The Puja

According to Munshi Abdul Karim in Kavivallabha, Satyanārāyaṇa Punthi (1914-1915), and some secondary literature during the reign of the caliph Al-Muqtadir there was a Persian Sufi in Baghdad named Mansur Hāllāj who would repeat the phrase "Ānal Haq" or "I am Truth", even after he was killed by the caliph, cut into pieces, and burnt into ash. Karim states that this Sufi saint became known as Satya Pīr to Indian Muslims and Satyanārāyaṇa to Indian Hindus who were identical. Karim further states that Satyanārāyaṇa is not found among the lists of the names of the gods in the Hindu Shastras, is not mentioned by any Vaishnava poets, but is mentioned in the Revā Khaṇḍa of the Skanda Purāṇa. Karim also states that Old Bengali poets who write about Satyanārāyaṇa do so with accounts differing from that of the Revā Khaṇḍa, and also that the food offered to Satyanārāyaṇa by Hindus is the exact same as the food offered to Satya Pīr by Muslims. Satya Chandra Mitra rejects these arguments, stating there is no historical evidence of anyone named Mansur Hāllāj and that Hindus have never appropriated foreign saints into their own worship. He states the omission of Satyanārāyaṇa by Vaishnava poets and the alternative accounts of Old Bengali poets are not strong arguments for the recentness of Satyanārāyaṇa worship. Mitra, relying on the authenticity of the antiquity of the Purāṇas, states that its inclusion in the Revā Khaṇḍa is solid proof of the older origins of Satyanārāyaṇa worship. He also notes that the modern association between Satyanārāyaṇa and Satya Pīr is found only in Bengal, whereas in Bihar and Upper India Satyanārāyaṇa is worshipped purely as a form of Viṣṇu. [1] According to Stewart, Hindus considered Satya Pir to be a Kali Yuga incarnation of Viṣṇu, while Muslims considered him to be a pir, sometimes loosely connected to the historical Manṣūr al-Ḥallāj of Mecca or a local Bengali pir. [2] There is also "thin" evidence that Satya Pīr was the son of the daughter of Alauddin Husain Shah. According to Stewart, the biography of Satya Pīr is fictional. [3]

The Satya-nārāyaṇa-vrata-kathā is a short work found in the Itihāsa-samuccaya. The Itihāsa-samuccaya is a collection of anecdotes from the Mahābhārata, however Haraprasāda Śāstrī notes that the Satya-nārāyaṇa-vrata-kathā is not actually found in the Mahābhārata itself. The instructions for the Satya-nārāyaṇa-vrata-kathā are found the Revā Khaṇḍa of the Skanda Purāṇa which he states is a "very modern work". Śāstrī states the Satya-nārāyaṇa-vrata-kathā is also "very modern work" and the pūjā is of Islamic origins and style, and was originally and still called Satya Pīr Pūjā. [4]

R. C. Hazra states the worship of Satyanārāyaṇa is described in the Pratisarga-parvan of the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa and the Revā Khaṇḍa of the Vaṅgavāsī Press (Calcutta) edition of the Skanda Purāṇa. When examining the differences between the Veṅkateśvara Press (Bombay) edition and the Vaṅgavāsī Press edition, Hazra notes the entire Revā Khaṇḍa is only found in the Vaṅgavāsī edition, and that the editor of the Vaṅgavāsī Press edition stated he took the Veṅkaṭeśvara Press edition as his basis and then added various chapters and verses found in Bengal manuscripts. [5]

Pandurang Vaman Kane states that the Satya-nārāyaṇavrata is very popular in Bengal and Maharashtra among the lower middle class and women, and has its scriptural basis in the Pratisargaparvan of the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa and Vangavāsī edition of the Revā Khaṇḍa of the Skanda Purāṇa (the story is not founded in the Venkateswar Press edition of the Skanda Purāṇa). Kane summarizes the rite in which the worshipper prepares an offering of plantains, ghee, milk, wheat flour, and jaggery for Satyanārāyaṇa, and listens to the stories and engages in revelry, following which all the worshipper's desires are fulfilled. Kane notes that in the stories Satyanārāyaṇa is very jealous and vindictive. [6]

The legend of Satyanārāyaṇa is found in the Pratisargaparvan of the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa . According to this account, once Śaunaka and other r̥ṣī s were in Naimiṣāraṇya (forest) and asked Sūta about a rite suitable for Kali Yuga. Sūta states that worship of Satyanārāyaṇa is suitable for Kaliyuga, and states that once Nārada was roaming the world and was disheartened by the suffering of mortal beings. Thus he approached Viṣṇu, who told Nārada about the Satyanārāyaṇavratakathā. Once there was a beggar Brahmin named Śatānanda who lived in Kāśī. Viṣṇu, in the guise of an old Brahmin, instructed Śatānanda in the worship of Satyanārāyaṇa, and the Brahmin was able to achieve riches without begging. Once the king of Kedāramaṇipūraka, Candracūḍa, was defeated by his enemies in the Vindhyā mountains. Disheartened, he became an ascetic and travelled to Kāśī. There he saw people engaged in the worship of Nārāyaṇa, and curious, he asked Śatānanda to teach him about the worship of Satyanārāyaṇa. After gaining this knowledge, Candracūḍa returned to Kedāramaṇi and achieved victory over his enemies. Once a Niṣādha or Bhilla wood carrier reached Kāśī where he saw the worship of Satyanārāyaṇa being performed. The wood carrier learned the manner of Satyanārāyaṇa worship from Śatānanda, and returning to his home he performed the appropriate rites and the Bhillas achieved wealth and happiness. Once in Ratnapura, a merchant named Lakṣapati was walking along the riverbank where he observed Satyanārāyaṇa being worshipped. Lakṣapati, being childless, asked the worshippers if his desires would be fulfilled, to which they agreed. Eventually Lakṣapati and his wife Līlāvatī had a daughter named Kalāvatī. Kalāvatī eventually was married to a young merchant named Śaṅkhapati who began living with his in-laws. Lakṣapati performed the Satyanārāyaṇa worship rite, but left it incomplete. This led to him and his son-in-law being framed for theft of pearls from the king and being imprisoned. Kalāvatī eventually properly performed the Satyanārāyaṇa rite, upon which Nārāyaṇa himself appeared to the king in a dream in the form of a Brahmin and ordered him to let Lakṣapati and Śaṅkhapati be free. Upon being freed, Lakṣapati still neglected to perform Satyanārāyaṇa worship, which led to his mercantile goods on ships to be sunk. Lakṣapati eventually learns that his neglect of Satyanārāyana worship was the cause for his miseries, and returns to his family. However, in her excitement to see her father, Lilāvatī rush out of the house leaving the Satyanārāyaṇa rite incomplete, leading to the ship her husband was on to sink. Disheartened, she calls on Satyanārāyaṇa who tells her she will regain her husband, and the family properly performs the worship of Satyanārāyaṇa. [7]

H. R. Divekar was unable to find the Satyanārāyaṇa Kathā in any printed edition of the Skanda Purāṇa. He found that the kathā was included in Kalyāṇa, a Hindi translation of the Skanda Purāṇa, but the author of that translation admitted that the kathā was not in the original text, but merely in Bengali books which is why it was included. Divekar believes that the pujā is of Bengali origin derived from the worship of Saccā Pīr who was worshipped by Muslims and Hindus, and who was then fashioned into Satyanārāyaṇa by some Brahmin. Divekar notes that there is no special day for which the Satyanārāyaṇa pūjā is recommended, no restriction on being conducted on the basis of caste or gender, no observation of purity or fasting rather being associated with dancing, singing, and reveling. For these features Divekar states the pūjā became popular en masse. He concludes that the word Skanda Purāṇa is actually a misreading for skanna purāṇa "lost purāṇa". Bühnemann considers that reading to be unlikely. [8]

Roy states that the mention of Satya-nārāyan in the Skanda Purāṇa is an interpolation written in order to dislodge the worship of Satya-pir. He states the main two stories about Satya Pir revolved around a Brahmin and a sea merchant. The first involved a Brahmin who refuses to worship God in the form of a Muslim mendicant until he reappears in the form of Krishna. In the other tale a sea-merchant and his son refuse to worship Satya Pir until the merchant's daughter's devotion to Satya Pir saves their fleet from a storm. Roy states these two tales note the beginnings of upper class Hindu acceptance of Satya Pir worship. Initially there was a strong opposition to the worship of Satya Pir by orthodox Hindu brahmins, who then sought to integrate Satya Pir worship into existing Hindu beliefs while expunging the Islamic connections. However the attempt to completely supplant Satya Pir worship with Satya-nārāyan worship was partially unsuccessful, and large masses of Bengalis continued to recognize the syncretism of the two. He quotes several Muslim writers that were compiled in the Bānglā Sāhityer Itihās that use phrases such as "Satya-pir-narayan" or "Pir-narayan" or call Satya Pir identical to the Hindu Trimurti. [10]

According to Bühnemann, the Satyanārāyaṇa-vrata-kathā is found in the 1912 Bengali script Vaṅgavāṣī Press reprint of the published Skanda Purāṇa edition by Gurumaṇḍal, not in the Venkateśvar Press edition of Bombay. She states the actual kathā is only narrated after the completion of the Revā Khaṇḍa, thus pointing to it being a later addition. Comparing the kathās from the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa and the Bengali recension of the Skanda Purāṇa, she states that the vrata-kathā in the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa is more sophisticated and has more complicated rules for the performance of the pūjā. The Bengali Skanda Purāṇa makes no mention of the tale of Candracūḍa and moves straight into the story of the wood-cutter, who is not stated to be a Bhilla as in the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa. The name of Kalāvatī's husband is omitted in the Bengali Skanda Purāṇa, but the name of the king who Lakṣapati is framed from stealing from is named to be Candraketu. The Bengali Skanda Purāṇa also adds a story at the end in which a king named Vaṁśadhvaja arrogantly refuses to worship Satyanārāyaṇa and thus falls into misfortune until his repentance. The Bengali Skanda Purāṇa gives very little information about how the pūjā should actually be performed, unlike the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa. She also notes the term Satyanārāyaṇa as an epithet of Viṣṇu is not mentioned in older texts and the pūjā is not mentioned in the Shastras, further evidence of its later date. Imitations of the Satyanārāyaṇa-vrata-kathā exist whose inception is also attributed to the Purāṇas, such as that of Satya-vināyaka (ascribed to the Brahmāṇḍa Purāṇa ), Satya-ambā (ascribed to the Bhaviṣyottara Purāṇa ), and Satya-datta (composed by Vasudevānand Sarasvatī (1854--1914 A.D.)). [11]

Sarma notes that Satyanārāyaṇa is not mentioned in the Bombay edition of the Skanda Purāṇa, and that the editor of the Bengali edition clearly states that he included it because it was in some Bengali books and because the worship of Satyanārāyaṇa was popular in Bengal. Sarma regards Satyanārāyaṇa as a Sanskritization of the Islamic saint Satya Pīr who was worshipped by Muslims and Hindus with śinni. He notes the Bengali tales or vrata kathās which consider Satyanārāyaṇa and Satya Pīr to be identical, and states the worship of the deity originated in Bengal before spreading throughout northern India. [12]

G. V. Tagare, in the introduction to his English translation of the printed Venkateshwar Press Skanda Purāṇa as part of the Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology series, states the Satya-nārāyaṇa-māhātmya is "spurious". He states the Skanda Purāṇa is found in two forms, one that is divided into six Saṁhitās and another divided into seven Khaṇḍas. The seven Khaṇḍas are entitled: Māheśvara, Vaiṣṇava, Brāhma, Kāśī, Avantī, Nāgara, and Prabhāsa. He notes there are four printed versions of the Khaṇḍa form of the Skanda Purāṇa, that of the Venkateshwar Press, Bangavasi, Naval Kishore Press of Lucknow, and the Gurumandala, with the Satya-nārāyaṇa-māhātmya being found in the Revā Khaṇḍa of the Gurumandala edition but not in the Venkateshwar Press edition. [13]

According to Stewart, Satya Nārāyaṇa is a 17th or early 18th century Sanskritization of Satya Pīr, whose tales were included in Skanda and Bhaviṣya Purāṇas. However he notes the vernacular Bengali tales have historically enjoyed greater popularity than the Puranic accounts, and form a literary compendium larger than any other medieval Bengali subject save Gaudiya Vaishnavism. He states the most common stories surrounding Satya Pīr are that of the Brahmin, woodcutter, and merchant and that worship to a vindictive and generous Satya Pīr through śirṇi or śinni is to be performed for material and miraculous gain. Stewart notes the decline in popularity of Satya Pīr worship among Muslims in the 19th and 20th centuries due to Islamic fundamentalism, which allowed Satya Pīr to be more easily accommodated into classical Vaiṣṇava avatāra theology as an incarnation of Viṣṇu. [14]

According to Stewart, the ritual instructions emerged only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the advent of the printing press in the region in an attempt to Sanskritize the tradition from the aniconic simple offering of śirṇi or śinni (a mixture of rice, sugar, banana, milk, and spices) to a more complicated pūjā. However, ritual instructions form less than 1% of the literary compendium, most of which is devoted to oral public genres of pālā gāna and pāñcālī and the now popular women's household ritual vrata kathā, of which the former are far more diverse in content than the fossilized vrata kathā. Stewart states Satya Pīr literature shares the same themes: "worship Satya Pīr to get rich or be rescued from trouble", but are approached through different narrative codes in which different groups of people oriented Satya Pir to competing structures of authority. Stewart lists three main narrative codes of Satya Pīr: as a Hindu Vaiṣṇava god, as a Muslim moral exemplar, and as a personal spiritual guide. In the Vaiṣṇava narrative, the land is overrun by Yavanas and thus Nārāyaṇa incarnates in the form of a saṁyāsī (the functional equivalent of a fakīr/pīr). The Vaiṣṇava stories follow the general pattern of the story of the brāhmaṇa, the woodcutters, the merchant and his family, and sometimes the king. According to Stewart the most popular versions of these narratives are by the Bengali poets Śaṅkarācārya and Rāmeśvara and were inserted into the Skanda Purāṇa and Bhaviṣya Purāṇa. These tales form the basis of the vrata, and at the turn of the 20th century, there was a conscious effort to Sanskritize the worship by editing the Sanskrit text, eliminating the use of the popular pāñcālī texts, and "correcting" the theology. In the brāhmaṇa's tale, an poor brāhmaṇa from Varanasi is forced to move to the Bengal delta (a region far from the Brahmanical Madhyadeśa lacking many brāhmaṇas) to earn money. He encounters a yavana named Satya Pīr who orders the brāhmaṇa to worship him with śirṇi. The brāhmaṇa initially refuses, but acquiesces when Satya Pīr reveals his true form as Viṣṇu-Satyanārāyaṇa, and the brāhmaṇa instantly becomes rich. In the woodcutter's tale, the local woodcutters observe the miraculous change in fortune of the brāhmāṇa, and so receive instructions in Satya Pīr worship from him. There are some variations in the merchants tale, but the theme remains constant: the merchant must follow up on his promise to worship Satya Pīr in exchange for his protection otherwise disaster ensues. Stewart states the Vaiṣṇava version of the tales seeks to appropriate and domesticate the legendary Satya Pīr to a lower stratum of divinity dominated by women's vratas as someone who can make land habitable and bestow prosperity. [2]

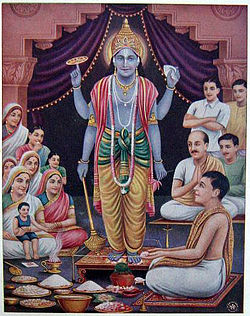

The puja narrates the Satyanarayana Katha (story), which dictates the various worldly and spiritual benefits the puja brings to performers. The Katha states how the deity Narayana vows to aid his devotees during Kali Yuga, the last of the four ages in Hindu cosmology, in particular the performers and attendees of the Satyanarayana Puja. The Katha narrates that the performance of the puja is in itself a promise to God, and recounts the plights of characters who either fail to complete the puja or forget their promises.A ccording to Madhuri Yadlapati, the Satyanarayana Puja is an archetypal example of how "the Hindu puja facilitates the intimacy of devotional worship while enabling a humble sense of participating gratefully in a larger sacred world". [15] According to Vasudha Narayanan, the Satyanarayana vratakathā was likely the most popular vrata among Hindus during the second half of the 20th century. The Vratakathā is recited in Sanskrit or more popularly in vernacular languages and sometimes in English. [16]