Related Research Articles

Patanjali was an author, mystic and philosopher in ancient India. He is believed to be an author and compiler of a number of Sanskrit works. The greatest of these are the Yoga Sutras, a classical yoga text. Estimates based on analysis of his works suggests that he may have lived between the 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE. Patanjali is regarded as an avatar of Adi Sesha.

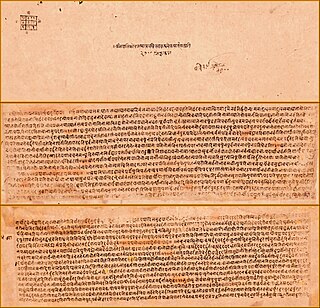

Sanskrit is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late Bronze Age. Sanskrit is the sacred language of Hinduism, the language of classical Hindu philosophy, and of historical texts of Buddhism and Jainism. It was a link language in ancient and medieval South Asia, and upon transmission of Hindu and Buddhist culture to Southeast Asia, East Asia and Central Asia in the early medieval era, it became a language of religion and high culture, and of the political elites in some of these regions. As a result, Sanskrit had a lasting effect on Asian languages.

Linguistics is the scientific study of language, involving analysis of language form, language meaning, and language in context.

Vedic Sanskrit, also simply referred as the Vedic language, is an ancient language of the Indo-Aryan subgroup of the Indo-European language family. It is attested in the Vedas and related literature compiled over the period of the mid-2nd to mid-1st millennium BCE. It is orally preserved, predating the advent of writing by several centuries.

Vṛddhi is a technical term in morphophonology given to the strongest grade in the vowel gradation system of Sanskrit and of Proto-Indo-European. The term is derived from Sanskrit वृद्धि vṛddhi, IPA:[ˈʋr̩d̪ːʱi], lit. 'growth', from Proto-Indo-European *werdʰ- 'to grow'.

The Vedas, sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism.

Shakatayana was a Sanskrit grammarian, linguist, and Vedic scholar. He is known for his theory that all nouns are derived from a verbal root which contrasted to grammarian Pāṇini. He also posited that prepositions only have a meaning when attached to nouns or other words. His theories are presented in his work, Śākaṭāyana-śabdānuśāsana, which is not found in its entirety but referenced by other scholars such as Yāska and Pāṇini.

The Vedanga are six auxiliary disciplines of Hinduism that developed in ancient times and have been connected with the study of the Vedas:

The oral tradition of the Vedas consists of several pathas, "recitations" or ways of chanting the Vedic mantras. Such traditions of Vedic chant are often considered the oldest unbroken oral tradition in existence, the fixation of the Vedic texts (samhitas) as preserved dating to roughly the time of Homer.

Nirukta is one of the six ancient Vedangas, or ancillary science connected with the Vedas – the scriptures of Hinduism. Nirukta covers etymology, and is the study concerned with correct interpretation of Sanskrit words in the Vedas.

Shiksha is a Sanskrit word, which means "instruction, lesson, learning, study of skill". It also refers to one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic studies, on phonetics and phonology in Sanskrit.

Vyākaraṇa refers to one of the six ancient Vedangas, ancillary science connected with the Vedas, which are scriptures in Hinduism. Vyākaraṇa is the study of grammar and linguistic analysis in Sanskrit language.

Mahabhashya, attributed to Patañjali, is a commentary on selected rules of Sanskrit grammar from Pāṇini's treatise, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, as well as Kātyāyana's Vārttika-sūtra, an elaboration of Pāṇini's grammar. It is dated to the 2nd century BCE on the basis of records of Yijing, the Chinese traveller who resided in India for 16 years and studied in Nalanda University.

The grammar of the Sanskrit language has a complex verbal system, rich nominal declension, and extensive use of compound nouns. It was studied and codified by Sanskrit grammarians from the later Vedic period, culminating in the Pāṇinian grammar of the 4th century BCE.

George Cardona is an American linguist, Indologist, Sanskritist, and scholar of Pāṇini. Described as "a luminary" in Indo-European, Indo-Aryan, and Pāṇinian linguistics since the early sixties, Cardona has been recognized as the leading Western scholar of the Indian grammatical tradition (vyākaraṇa) and of the great Indian grammarian Pāṇini. He is currently Professor Emeritus of Linguistics and South Asian Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Cardona was credited by Mohammad Hamid Ansari, the vice president of India, for making the University of Pennsylvania a "center of Sanskrit learning in North America", along with Professors W. Norman Brown, Ludo Rocher, Ernest Bender, Wilhelm Halbfass, and several other Sanskritists.

Pāṇini was a Sanskrit grammarian, logician, philologist, and revered scholar in ancient India, variously dated between the 7th and 4th century BCE.

The Aṣṭādhyāyī is a grammar text that describes a form of the Sanskrit language.

Nighaṇṭu is a Sanskrit term for a traditional collection of words, grouped into thematic categories, often with brief annotations. Such collections share characteristics with glossaries and thesauri, but are not true lexicons, such as the kośa of Sanskrit literature. Particular collections are also called nighaṇṭava.

Sanskrit inherits from its parent, the Proto-Indo-European language, the capability of forming compound nouns, also widely seen in kindred languages, especially German, Greek, and also English.

Sphoṭa is an important concept in the Indian grammatical tradition of Vyakarana, relating to the problem of speech production, how the mind orders linguistic units into coherent discourse and meaning.

References

- 1 2 3 Chatterjee 2020.

- ↑ Witzel 2009.

- ↑ Vergiani 2017, p. 243, n.4.

- ↑ Scharfe 1977, p. 88.

- ↑ Staal 1965, p. 99.

- ↑ Bronkhorst 2016, p. 171.

- ↑ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2013). Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ Bod 2013, p. 14–18.

- ↑ Jha, Girish Nath (2 December 2010). Sanskrit Computational Linguistics: 4th International Symposium, New Delhi, India, December 10-12, 2010. Proceedings. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-17528-2.

- ↑ Sarup, Lakshman (1998). The Nighantu and the Nirukta: The Oldest Indian Treatise on Etymology, Philology and Semantics. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1381-6.

- ↑ Pāṇini; Sumitra Mangesh Katre (1989). Aṣṭādhyāyī of Pāṇini. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. xix–xxi. ISBN 978-81-208-0521-7.

- ↑ Harold G. Coward 1990, p. 4.

- 1 2 Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India's contribution to the study of language . Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-562515-8. LCCN 91174579. OCLC 25096200. Yaska is dealt with in Chapter 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Pinault, Georges-Jean (2000). "Nirukta: Yāska". Corpus de textes linguistiques fondamentaux (in French). Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ↑ Langacker, Ronald W. (1999). Grammar and Conceptualization. Cognitive linguistics research, 14. Berlin; New York: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-016604-0. LCCN 99033328. OCLC 824647882.