Feminist science fiction is a subgenre of science fiction focused on such feminist themes as: gender inequality, sexuality, race, economics, reproduction, and environment. Feminist SF is political because of its tendency to critique the dominant culture. Some of the most notable feminist science fiction works have illustrated these themes using utopias to explore a society in which gender differences or gender power imbalances do not exist, or dystopias to explore worlds in which gender inequalities are intensified, thus asserting a need for feminist work to continue.

Science fiction and fantasy serve as important vehicles for feminist thought, particularly as bridges between theory and practice. No other genres so actively invite representations of the ultimate goals of feminism: worlds free of sexism, worlds in which women's contributions are recognized and valued, worlds that explore the diversity of women's desire and sexuality, and worlds that move beyond gender.

Alice Bradley Sheldon was an American science fiction and fantasy author better known as James Tiptree Jr., a pen name she used from 1967 until her death. It was not publicly known until 1977 that James Tiptree Jr. was a woman. From 1974 to 1985, she also occasionally used the pen name Raccoona Sheldon. Tiptree was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2012.

Sexual themes are frequently used in science fiction or related genres. Such elements may include depictions of realistic sexual interactions in a science fictional setting, a protagonist with an alternative sexuality, a sexual encounter between a human and a fictional extraterrestrial, or exploration of the varieties of sexual experience that deviate from the conventional.

Femininity is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with women and girls. Femininity can be understood as socially constructed, and there is also some evidence that some behaviors considered feminine are influenced by both cultural factors and biological factors. To what extent femininity is biologically or socially influenced is subject to debate. It is conceptually distinct from both the female biological sex and from womanhood, as all humans can exhibit feminine and masculine traits, regardless of sex and gender.

A gynoid, or fembot, is a feminine humanoid robot. Gynoids appear widely in science fiction films and arts. As more realistic humanoid robot design becomes technologically possible, they are also emerging in real-life robot design. Just like any other robot, the main parts of a gynoid include sensors, actuators and a control system. Sensors are responsible for detecting the changes in the environment while the actuators, also called effectors, are motors and other components responsible for the movement and control of the robot. The control system instructs the robot on what to do so as to achieve the desired results.

He, She, and It is a 1991 cyberpunk novel by Marge Piercy. It won the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 1993. The novel's setting is post-apocalyptic America and follows a romance between a human woman and a cyborg created to protect her community from corporate raiders. The novel also interweaves a secondary narrative of the creation of a golem in 17th century Prague. Like Piercy's earlier novel Woman on the Edge of Time (1976), He, She, and It also examines themes such as gender roles, political economy, and environmentalism. In the mid-twenty-first century, Norika is a toxic wasteland. Dominated by powerful corporations known as "multis," the region includes environmental domes, independent "free towns," and the chaotic "Glop," where most Norikans live in violent, polluted conditions ruled by gangs and warlords.

LGBT themes in speculative fiction include lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBTQ) themes in science fiction, fantasy, horror fiction and related genres.[a] Such elements may include an LGBT character as the protagonist or a major character, or explorations of sexuality or gender that deviate from the heteronormative.

Suzy McKee Charnas was an American novelist and short story writer, writing primarily in the genres of science fiction and fantasy. She won several awards for her fiction, including the Hugo Award, the Nebula Award and the James Tiptree Jr. Award. A selection of her short fiction was collected in Stagestruck Vampires and Other Phantasms in 2004. The Holdfast Chronicles, a four-volume story written over the course of almost thirty years was considered to be her major accomplishment in writing. The series addressed the topics of feminist dystopia, separatist societies, war, and reintegration. Another of her major works, The Vampire Tapestry, has been adapted into a play called "Vampire Dreams".

Warm Worlds and Otherwise is a short story collection by American writer Alice Sheldon, first published in 1975 under her pen name James Tiptree Jr. In its introduction, "Who is Tiptree, What is He?", fellow science fiction author Robert Silverberg wrote that he found the theory that Tiptree was female "absurd", and that the author of these stories could only be a man. After Sheldon wrote him that Tiptree was a pseudonym she assumed, Silverberg added a postscript to his introduction in the second edition of the book, published in 1979. According to David Pringle, the collection contains:

Twelve furiously imaginative, occasionally explosive SF stories, the best of which are quite brilliant

Karen Joy Fowler is an American author of science fiction, fantasy, and literary fiction. Her work often centers on the nineteenth century, the lives of women, and social alienation.

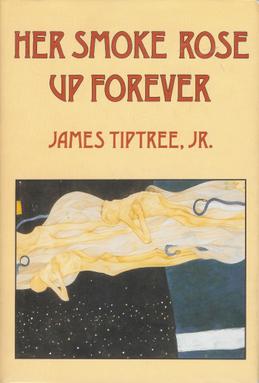

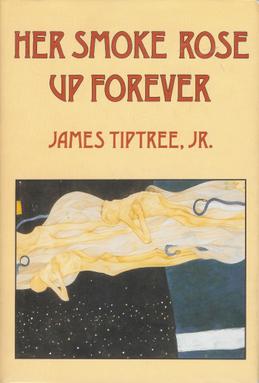

Her Smoke Rose Up Forever is a collection of science fiction and fantasy stories by American author James Tiptree, Jr. It was originally released in 1990 by Arkham House, in an edition of 4,108 copies and was the author's second book published by Arkham House. It was later released to a wider audience in paperback form in 2004 from Tachyon Publications.

Gender has been an important theme explored in speculative fiction. The genres that make up speculative fiction, science fiction, fantasy, supernatural fiction, horror, superhero fiction, science fantasy and related genres, have always offered the opportunity for writers to explore social conventions, including gender, gender roles, and beliefs about gender. Like all literary forms, the science fiction genre reflects the popular perceptions of the eras in which individual creators were writing; and those creators' responses to gender stereotypes and gender roles.

"When It Changed" is a science fiction short story by American writer Joanna Russ. It was first published in the anthology Again, Dangerous Visions.

Bloodchild and Other Stories is the only collection of science fiction stories and essays written by American writer Octavia E. Butler. Each story and essay features an afterword by Butler. "Bloodchild", the title story, won the Hugo Award and Nebula Award. It was first published in 1995. The 2005 expanded edition contains the additional stories "Amnesty" and "The Book of Martha".

The role of women in speculative fiction has changed a great deal since the early to mid-20th century. There are several aspects to women's roles, including their participation as authors of speculative fiction and their role in science fiction fandom. Regarding authorship, in 1948, 10–15% of science fiction writers were female. Women's role in speculative fiction has grown since then, and in 1999, women comprised 36% of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America's professional members. Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley has been called the first science fiction novel, although women wrote utopian novels even before that, with Margaret Cavendish publishing the first in the seventeenth century. Early published fantasy was written by and for any gender. However, speculative fiction, with science fiction in particular, has traditionally been viewed as a male-oriented genre.

"The Women Men Don't See" is a science fiction novelette by American writer Alice Bradley Sheldon, published under the pseudonym James Tiptree, Jr.

"The Matter of Seggri" is a science fiction novelette by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin. It was first published in 1994 in the third issue of Crank!, a science fiction – fantasy anthology, and has since been printed in number of other publications. In 2002, it was published in Le Guin's collection of short stories The Birthday of the World: and Other Stories. "The Matter of Seggri" won the Otherwise Award in 1994 for exploring "gender-bending" and has been nominated for other honors including the Nebula Award.

Rupetta (2013) is a science fiction novel by Australian writer Nike Sulway, who has previously published work under the pseudonym Nicole Bourke. The novel won the 2013 James Tiptree, Jr. Award.

Aurora: Beyond Equality is an anthology of feminist science fiction edited by Vonda N. McIntyre and Susan Janice Anderson and published in 1976.

The battle of the sexes in science fiction is a recurring trope involving conflicts between male and female societies in a science fiction scenario over power.