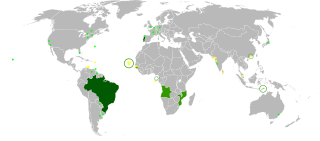

Phonology

Consonants

Like many other accents in Britain, Abercraf's consonants generally follow that of Received Pronunciation, although it does have some unique innovations common for South Wales dialects: [4]

- As in Port Talbot, consonants can be geminated by any preceding vowel except long non-close vowels, and is most noticeable in fortis plosives and when they are in intervocalic positions. [5] [6]

- Strong aspiration for the voiceless plosives /p, t, k/ as [pʰʰ, tʰʰ, kʰʰ] in stressed syllables when in initial position. [4]

- Regular G-dropping, where the suffix -ing is pronounced as /-ɪn/. [4]

- /r/ is regularly a tapped [ ɾ ]. [4]

- Marginal loan consonants from Welsh /r̥, x, ɬ/ may be used for Welsh proper nouns and expressions, yet [r̥] is often heard in the discourse particle right. [4]

- The -es morphemic suffix in words like goes, tomatoes is often voiceless /s/ instead of /z/ found elsewhere. [4]

- Like with Scottish English, the suffix -ths such as in baths, paths and mouths is rendered as /θs/ instead of /ðz/. [4]

- H-dropping is quite common in informal speech, although /h/ is pronounced in emphatic speech and while reading word lists. [4]

- /l/ is always clear, likewise there is no vowel breaking. [4] [7]

Vowels

Abercraf English is non-rhotic; /r/ is only pronounced before a vowel. Like RP, linking and intrusive R is present in the system. [4] On the other hand, the vowel system varies greatly from RP, unlike its consonants, which is stable in many English accents around the world. [8]

Monophthongs

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | ||

| Close-mid | eː | ɜː | oː | |||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛː | ʌ | |||

| Open | a | aː | ɒ | ɒː | ||

- FLEECE and GOOSE are close to cardinal [ iː ] and [ uː ]. [11]

- The HAPPY vowel is always tense, being analysed as the FLEECE vowel, where conservative RP has the lax [ɪ]. [12]

- NURSE is unrounded and mid [ ɜ̝ː ]. Unlike accents in West Glamorgan which have a rounded [ øː ], Abercraf's realisation is identical to RP; a similar articulation had also been recorded in Myddfai. [13]

- There is no phonemic distinction between STRUT and COMMA, with the merged vowel being realised as open-mid [ ɜ ] in stressed syllables and as mid [ ə ] when unstressed. It is transcribed as /ʌ/ because the stressed allophone is close to RP /ʌ/. [14]

- When unstressed and spelt with an ⟨e⟩, the DRESS vowel is preferred, such as cricket, fastest and movement. Likewise when spelt with ⟨a⟩, it varies from TRAP to STRUT. [15]

- There is no horse–hoarse merger, with the first set pronounced as [ɒː], and the second [oː] respectively. [12]

- Like all accents of Wales, the SQUARE–DRESS, PALM–TRAP and THOUGHT–LOT sets are based more on length rather than vowel quality; creating minimal pairs such as shared–shed, heart–hat and short–shot. [16] [17]

- The SQUARE–DRESS vowels are close to cardinal [ ɛ ]. [18]

- THOUGHT and LOT are close to cardinal [ ɒ ]. In the case of the former, its articulation is considerably more open than the corresponding RP vowel. [11]

- Pairs PALM–TRAP are relatively centralised, although TRAP may approach to the front. [11]

- The trap–bath split is completely absent in Abercraf English unlike other Welsh accents which have lexical exceptions. [12] [19]

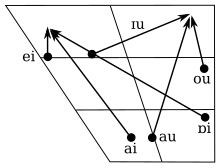

Diphthongs

| Endpoint | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | |||

| Start point | Close | ei | ɪu ou | |

| Open | ai ɒi | au | ||

The offsets of the fronting diphthongs are near-close [ ɪ ], whereas the offsets of the backing diphthongs are close [ u ]. [20]

- The CHOICE onset is closer to open mid [ɔ], despite its transcription as /ɒ/. [18]

- There are no minimal pairs between PRICE words such as aye/I and Dai / Di , unlike in Port Talbot. Like in Myddfai, the onset of PRICE is more open [ ɐ̟ ], compared to other Welsh accents such as West Glamorgan /ə/. [13] [21]

- MOUTH has a near-open onset [ ɐ ], sharing a similar vowel quality as Myddfai, which is also more open than /ə/ that of West Glamorgan. [22]

Abercraf has kept some distinctions between diphthong–monophthong pronunciations; they are shared among other south Welsh dialects such as Port Talbot. These distinctions are lost in most other dialects and they include:

- When GOOSE is spelt with ⟨ew⟩, diphthongal /ɪu/ replaces monophthongal /uː/, thus blew/blue and threw/through are distinct. [23]

- The sequence /juː/ is pronounced as /juː/ when ⟨y⟩ is represented in the spelling, otherwise /ɪu/, as in you/youth as opposed to use/ewe. [23] When unstressed and after non-coronal consonants, /juː/ uses the FOOT vowel instead. [24] [25]

- Absence of toe–tow and pain–pane mergers, therefore there are distinct monophthongal and diphthongal pronunciations of FACE and GOAT lexical sets. They are diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/ when the spelling contains ⟨i⟩/⟨y⟩ and ⟨u⟩/⟨w⟩ respectively, otherwise they are monophthongs /eː/ and /oː/. [23] [26] A good illustration is that of the word play-place/ˈpleipleːs/. [23]

Monophthongal pronunciations /eː/ and /oː/ are both close-mid; they match their cardinal equivalents. The diphthongal pronunciations have less movement compared to other south Welsh accents, with the onsets of each evidently being close-mid. [27] [28] Exceptions to this rule also exist similar to Port Talbot English, but FACE is slightly different in Abercraf: [23]- The monophthong is generally used before nasals and in the sequence ⟨-atiV⟩, therefore strange and patience is pronounced /eː/. [23]

- Certain minimal pairs that are not distinct in Port Talbot English, but are in Abercraf, such as waste/waist. In Port Talbot these two are pronounced monophthongally. [23]

NEAR and CURE are not centring diphthongs unlike RP, rather a disyllabic vowel sequence consisting of the equivalent long vowel as the first element and the COMMA vowel, such that these words are pronounced /niːʌ/ and /kɪuːʌ/ respectively. [23]

- Like Port Talbot English, NEAR has a monosyllabic pronunciation /jøː/ word-initially, including after dropped /h/, making hear, here, year and ear all homophones. Likewise, heard also has this vowel. [4]

Phonemic incidence

Abercraf English generally follows West Glamorgan lexical incidence patterns. [29] [30] [19]

- The first syllable in area may use the FACE vowel instead of SQUARE. [31]

- Only one syllable is in co-op, being homophonous to cop. [31]

- Haulier has the TRAP vowel unlike other accents which have THOUGHT. [31]

- Renowned was once pronounced with [ou], although this is a spelling pronunciation and standard [au] does exist. [32]

- Unstressed to regularly has FOOT over COMMA even before consonants. [15]

- Tooth has the FOOT vowel instead of GOOSE, which shares its pronunciation with the Midlands and Northern England. [31] [19]

- Want has the STRUT vowel, although this pronunciation was known among non-Welsh speakers of English. [31]

- The vowel in whole uses GOOSE instead of the usual GOAT. [31] [19]

Assimilation and elision

As mentioned above, there is less assimilation and elision than in other accents, however some consonants can be elided: [15]

- /n/ is assimilated as /m, ŋ/ in the appropriate environments as RP. Likewise, the /n/ in government is elided. [4]

- Unlike other colloquial accents in Britain, elision alveolar plosives /t, d/ before consonants is not common. /t/ was elided in first job and next week but not in soft wood, on the other hand /d/ is rarely elided in binds and old boy and clearly rendered in could be, headmaster and standard one. [33]

- /s/ is retracted to /ʃ/ before another /ʃ/ as in bus shelter but not before palatal /j/ in this year (see yod-coalescence). [8]

The vowel /ə/ is not elided, thus factory, mandarin, reference always have three syllables, unlike many accents such as RP or even Port Talbot. [15]

Intonation

Abercraf English is considered to have a 'sing-song' or 'lilting' intonation due to having high amount of pitch on an unstressed post-tonic syllable, as well as pre-tonic syllables having a great degree of freedom, with a continuous rising pitch being common. [15]