Paleontology in Maryland refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Maryland. The invertebrate fossils of Maryland are similar to those of neighboring Delaware. For most of the early Paleozoic era, Maryland was covered by a shallow sea, although it was above sea level for portions of the Ordovician and Devonian. The ancient marine life of Maryland included brachiopods and bryozoans while horsetails and scale trees grew on land. By the end of the era, the sea had left the state completely. In the early Mesozoic, Pangaea was splitting up. The same geologic forces that divided the supercontinent formed massive lakes. Dinosaur footprints were preserved along their shores. During the Cretaceous, the state was home to dinosaurs. During the early part of the Cenozoic era, the state was alternatingly submerged by sea water or exposed. During the Ice Age, mastodons lived in the state.

Paleontology in Pennsylvania refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The geologic column of Pennsylvania spans from the Precambrian to Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Pennsylvania was submerged by a warm, shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The armored fish Palaeaspis appeared during the Silurian. By the Devonian the state was home to other kinds of fishes. On land, some of the world's oldest tetrapods left behind footprints that would later fossilize. Some of Pennsylvania's most important fossil finds were made in the state's Devonian rocks. Carboniferous Pennsylvania was a swampy environment covered by a wide variety of plants. The latter half of the period was called the Pennsylvanian in honor of the state's rich contemporary rock record. By the end of the Paleozoic the state was no longer so swampy. During the Mesozoic the state was home to dinosaurs and other kinds of reptiles, who left behind fossil footprints. Little is known about the early to mid Cenozoic of Pennsylvania, but during the Ice Age it seemed to have a tundra-like environment. Local Delaware people used to smoke mixtures of fossil bones and tobacco for good luck and to have wishes granted. By the late 1800s Pennsylvania was the site of formal scientific investigation of fossils. Around this time Hadrosaurus foulkii of neighboring New Jersey became the first mounted dinosaur skeleton exhibit at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The Devonian trilobite Phacops rana is the Pennsylvania state fossil.

Paleontology in New Jersey refers to paleontological research in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The state is especially rich in marine deposits.

Paleontology in Georgia refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Georgia. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Georgia was largely covered by seawater. Although no major Paleozoic discoveries have been uncovered in Georgia, the local fossil record documents a great diversity of ancient life in the state. Inhabitants of Georgia's early Paleozoic sea included corals, stromatolites, and trilobites. During the Carboniferous local sea levels dropped and a vast complex of richly vegetated delta formed in the state. These swampy deltas were home to early tetrapods which left behind footprints that would later fossilize. Little is known of Triassic Georgia and the Jurassic is absent altogether from the state's rock record. During the Cretaceous, however, southern Georgia was covered by a sea that was home to invertebrates and fishes. On land, the tree Araucaria grew, and dinosaurs inhabited the state. Southern Georgia remained submerged by shallow seawater into the ensuing Paleogene and Neogene periods of the Cenozoic era. These seas were home to small coral reefs and a variety of other marine invertebrates. By the Pleistocene the state was mostly dry land covered in forests and grasslands home to mammoths and giant ground sloths. Local coal mining activity has a history of serendipitous Carboniferous-aged fossil discoveries. Another major event in Georgian paleontology was a 1963 discovery of Pleistocene fossils in Bartow County. Shark teeth are the Georgia state fossil.

Paleontology in New York refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New York. New York has a very rich fossil record, especially from the Devonian. However, a gap in this record spans most of the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic.

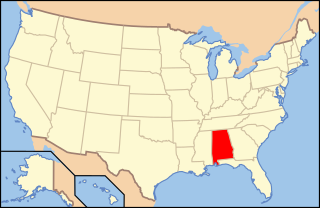

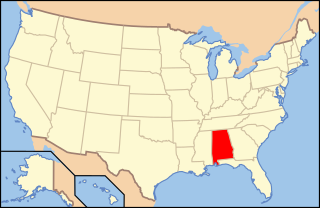

Paleontology in Alabama refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alabama. Pennsylvanian plant fossils are common, especially around coal mines. During the early Paleozoic, Alabama was at least partially covered by a sea that would end up being home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and graptolites. During the Devonian the local seas deepened and local wildlife became scarce due to their decreasing oxygen levels.

Paleontology in Arkansas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Arkansas. The fossil record of Arkansas spans from the Ordovician to the Eocene. Nearly all of the state's fossils have come from ancient invertebrate life. During the early Paleozoic, much of Arkansas was covered by seawater. This sea would come to be home to creatures including Archimedes, brachiopods, and conodonts. This sea would begin its withdrawal during the Carboniferous, and by the Permian the entire state was dry land. Terrestrial conditions continued into the Triassic, but during the Jurassic, another sea encroached into the state's southern half. During the Cretaceous the state was still covered by seawater and home to marine invertebrates such as Belemnitella. On land the state was home to long necked sauropod dinosaurs, who left behind footprints and ostrich dinosaurs such as Arkansaurus.

Paleontology in Minnesota refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Minnesota. The geologic record of Minnesota spans from Precambrian to recent with the exceptions of major gaps including the Silurian period, the interval from the Middle to Upper Devonian to the Cretaceous, and the Cenozoic. During the Precambrian, Minnesota was covered by an ocean where local bacteria ended up forming banded iron formations and stromatolites. During the early part of the Paleozoic era southern Minnesota was covered by a shallow tropical sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, massive cephalopods, corals, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The sea withdrew from the state during the Silurian, but returned during the Devonian. However, the rest of the Paleozoic is missing from the local rock record. The Triassic is also missing from the local rock record and Jurassic deposits, while present, lack fossils. Another sea entered the state during the Cretaceous period, this one inhabited by creatures like ammonites and sawfish. Duckbilled dinosaurs roamed the land. The Paleogene and Neogene periods of the ensuing Cenozoic era are also missing from the local rock record, but during the Ice Age evidence points to glacial activity in the state. Woolly mammoths, mastodons, and musk oxen inhabited Minnesota at the time. Local Native Americans interpreted such remains as the bones of the water monster Unktehi. They also told myths about thunder birds that may have been based on Ice Age bird fossils. By the early 19th century, the state's fossil had already attracted the attention of formally trained scientists. Early research included the Cretaceous plant discoveries made by Leo Lesquereux.

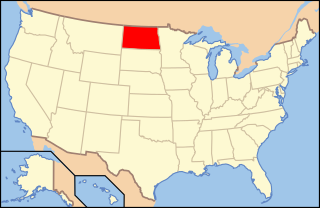

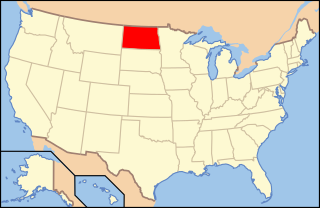

Paleontology in North Dakota refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of North Dakota. During the early Paleozoic era most of North Dakota was covered by a sea home to brachiopods, corals, and fishes. The sea briefly left during the Silurian, but soon returned, until once more starting to withdraw during the Permian. By the Triassic some areas of the state were still under shallow seawater, but others were dry and hot. During the Jurassic subtropical forests covered the state. North Dakota was always at least partially under seawater during the Cretaceous. On land Sequoia grew. Later in the Cenozoic the local seas dried up and were replaced by subtropical swamps. Climate gradually cooled until the Ice Age, when glaciers entered the area and mammoths and mastodons roamed the local woodlands.

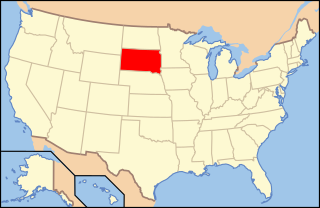

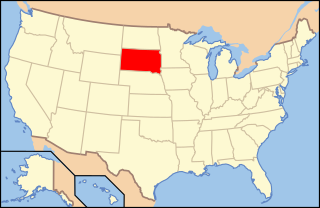

Paleontology in South Dakota refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of South Dakota. South Dakota is an excellent source of fossils as finds have been widespread throughout the state. During the early Paleozoic era South Dakota was submerged by a shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, cephalopods, corals, and ostracoderms. Local sea levels rose and fall during the Carboniferous and the sea left completely during the Permian. During the Triassic, the state became a coastal plain, but by the Jurassic it was under a sea where ammonites lived. Cretaceous South Dakota was also covered by a sea that was home to mosasaurs. The sea remained in place after the start of the Cenozoic before giving way to a terrestrial mammal fauna including the camel Poebrotherium, three-toed horses, rhinoceroses, saber-toothed cat, and titanotheres. During the Ice Age glaciers entered the state, which was home to mammoths and mastodons. Local Native Americans interpreted fossils as the remains of the water monster Unktehi and used bits of Baculites shells in magic rituals to summon buffalo herds. Local fossils came to the attention of formally trained scientists with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Cretaceous horned dinosaur Triceratops horridus is the South Dakota state fossil.

Paleontology in Nebraska refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Nebraska. Nebraska is world-famous as a source of fossils. During the early Paleozoic, Nebraska was covered by a shallow sea that was probably home to creatures like brachiopods, corals, and trilobites. During the Carboniferous, a swampy system of river deltas expanded westward across the state. During the Permian period, the state continued to be mostly dry land. The Triassic and Jurassic are missing from the local rock record, but evidence suggests that during the Cretaceous the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, where ammonites, fish, sea turtles, and plesiosaurs swam. The coasts of this sea were home to flowers and dinosaurs. During the early Cenozoic, the sea withdrew and the state was home to mammals like camels and rhinoceros. Ice Age Nebraska was subject to glacial activity and home to creatures like the giant bear Arctodus, horses, mammoths, mastodon, shovel-tusked proboscideans, and Saber-toothed cats. Local Native Americans devised mythical explanations for fossils like attributing them to water monsters killed by their enemies, the thunderbirds. After formally trained scientists began investigating local fossils, major finds like the Agate Springs mammal bone beds occurred. The Pleistocene mammoths Mammuthus primigenius, Mammuthus columbi, and Mammuthus imperator are the Nebraska state fossils.

Paleontology in Texas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Texas. Author Marian Murray has said that "Texas is as big for fossils as it is for everything else." Some of the most important fossil finds in United States history have come from Texas. Fossils can be found throughout most of the state. The fossil record of Texas spans almost the entire geologic column from Precambrian to Pleistocene. Shark teeth are probably the state's most common fossil. During the early Paleozoic era Texas was covered by a sea that would later be home to creatures like brachiopods, cephalopods, graptolites, and trilobites. Little is known about the state's Devonian and early Carboniferous life. Evidence indicates that during the late Carboniferous the state was home to marine life, land plants and early reptiles. During the Permian, the seas largely shrank away, but nevertheless coral reefs formed in the state. The rest of Texas was a coastal plain inhabited by early relatives of mammals like Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus. During the Triassic, a great river system formed in the state that was inhabited by crocodile-like phytosaurs. Little is known about Jurassic Texas, but there are fossil aquatic invertebrates of this age like ammonites in the state. During the Early Cretaceous local large sauropods and theropods left a great abundance of footprints. Later in the Cretaceous, the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway and home to creatures like mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and few icthyosaurs. Early Cenozoic Texas still contained areas covered in seawater where invertebrates and sharks lived. On land the state would come to be home to creatures like glyptodonts, mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, giant ground sloths, titanotheres, uintatheres, and dire wolves. Archaeological evidence suggests that local Native Americans knew about local fossils. Formally trained scientists were already investigating the state's fossils by the late 1800s. In 1938, a major dinosaur footprint find occurred near Glen Rose. Pleurocoelus was the Texas state dinosaur from 1997 to 2009, when it was replaced by Paluxysaurus jonesi after the Texan fossils once referred to the former species were reclassified to a new genus.

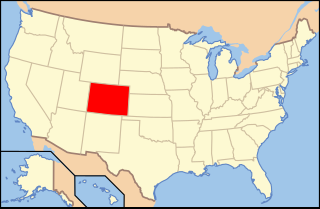

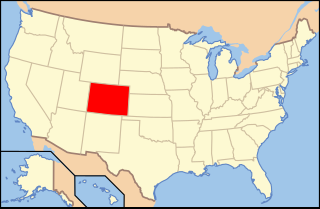

Paleontology in Wyoming includes research into the prehistoric life of the U.S. state of Wyoming as well as investigations conducted by Wyomingite researchers and institutions into ancient life occurring elsewhere.

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

Paleontology in New Mexico refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New Mexico. The fossil record of New Mexico is exceptionally complete and spans almost the entire stratigraphic column. More than 3,300 different kinds of fossil organisms have been found in the state. Of these more than 700 of these were new to science and more than 100 of those were type species for new genera. During the early Paleozoic, southern and western New Mexico were submerged by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, cartilaginous fishes, corals, graptolites, nautiloids, placoderms, and trilobites. During the Ordovician the state was home to algal reefs up to 300 feet high. During the Carboniferous, a richly vegetated island chain emerged from the local sea. Coral reefs formed in the state's seas while terrestrial regions of the state dried and were home to sand dunes. Local wildlife included Edaphosaurus, Ophiacodon, and Sphenacodon.

Paleontology in Idaho refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Idaho. The fossil record of Idaho spans much of the geologic column from the Precambrian onward. During the Precambrian, bacteria formed stromatolites while worms left behind trace fossils. The state was mostly covered by a shallow sea during the majority of the Paleozoic era. This sea became home to creatures like brachiopods, corals and trilobites. Idaho continued to be a largely marine environment through the Triassic and Jurassic periods of the Mesozoic era, when brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, ichthyosaurs and sharks inhabited the local waters. The eastern part of the state was dry land during the ensuing Cretaceous period when dinosaurs roamed the area and trees grew which would later form petrified wood.

Paleontology in Utah refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Utah. Utah has a rich fossil record spanning almost all of the geologic column. During the Precambrian, the area of northeastern Utah now occupied by the Uinta Mountains was a shallow sea which was home to simple microorganisms. During the early Paleozoic Utah was still largely covered in seawater. The state's Paleozoic seas would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, fishes, and trilobites. During the Permian the state came to resemble the Sahara desert and was home to amphibians, early relatives of mammals, and reptiles. During the Triassic about half of the state was covered by a sea home to creatures like the cephalopod Meekoceras, while dinosaurs whose footprints would later fossilize roamed the forests on land. Sand dunes returned during the Early Jurassic. During the Cretaceous the state was covered by the sea for the last time. The sea gave way to a complex of lakes during the Cenozoic era. Later, these lakes dissipated and the state was home to short-faced bears, bison, musk oxen, saber teeth, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. Formally trained scientists have been aware of local fossils since at least the late 19th century. Major local finds include the bonebeds of Dinosaur National Monument. The Jurassic dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis is the Utah state fossil.

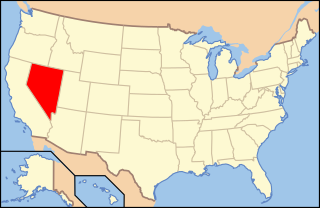

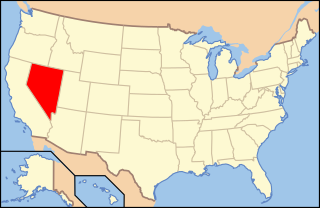

Paleontology in Nevada refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Nevada. Nevada has a rich fossil record of plants and animal life spanning the past 650 million years of time. The earliest fossils from the state are from Esmeralda County, and are Late Proterozoic in age and represent stromatolite reefs of cyanobacteria, amongst these reefs were some of the oldest known shells in the fossil record, the Cloudina-fauna. Much of the Proterozoic and Paleozoic fossil story of Nevada is that of a warm, shallow, tropical sea, with a few exceptions towards the Late Paleozoic. As such, many fossils across the state are those of marine animals, such as trilobites, brachiopods, bryozoans, honeycomb corals, archaeocyaths, and horn corals.

Paleontology in Washington encompasses paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Washington. Washington has a rich fossil record spanning almost the entire geologic column. Its fossil record shows an unusually great diversity of preservational types including carbonization, petrifaction, permineralization, molds, and cast. Early Paleozoic Washington would come to be home to creatures like archaeocyathids, brachiopods, bryozoans, cephalopods, corals, and trilobites. While some Mesozoic fossils are known, few dinosaur remains have been found in the state. Only about two-thirds of the state's land mass had come together by the time the Mesozoic ended. In the Cenozoic the state's sea began to withdraw towards the west, while local terrestrial environments were home to a rich variety of trees and insects. Vertebrates would come to include the horse Hipparion, bison, camels, caribou, oreodonts. Later, during the Ice Age, the northern third of the state was covered in glaciers while creatures like bison, caribou, woolly mammoths, mastodons, and rhinoceros roamed elsewhere in the state. The Pleistocene Columbian Mammoth, Mammuthus columbi is the Washington state fossil.

The geological history of North America comprises the history of geological occurrences and emergence of life in North America during the interval of time spanning from the formation of the Earth through to the emergence of humanity and the start of prehistory. At the start of the Paleozoic Era, what is now "North" America was actually in the Southern Hemisphere. Marine life flourished in the country's many seas, although terrestrial life had not yet evolved. During the latter part of the Paleozoic, seas were largely replaced by swamps home to amphibians and early reptiles. When the continents had assembled into Pangaea, drier conditions prevailed. The evolutionary precursors to mammals dominated the country until a mass extinction event ended their reign.