Camelids are members of the biological family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant members of this group are: dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. Camelids are even-toed ungulates classified in the order Artiodactyla, along with species including whales, pigs, deer, cattle, and antelopes.

Toxodon is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the Late Miocene to early Holocene epochs. Toxodon is a member of Notoungulata, an order of extinct South American native ungulates distinct from the two living ungulate orders that had been indigenous to the continent for over 60 million years since the early Cenozoic, prior to the arrival of living ungulates into South America around 2.5 million years ago during the Great American Interchange. Toxodon is a member of the family Toxodontidae, which includes medium to large sized herbivores. Toxodon was one of the largest members of Toxodontidae and Notoungulata, with Toxodon platensis having an estimated body mass of 1,000–1,200 kilograms (2,200–2,600 lb).

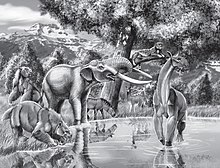

Macrauchenia is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the late Pliocene to the end of the Pleistocene. It is a member of the extinct order Litopterna, a group of South American native ungulates distinct from the two orders which contain all living ungulates which had been present in South America since the early Cenozoic, over 60 million years ago, prior to the arrival of living ungulates in South America around 2.5 million years ago as part of the Great American Interchange. The bodyform of Macrauchenia has been described as similar to a camel, being one of the largest known litopterns, with an estimated body mass of around 1 tonne. The genus gives its name to its family, Macraucheniidae, which like Macrauchenia typically had long necks and three toed feet, as well a retracted nasal region, which in Macrauchenia manifests as the nasal opening being on the top of the skull behind the eye sockets. This has historically been argued to correspond to the presence of a tapir-like proboscis, but some recent authors suggest a moose-like prehensile lip is more likely.

Poebrotherium is an extinct genus of camelid, endemic to North America. They lived from the Eocene to Miocene epochs, 46.3—13.6 mya, existing for approximately 32 million years.

Xenorhinotherium is an extinct genus of macraucheniine macraucheniids, closely related to Macrauchenia of Patagonia. The type species is X. bahiense.

Glossotherium is an extinct genus of large mylodontid ground sloths of the subfamily Mylodontinae. It represents one of the best-known members of the family, along with Mylodon and Paramylodon. Reconstructed animals were between 3 and 4 metres long and possibly weighed up to 1,002.6–1,500 kg. The majority of finds of Glossotherium date from the Middle and Upper Pleistocene, around 300,000 to 10,000 years ago, with a few dating older, as far back Pliocene, about 3.3-3 million years ago. The range included large parts of South America, east of the Andes roughly from latitude 20 to 40 degrees south, leaving out the Amazon Basin in the north. In western South America, finds are also documented north of the equator. The animals largely inhabited the open landscapes of the Pampas and northern savanna regions.

Desmodus draculae is an extinct species of vampire bat that inhabited Central and South America during the Pleistocene, and possibly the early Holocene. It was 30% larger than its living relative the common vampire bat. Fossils and unmineralized subfossils have been found in Argentina, Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Venezuela, Belize, and Bolivia.

The Late Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene saw numerous extinctions of predominantly megafaunal animal species, which resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity across the globe. The extinctions during the Late Pleistocene are differentiated from previous extinctions by the widespread absence of ecological succession to replace these extinct megafaunal species, and the regime shift of previously established faunal relationships and habitats as a consequence. The timing and severity of the extinctions varied by region and are thought to have been driven by varying combinations of human and climatic factors. Human impact on megafauna populations is thought to have been driven by hunting ("overkill"), as well as possibly environmental alteration. The relative importance of human vs climatic factors in the extinctions has been the subject of long-running controversy.

Glyptodon is a genus of glyptodont, an extinct group of large, herbivorous armadillos, that lived from the Pliocene, around 3.2 million years ago, to the early Holocene, around 11,000 years ago, in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Argentina, and Colombia. It is one of, if not the, best known genus of glyptodont. Glyptodon has a long and storied past, being the first named extinct cingulate and the type genus of the subfamily Glyptodontinae. Fossils of Glyptodon have been recorded as early as 1814 from Pleistocene aged deposits from Uruguay, though many were incorrectly referred to the ground sloth Megatherium by early paleontologists.

Hemiauchenia is a genus of laminoid camelids that evolved in North America in the Miocene period about 10 million years ago. This genus diversified and expanded into to South America in the Late Pliocene approximately 3 to 2 million years ago, as part of the Great American Biotic Interchange. The genus became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. The monophyly of the genus has been considered questionable, with phylogenetic analyses finding the genus to paraphyletic or polyphyletic, with some species suggested to be more closely related to living lamines than to other Hemiaucenia species.

Catonyx is an extinct genus of ground sloth of the family Scelidotheriidae, endemic to South America during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. It lived from 2.5 Ma to about 10,000 years ago, existing for approximately 2.49 million years. The most recent date obtained is about 9600 B.P.

Scelidodon is an extinct genus of South American ground sloths. Its remains have been found in the Yupoí and Uspara Formations of Argentina, the Ulloma, Umala, Ñuapua and Tarija Formations of Bolivia, in Brazil, in Chile and in Peru. The youngest fossils have been dated to as recently as 9000 B.P.

Camelinae is a subfamily of artiodactyls of the family Camelidae. Camelinae include the tribes Camelini and Lamini. A third tribe, Camelopini, created by S. D. Webb (1965), was formerly included, but was discarded by J. A. Harrison (1979) after it was shown to be polyphyletic: it consisted of the genera Camelops and Megatylopus, which were moved to Camelini and Lamini respectively.

Notiomastodon is an extinct genus of gomphothere proboscidean, endemic to South America from the Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene. Notiomastodon specimens reached a size similar to that of the modern Asian elephant. Like other brevirostrine gomphotheres such as Cuvieronius and Stegomastodon, Notiomastodon had a shortened lower jaw and lacked lower tusks, unlike more primitive gomphotheres like Gomphotherium.

Arctotherium is an extinct genus of the Pleistocene short-faced bears endemic to Central and South America. Arctotherium migrated from North America to South America during the Great American Interchange, following the formation of the Isthmus of Panama during the late Pliocene. The genus consists of one early giant form, A. angustidens, and several succeeding smaller species, which were within the size range of modern bears. Arctotherium was adapted to open and mixed habitat. They are genetically closer to the spectacled bear, than to Arctodus of North America, implying the two extinct forms evolved large size in a convergent manner.

Lamini is a tribe of the subfamily Camelinae. It contains one extant genus with four species, all exclusively from South America: llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. The former two are domesticated species, while the latter two are only found in the wild. None display sexual dimorphism. The four species can interbreed and produce fertile offspring. Additionally, there are several extinct genera.

The Manix Formation is a geologic formation in California. This formation dates to the Pleistocene Epoch and is known to preserve fossils. Specimens of the extinct camelid, Camelops have been uncovered from the Rancholabrean units of this formation of both the species C. hesternus and C. minidokae.

Praemegaceros is an extinct genus of deer, known from the Pleistocene and Holocene of Western Eurasia. It contains the subgenera Praemegaceros,Orthogonoceros and Nesoleipoceros. It has sometimes been synonymised with Megaloceros and Megaceroides, however they have been found to be generically distinct.

Morenelaphus is an extinct genus of capreoline deer that lived in South America during the Pleistocene, ranging from the Pampas to southern Bolivia and Northeast Brazil. There is only a single recognised species, Morenelaphus brachyceros. It was a large deer, with some specimens estimated to exceed 200 kilograms in body mass. The antlers were over 70 cm in length, and are superficially similar those of deer belonging to the subfamily Cervinae, like red deer. Fossils of the genus have been recovered from the Agua Blanca, Fortín Tres Pozos and Luján Formations of Argentina, the Ñuapua Formation of Bolivia, Santa Vitória do Palmar in southern Brazil, Paraguay and the Sopas Formation of Uruguay.

Neolicaphrium is an extinct genus of ungulate mammal belonging to the extinct order Litopterna. This animal lived from the Late Pliocene (Chapadmalalan) to the Late Pleistocene (Lujanian) in southern South America, being the last survivor of the family Proterotheriidae.