2002. Michaelion: 4. Szene vom Mittwoch aus Licht (score). Kürten: Stockhausen-Verlag.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 2006. Stockhausen-Courses Kuerten 2006: Composition Course on KLANG/SOUND, the 24 Hours of the Day: First Hour: ASCENSION for Organ or Synthesizer, Soprano and Tenor, 2004/05, Work No. 81. Kürten: Stockhausen-Verlag.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 2007. Stockhausen-Kurse Kürten 2007: Kompositions-Kurs über KLANG, die 24 Stunden des Tages, Zweite Stunde: FREUDE für 2 Harfen, 2005 / Stockhausen Courses Kuerten 2007: Composition Course on KLANG/SOUND, the 24 Hours of the Day, Second Hour: FREUDE for 2 Harps, 2005, Work no. 82. Kürten: Stockhausen-Verlag.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz, and Jerome Kohl. 1985. "Stockhausen on Opera". Perspectives of New Music 23, no. 2 (Spring): 24–39.