Distillation, also classical distillation, is the process of separating the component substances of a liquid mixture of two or more chemically discrete substances; the separation process is realized by way of the selective boiling of the mixture and the condensation of the vapors in a still.

Raoult's law ( law) is a relation of physical chemistry, with implications in thermodynamics. Proposed by French chemist François-Marie Raoult in 1887, it states that the partial pressure of each component of an ideal mixture of liquids is equal to the vapor pressure of the pure component multiplied by its mole fraction in the mixture. In consequence, the relative lowering of vapor pressure of a dilute solution of nonvolatile solute is equal to the mole fraction of solute in the solution.

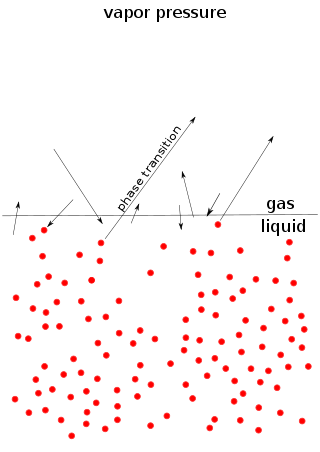

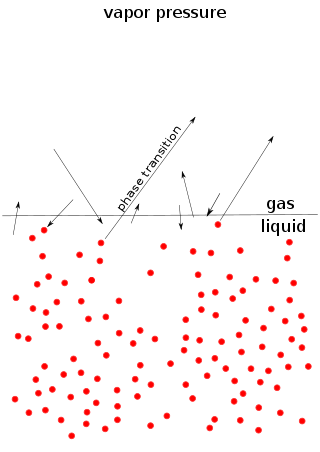

Vapor pressure or equilibrium vapor pressure is the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases at a given temperature in a closed system. The equilibrium vapor pressure is an indication of a liquid's thermodynamic tendency to evaporate. It relates to the balance of particles escaping from the liquid in equilibrium with those in a coexisting vapor phase. A substance with a high vapor pressure at normal temperatures is often referred to as volatile. The pressure exhibited by vapor present above a liquid surface is known as vapor pressure. As the temperature of a liquid increases, the attractive interactions between liquid molecules become less significant in comparison to the entropy of those molecules in the gas phase, increasing the vapor pressure. Thus, liquids with strong intermolecular interactions are likely to have smaller vapor pressures, with the reverse true for weaker interactions.

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas as if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature. The total pressure of an ideal gas mixture is the sum of the partial pressures of the gases in the mixture.

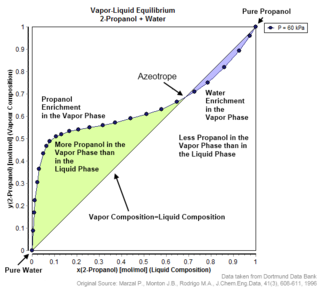

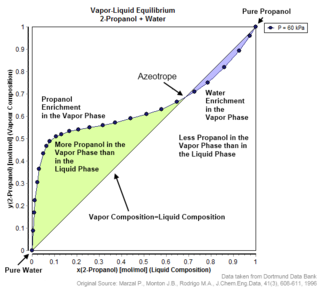

An azeotrope or a constant heating point mixture is a mixture of two or more liquids whose proportions cannot be changed by simple distillation. This happens because when an azeotrope is boiled, the vapour has the same proportions of constituents as the unboiled mixture. Knowing an azeotrope's behavior is important for distillation.

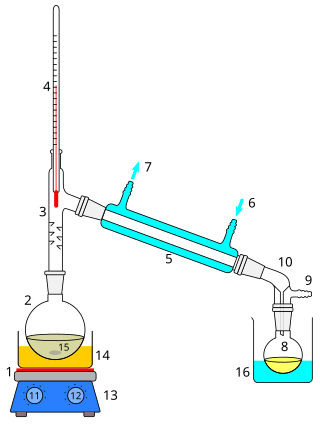

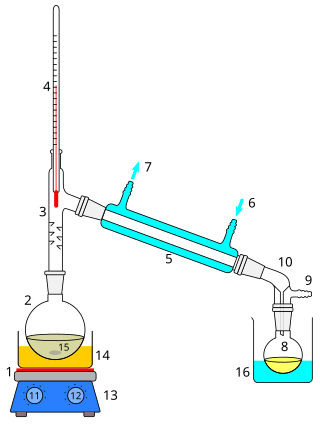

Fractional distillation is the separation of a mixture into its component parts, or fractions. Chemical compounds are separated by heating them to a temperature at which one or more fractions of the mixture will vaporize. It uses distillation to fractionate. Generally the component parts have boiling points that differ by less than 25 °C (45 °F) from each other under a pressure of one atmosphere. If the difference in boiling points is greater than 25 °C, a simple distillation is typically used.

In physical chemistry, Henry's law is a gas law that states that the amount of dissolved gas in a liquid is directly proportional at equilibrium to its partial pressure above the liquid. The proportionality factor is called Henry's law constant. It was formulated by the English chemist William Henry, who studied the topic in the early 19th century. In simple words, we can say that the partial pressure of a gas in vapour phase is directly proportional to the mole fraction of a gas in solution.

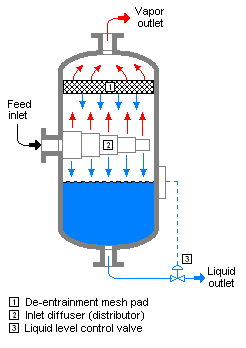

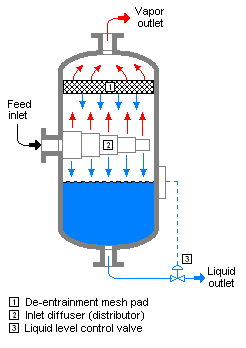

Flash evaporation is the partial vapor that occurs when a saturated liquid stream undergoes a reduction in pressure by passing through a throttling valve or other throttling device. This process is one of the simplest unit operations. If the throttling valve or device is located at the entry into a pressure vessel so that the flash evaporation occurs within the vessel, then the vessel is often referred to as a flash drum.

A fractionating column or fractional column is equipment used in the distillation of liquid mixtures to separate the mixture into its component parts, or fractions, based on their differences in volatility. Fractionating columns are used in small-scale laboratory distillations as well as large-scale industrial distillations.

Vacuum distillation or distillation under reduced pressure is a type of distillation performed under reduced pressure, which allows the purification of compounds not readily distilled at ambient pressures or simply to save time or energy. This technique separates compounds based on differences in their boiling points. This technique is used when the boiling point of the desired compound is difficult to achieve or will cause the compound to decompose. Reduced pressures decrease the boiling point of compounds. The reduction in boiling point can be calculated using a temperature-pressure nomograph using the Clausius–Clapeyron relation.

In chemistry, volatility is a material quality which describes how readily a substance vaporizes. At a given temperature and pressure, a substance with high volatility is more likely to exist as a vapour, while a substance with low volatility is more likely to be a liquid or solid. Volatility can also describe the tendency of a vapor to condense into a liquid or solid; less volatile substances will more readily condense from a vapor than highly volatile ones. Differences in volatility can be observed by comparing how fast substances within a group evaporate when exposed to the atmosphere. A highly volatile substance such as rubbing alcohol will quickly evaporate, while a substance with low volatility such as vegetable oil will remain condensed. In general, solids are much less volatile than liquids, but there are some exceptions. Solids that sublimate such as dry ice or iodine can vaporize at a similar rate as some liquids under standard conditions.

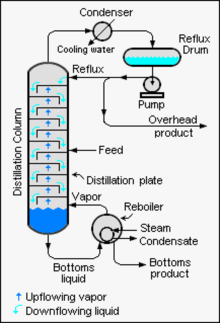

Continuous distillation, a form of distillation, is an ongoing separation in which a mixture is continuously fed into the process and separated fractions are removed continuously as output streams. Distillation is the separation or partial separation of a liquid feed mixture into components or fractions by selective boiling and condensation. The process produces at least two output fractions. These fractions include at least one volatile distillate fraction, which has boiled and been separately captured as a vapor condensed to a liquid, and practically always a bottoms fraction, which is the least volatile residue that has not been separately captured as a condensed vapor.

The Fenske equation in continuous fractional distillation is an equation used for calculating the minimum number of theoretical plates required for the separation of a binary feed stream by a fractionation column that is being operated at total reflux.

In thermodynamics and chemical engineering, the vapor–liquid equilibrium (VLE) describes the distribution of a chemical species between the vapor phase and a liquid phase.

Equilibrium isotope fractionation is the partial separation of isotopes between two or more substances in chemical equilibrium. Equilibrium fractionation is strongest at low temperatures, and forms the basis of the most widely used isotopic paleothermometers : D/H and 18O/16O records from ice cores, and 18O/16O records from calcium carbonate. It is thus important for the construction of geologic temperature records. Isotopic fractionations attributed to equilibrium processes have been observed in many elements, from hydrogen (D/H) to uranium (238U/235U). In general, the light elements are most susceptible to fractionation, and their isotopes tend to be separated to a greater degree than heavier elements.

This glossary of chemistry terms is a list of terms and definitions relevant to chemistry, including chemical laws, diagrams and formulae, laboratory tools, glassware, and equipment. Chemistry is a physical science concerned with the composition, structure, and properties of matter, as well as the changes it undergoes during chemical reactions; it features an extensive vocabulary and a significant amount of jargon.

The non-random two-liquid model is an activity coefficient model introduced by Renon and Prausnitz in 1968 that correlates the activity coefficients of a compound with its mole fractions in the liquid phase concerned. It is frequently applied in the field of chemical engineering to calculate phase equilibria. The concept of NRTL is based on the hypothesis of Wilson, who stated that the local concentration around a molecule in most mixtures is different from the bulk concentration. This difference is due to a difference between the interaction energy of the central molecule with the molecules of its own kind and that with the molecules of the other kind . The energy difference also introduces a non-randomness at the local molecular level. The NRTL model belongs to the so-called local-composition models. Other models of this type are the Wilson model, the UNIQUAC model, and the group contribution model UNIFAC. These local-composition models are not thermodynamically consistent for a one-fluid model for a real mixture due to the assumption that the local composition around molecule i is independent of the local composition around molecule j. This assumption is not true, as was shown by Flemr in 1976. However, they are consistent if a hypothetical two-liquid model is used. Models, which have consistency between bulk and the local molecular concentrations around different types of molecules are COSMO-RS, and COSMOSPACE.

PSRK is an estimation method for the calculation of phase equilibria of mixtures of chemical components. The original goal for the development of this method was to enable the estimation of properties of mixtures containing supercritical components. This class of substances cannot be predicted with established models, for example UNIFAC.

A residue curve describes the change in the composition of the liquid phase of a chemical mixture during continuous evaporation at the condition of vapor–liquid equilibrium. Multiple residue curves for a single system are called residue curves map.

Aspen Plus, Aspen HYSYS, ChemCad and MATLAB, PRO are the commonly used process simulators for modeling, simulation and optimization of a distillation process in the chemical industries. Distillation is the technique of preferential separation of the more volatile components from the less volatile ones in a feed followed by condensation. The vapor produced is richer in the more volatile components. The distribution of the component in the two phase is governed by the vapour-liquid equilibrium relationship. In practice, distillation may be carried out by either two principal methods. The first method is based on the production of vapor boiling the liquid mixture to be separated and condensing the vapors without allowing any liquid to return to the still. There is no reflux. The second method is based on the return of part of the condensate to still under such conditions that this returning liquid is brought into intimate contact with the vapors on their way to condenser.