Interactive map version

Virginia is currently divided into 11 congressional districts, each represented by a member of the United States House of Representatives.

Virginia is currently divided into 11 congressional districts, each represented by a member of the United States House of Representatives.

This is a list of United States representatives from Virginia, their terms, their district boundaries, and the district political ratings according to the CPVI. For the 119th Congress, the state's delegation has a total of 11 members, with 6 Democrats and 5 Republicans.

| Current U.S. representatives from Virginia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Member (Residence) [1] | Party | Incumbent since | CPVI (2025) [2] | District map |

| 1st |  Rob Wittman (Montross) | Republican | December 11, 2007 | R+3 |  |

| 2nd |  Jen Kiggans (Virginia Beach) | Republican | January 3, 2023 | EVEN |  |

| 3rd |  Bobby Scott (Newport News) | Democratic | January 3, 1993 | D+18 |  |

| 4th |  Jennifer McClellan (Richmond) | Democratic | March 7, 2023 | D+17 |  |

| 5th |  John McGuire (Manakin Sabot) | Republican | January 3, 2025 | R+6 |  |

| 6th |  Ben Cline (Fincastle) | Republican | January 3, 2019 | R+12 |  |

| 7th |  Eugene Vindman (Dale City) | Democratic | January 3, 2025 | D+2 |  |

| 8th |  Don Beyer (Alexandria) | Democratic | January 3, 2015 | D+26 |  |

| 9th |  Morgan Griffith (Salem) | Republican | January 3, 2011 | R+22 |  |

| 10th |  Suhas Subramanyam (Ashburn) | Democratic | January 3, 2025 | D+6 |  |

| 11th |  James Walkinshaw (Annandale) | Democratic | September 9, 2025 | D+18 |  |

The apportionment of seats for the House of Representatives between the states is determined following each census. The number of seats to which Virginia has been entitled is as follows:

| 1789 | 1790 | 1800 |

|---|---|---|

| 10 [3] | 19 | 22 |

| 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | 22 | 21 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 9 [4] | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

| 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|

| 11 | 11 |

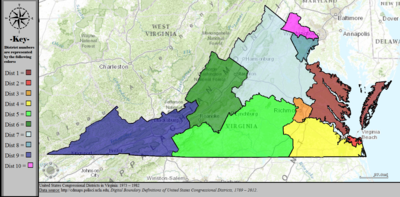

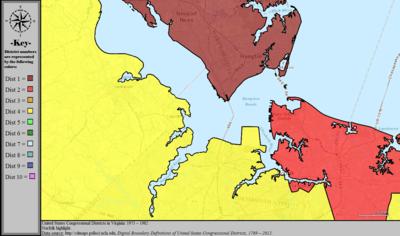

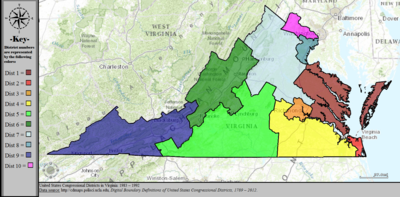

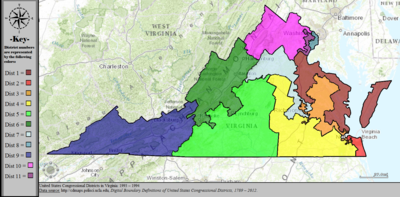

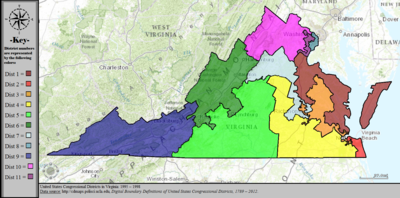

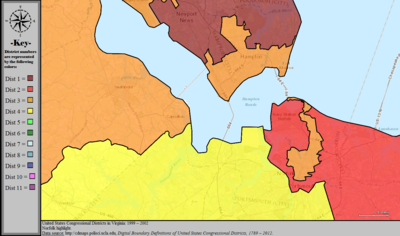

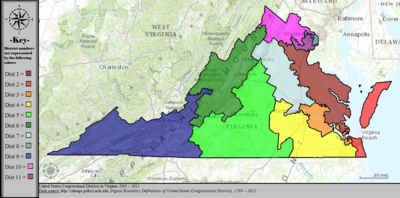

Table of United States congressional district boundary maps in the State of Virginia, are presented chronologically below for the most recent iterations following the redistricting of the 1960s, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that congressional and state legislative districts had to satisfy the one man, one vote criteria for equal representation. The state legislature had long delayed redistricting, leading to outsize influence by rural districts and under-representation of urban areas. [5] All redistricting events that took place in Virginia between 1973 and 2013 are shown.

| Year | Statewide map | Norfolk highlight |

|---|---|---|

| 1973–1982 |  |  |

| 1983–1992 |  |  |

| 1993–1994 |  |  |

| 1995–1998 |  |  |

| 1999–2002 |  |  |

| 2003–2013 |  |  |

| 2013–2017 |  |  |

| 2017–2023 |  |

Virginia pre-2016 congressional districts were ranked the 5th worst in the country by one analysis [6] because counties and cities were broken into multiple pieces to create heavily partisan districts. [7] [ unreliable source? ]

Virginia's congressional districts did not meet the "competitive" mark of a 5% margin of victory, but they averaged a margin of 35%, comparable to the national district statistical average of all 435 districts. Districts 10 and 11 in northern Virginia and the 2nd in the Hampton Roads ranged between 16 and 18%. Virginia, like the nation as a whole, had about 73% of its delegation winning by a margin of 20% or more. Districts 4, 7, 5, 1, and 8 ranged from 22 to 32%, and three outliers had a margin of victory of more than 50%: the 9th district at 48%, the 6th district at 62%, and the 3rd district at 89%. [8]

The Redistricting Coalition of Virginia recommended reforms, including either an independent commission or a bipartisan commission that is not polarized. Member organizations include the League of Women Voters of Virginia, AARP of Virginia, OneVirginia2021, the Virginia Chamber of Commerce, and Virginia Organizing. [9]

The Independent Bipartisan Advisory Commission on Redistricting for the Commonwealth of Virginia made its report on April 1, 2011. It made recommendations for both state legislative and congressional district redistricting, detailing three options for congressional districts, all improving on the 2001 congressional map by reducing the number of split jurisdictions, defining three districts in the DC metro northern Virginia area, and increasing compactness in each district. In accordance with the Voting Rights Act, it maintained one majority African-American district without packing to dilute community influence in other districts. [10]

In 2011, the Virginia College and University Redistricting Competition was organized by professors Michael McDonald of George Mason University and Quentin Kidd of Christopher Newport University. About 150 students on sixteen teams from thirteen schools submitted plans for legislative and U.S. congressional districts. The winning submissions for the congressional redistricting were from the University of Virginia and from the College of William and Mary. The "Division 1" maps conformed to the Governor's Executive Order, and did not address electoral competition or representational fairness. In addition to the criteria of contiguity, equi-population, the federal Voting Rights Act, and communities of interest in the existing city and county boundaries, "Division 2" maps in the competition did incorporate considerations of electoral competition and representational fairness. Judges for the cash award prizes were Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution and Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute. They also created districts more compact than the General Assembly's earlier efforts. [11]

In January 2015, Republican State Senator Jill Holtzman Vogel of the 27th district and Democratic State Senator Louise Lucas of the 18th district sponsored a Senate Joint Resolution to establish additional criteria for the Virginia Redistricting Commission of four identified members of political parties, and three other independent public officials. The criteria began with respecting existing political boundaries, such as cities and towns, counties and magisterial districts, election districts and voting precincts. Districts are to be established on the basis of population, in conformance with federal and state laws and court cases, including those addressing racial fairness. The territory is to be contiguous and compact, without oddly shaped boundaries. The commission is prohibited from using political data or election results to favor either political party or incumbent. It passed with a two-thirds majority of 27 to 12 in the Virginia Senate, and was referred to committee in the House of Delegates. [12]

In November 2020, Virginia's ballot question #1, a constitutional amendment, moved the power to draw legislative districts to a 16-member bipartisan commission made up of eight legislators and eight citizens. [13] [14]

The redistricting of congressional districts prepared by the Virginia legislature, the Virginia General Assembly, in 2012 was used in the 2012 elections and 2014 elections. The redistricting was found unconstitutional and replaced with a court-ordered redistricting on January 16, 2016, before the 2016 elections. [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] Gloria Personhuballah and James Farkas claimed that Virginia's 3rd congressional district violated the Voting Rights Act by packing black voters into the district for the political purpose of making surrounding areas better for Republican candidates. Following Supreme Court precedent, the Eastern District of Virginia Court found that U.S. congressional districts cannot be gerrymandered by race for partisan gain. In this case, the twisting non-contiguous 3rd district hopped the James River in several places and divided multiple locality boundaries, resulting in 89% majorities for black Representative Bobby Scott (D) while surrounding Republican incumbents enjoyed majorities of 16–24%. Subsequent appeals by Republican lawmakers to the Supreme Court were unsuccessful. [20] [8]

On June 17, 2019, the Supreme Court of the United States issued its ruling in Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill, finding that the state House, helmed by Republicans, lacked standing to appeal a lower court order striking down the original legislative district plan as a racial gerrymander.