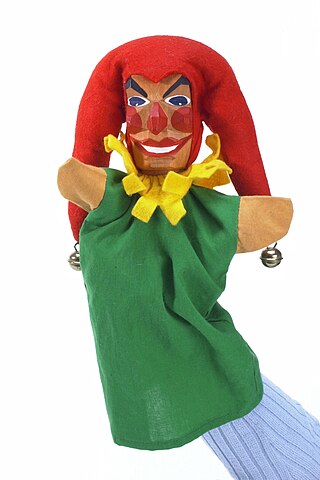

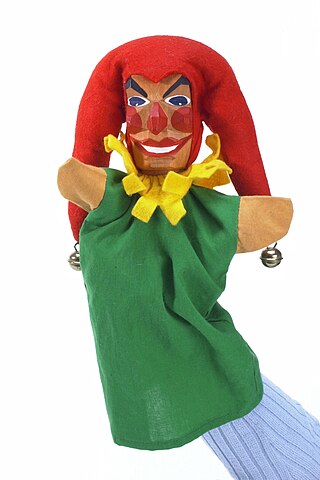

Punch and Judy is a traditional puppet show featuring Mr. Punch and his wife Judy. The performance consists of a sequence of short scenes, each depicting an interaction between two characters, most typically the anarchic Mr. Punch and one other character who usually falls victim to the intentional violence of Punch's slapstick. First appearing in England in 1662, The Daily Telegraph called Punch and Judy "a staple of the British seaside scene". The various episodes of Punch comedy—often provoking shocked laughter—are dominated by the clowning of Mr. Punch.

Harlequin is the best-known of the comic servant characters (Zanni) from the Italian commedia dell'arte, associated with the city of Bergamo. The role is traditionally believed to have been introduced by the Italian actor-manager Zan Ganassa in the late 16th century, was definitively popularized by the Italian actor Tristano Martinelli in Paris in 1584–1585, and became a stock character after Martinelli's death in 1630.

Zanni, Zani or Zane is a character type of commedia dell'arte best known as an astute servant and a trickster. The Zanni comes from the countryside and is known to be a "dispossessed immigrant worker". Through time, the Zanni grew to be a popular figure who was first seen in commedia as early as the 14th century. The English word zany derives from this character. The longer the nose on the characters mask, the more foolish the character.

Brighella is a comic, masked character from the Italian theatre style commedia dell'arte. His early costume consisted of loosely fitting, white smock and pants with green trim and was often equipped with a batocio or slapstick, or else with a wooden sword. Later, he took to wearing a sort of livery with a matching cape. He wore a greenish half-mask displaying a look of preternatural lust and greed. It is distinguished by a hook nose and thick lips, along with a thick twirled mustache to give him an offensive characteristic. He evolved out of the general Zanni, as evidenced by his costume, and came into his own around the start of the 16th century.

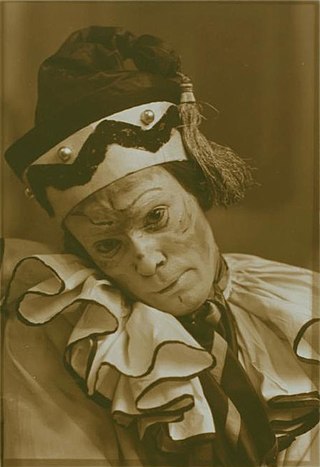

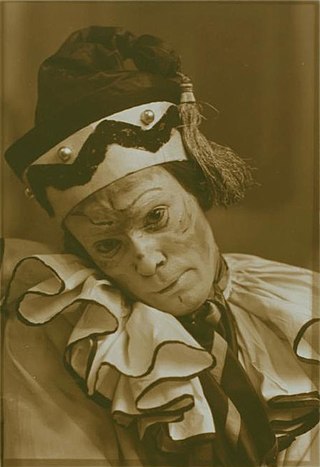

Pierrot, a stock character of pantomime and commedia dell'arte, has his origins in the late 17th-century Italian troupe of players performing in Paris and known as the Comédie-Italienne. The name is a diminutive of Pierre (Peter), using the suffix -ot and derives from the Italian Pedrolino. His character in contemporary popular culture—in poetry, fiction, and the visual arts, as well as works for the stage, screen, and concert hall—is that of the sad clown, often pining for love of Columbine. Performing unmasked, with a whitened face, he wears a loose white blouse with large buttons and wide white pantaloons. Sometimes he appears with a frilled collaret and a hat, usually with a close-fitting crown and wide round brim and, more rarely, with a conical shape like a dunce's cap.

Puppetry is a form of theatre or performance that involves the manipulation of puppets – inanimate objects, often resembling some type of human or animal figure, that are animated or manipulated by a human called a puppeteer. Such a performance is also known as a puppet production. The script for a puppet production is called a puppet play. Puppeteers use movements from hands and arms to control devices such as rods or strings to move the body, head, limbs, and in some cases the mouth and eyes of the puppet. The puppeteer sometimes speaks in the voice of the character of the puppet, while at other times they perform to a recorded soundtrack.

Pulcinella is a classical character that originated in commedia dell'arte of the 17th century and became a stock character in Neapolitan puppetry. Pulcinella's versatility in status and attitude has captivated audiences worldwide and kept the character popular in countless forms since his introduction to commedia dell'arte by Silvio Fiorillo in 1620.

The Atellan Farce, also known as the Oscan Games, were masked improvised farces in Ancient Rome. The Oscan athletic games were very popular, and usually preceded by longer pantomime plays. The origin of the Atellan Farce is uncertain, but the farces are similar to other forms of ancient theatre such as the South Italian Phlyakes, the plays of Plautus and Terence, and Roman mime. Most historians believe the name is derived from Atella, an Oscan town in Campania. The farces were written in Oscan and imported to Rome in 391 BC. In later Roman versions, only the ridiculous characters speak their lines in Oscan, while the others speak in Latin.

Petrushka is a ballet by Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1911 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company; the original choreography was by Michel Fokine and stage designs and costumes by Alexandre Benois, who assisted Stravinsky with the libretto. The ballet premiered at the Théâtre du Châtelet on 13 June 1911 with Vaslav Nijinsky as Petrushka, Tamara Karsavina as the lead ballerina, Alexander Orlov as the Moor, and Enrico Cecchetti the charlatan.

Shadow play, also known as shadow puppetry, is an ancient form of storytelling and entertainment which uses flat articulated cut-out figures which are held between a source of light and a translucent screen or scrim. The cut-out shapes of the puppets sometimes include translucent color or other types of detailing. Various effects can be achieved by moving both the puppets and the light source. A skilled puppeteer can make the figures appear to walk, dance, fight, nod and laugh.

Adult puppeteering is the use of puppets in contexts aimed at adult audiences. Serious theatrical pieces can use puppets, either for aesthetic reasons, or to achieve special effects that would otherwise be impossible with human actors. In parts of the world where puppet shows have traditionally been children's entertainment, many find the notion of puppets in decidedly adult situations—for example, involving drugs, sex, profanity, or violence—to be humorous, because of the bizarre contrast it creates between subject matter and characters.

Kasperle, Kasper, or Kasperl is a famous and traditional puppet character from Austria, German-speaking Switzerland, and Germany. Its roots date to 17th century, and it was at times so popular that Kasperltheater was synonymous with puppet theater. Kasperltheater includes various sets of puppets. In some German settings the following characters occur: Kasper, Gretel, Seppel, Grandmother, princess, king, witch, robber, and crocodile. In Austria, Kasperl usually occurs alongside Pezi, Buffi or Mimi, and usually Großmutter and Großvater. The older, more traditional Kasperle shows are very similar to "Mister Punch". There are also "Kasperle versions" of the Grimm and other fairy tales and of "modern fairy tales".

Max Jacob was a German puppeteer and the developer of the Hohnsteiner Kasper Theatre in the 1920s.

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. Puppetry is an ancient form of theatre which dates back to the 5th century BC in ancient Greece.

Commedia dell'arte was an early form of professional theatre, originating from Italian theatre, that was popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. It was formerly called Italian comedy in English and is also known as commedia alla maschera, commedia improvviso, and commedia dell'arte all'improvviso. Characterized by masked "types", commedia was responsible for the rise of actresses such as Isabella Andreini and improvised performances based on sketches or scenarios. A commedia, such as The Tooth Puller, is both scripted and improvised. Characters' entrances and exits are scripted. A special characteristic of commedia is the lazzo, a joke or "something foolish or witty", usually well known to the performers and to some extent a scripted routine. Another characteristic of commedia is pantomime, which is mostly used by the character Arlecchino, now better known as Harlequin.

Mamulengo is a type of puppet performance popular in North East Brazil, especially in the state of Pernambuco. The origin of the name is unclear, but it is believed that it originated with the Portuguese phrase mão molenga, meaning "soft hand", ideal for giving lively movements to a puppet.

Randal John Metz is a professional puppeteer and variety/stage performer. He is known for creating puppet productions, and puppet performer for Children’s Fairyland’s Open Storybook Puppet Theater in Oakland, California, the oldest continuously operating puppet theater in the United States. He currently produces seven different puppet shows a year for the theater, and tours his shows throughout California under the name The Puppet Company. He has served several terms as President and Vice-President of the San Francisco Bay Area Puppeteers Guild.

Nina Yakovlevna Simonovich-Efimova was a Russian artist, puppet designer and one of the first professional Russian puppeteers. Together with her husband Ivan Efimov she founded the tradition of Soviet puppet theater, acting as the driving force behind the Efimovs' presentations.

Ivan Efimov was a Russian sculptor. He was one of the members of the art association ‘The Four Arts’, which existed in Moscow and Leningrad in 1924-1931. Along with his wife, Nina Simonovich-Efimova, the couple founded the tradition of Soviet puppet theater. Since 1958 he has been an Honorary member of UNIMA. In addition to puppet design, Efimov was noted for his book illustration and sculpture. He created pieces for the Central Museum of Ethnology, the North River Terminal, several metro and railway stations and the Grand Kremlin Palace. Internationally his sculptures were awarded gold medals in 1937 at the Paris World Exhibition and a silver medal at the World Exhibition in Brussels, and in Russia he was honored as both an Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and the People’s Artist of the RSFSR.

Russian puppet theater appears to have originated either in migrations from the Byzantine Empire in the sixth century or possibly by Mongols travelling from China. Itinerant Slavic minstrels were presenting puppet shows in western Russia by the thirteenth century, arriving in Moscow in the mid-sixteenth century. Although Russian traditions were increasingly influenced by puppeteers from western Europe in the eighteenth century, Petrushka continued to be one of the principal figures. In addition to glove puppets and marionettes, rod puppets and flat puppets were introduced for a time but disappeared in the late nineteenth century.