The Bantu languages are a language family of about 600 languages that are spoken by the Bantu peoples of Central, Southern, Eastern and Southeast Africa. They form the largest branch of the Southern Bantoid languages.

Swahili, also known by its local name Kiswahili, is a Bantu language originally spoken by the Swahili people, who are found primarily in Tanzania, Kenya and Mozambique. The number of current Swahili speakers, be they native or second-language speakers, is estimated to be over 200 million, with Tanzania known to have most of the native speakers.

In linguistics, an elision or deletion is the omission of one or more sounds in a word or phrase. However, these terms are also used to refer more narrowly to cases where two words are run together by the omission of a final sound. An example is the elision of word-final /t/ in English if it is preceded and followed by a consonant: "first light" is often pronounced “firs’ light” Many other terms are used to refer to specific cases where sounds are omitted.

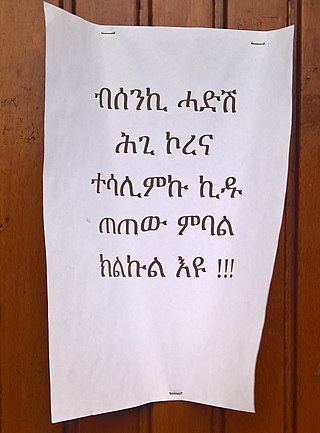

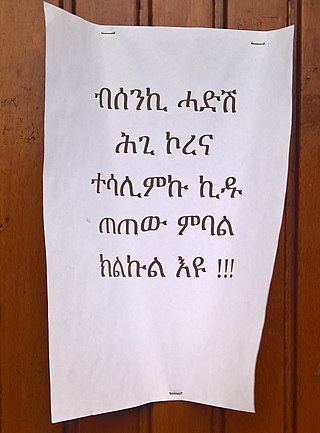

Tigrinya is an Ethiopian Semitic language commonly spoken in Eritrea and in northern Ethiopia's Tigray Region by the Tigrinya and Tigrayan peoples. It is also spoken by the global diaspora of these regions.

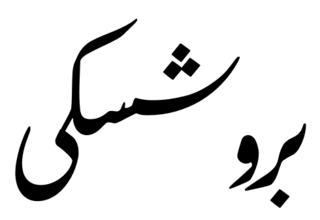

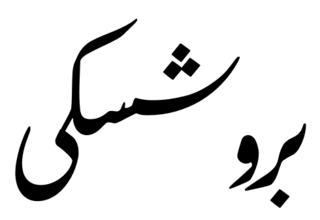

Burushaski is a language isolate, spoken by the Burusho people, who predominantly reside in the northern Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. There are also a few hundred speakers of this language in the northern Jammu and Kashmir, India. In Pakistan, Burushaski is spoken by people in the Hunza District, the Nagar District, the northern Gilgit District, the Yasin Valley in the Gupis-Yasin District and the Ishkoman Valley of the northern Ghizer District. Their native region is located in northern Gilgit–Baltistan. It also borders with the Pamir corridor to the north. In India, Burushaski is spoken in Botraj Mohalla of the Hari Parbat region in Srinagar. It is generally believed that the language was spoken in a much wider area in the past. It is also known as Werchikwar and Miśa:ski.

Plautdietsch or Mennonite Low German is a Low Prussian dialect of East Low German with Dutch influence that developed in the 16th and 17th centuries in the Vistula delta area of Royal Prussia. The word Plautdietsch translates to "flat German". In other Low German dialects, the word for Low German is usually realised as Plattdütsch/Plattdüütsch or Plattdüütsk, but the spelling Plautdietsch is used to refer specifically to the Vistula variant of the language.

Kisuba, also known as Olusuba, is a Bantu language spoken by the Suba people of Kenya. The language features an extensive noun-classification system using prefixes that address gender and number. Suba clans are located on the eastern shore and islands of Lake Victoria in Kenya and Tanzania. They have formed alliances with neighboring clans, such as the Luo people, via intermarriages, and as a result a majority of Suba people are bilingual in Dholuo. The Suba religion has an ancient polytheistic history that includes writings of diverse, ancestral spirits. A recent revival of the Suba language and its culture has influenced the increasing number of native speakers each year.

Yaqui, locally known as Yoeme or Yoem Noki, is a Native American language of the Uto-Aztecan family. It is spoken by about 20,000 Yaqui people, in the Mexican state of Sonora and across the border in Arizona in the United States. It is partially intelligible with the Mayo language, also spoken in Sonora, and together they are called Cahitan languages.

The Gusii language is a Bantu language spoken in Kisii and Nyamira counties in Nyanza Kenya, whose headquarters is Kisii Town,. It is spoken natively by 2.2 million people, mostly among the Abagusii. Ekegusii has only two dialects: The Rogoro and Maate dialects. Phonologically, they differ in the articulation of /t/. Most of the variations existing between the two dialects are lexical. The two dialects can refer to the same object or thing using different terms. An example of this is the word for cat. While one dialect calls a cat ekemoni, the other calls it ekebusi. Another illustrating example can be found in the word for sandals. While the Rogoro word for sandals is chidiripasi, the Maate dialect word is chitaratara. Many more lexical differences manifest in the language. The Maate dialect is spoken in Tabaka and Bogirango. Most of the other regions use the Rogoro dialect, which is also the standard dialect of Ekegusii.

Kipsigis is part of the Kenyan Kalenjin dialect cluster, It is spoken mainly in Kericho and Bomet counties in Kenya. The Kipsigis people are the most numerous tribe of the Kalenjin in Kenya, accounting for 60% of all Kalenjin speakers. Kipsigis is closely related to Nandi, Keiyo, South Tugen (Tuken), and Cherangany.

Maasai or Maa is an Eastern Nilotic language spoken in Southern Kenya and Northern Tanzania by the Maasai people, numbering about 1.5 million. It is closely related to the other Maa varieties: Samburu, the language of the Samburu people of central Kenya, Chamus, spoken south and southeast of Lake Baringo ; and Parakuyu of Tanzania. The Maasai, Samburu, il-Chamus and Parakuyu peoples are historically related and all refer to their language as ɔl Maa. Properly speaking, "Maa" refers to the language and the culture and "Maasai" refers to the people "who speak Maa".

The Koti language, or Ekoti, is a Bantu language spoken in Mozambique by about 64,200 people. Koti is spoken on Koti Island and is also the major language of Angoche, the capital of the district with the same name in the province of Nampula.

The Dholuo dialect or Nilotic Kavirondo, is a dialect of the Luo group of Nilotic languages, spoken by about 4.2 million Luo people of Kenya and Tanzania, who occupy parts of the eastern shore of Lake Victoria and areas to the south. It is used for broadcasts on Ramogi TV and KBC.

Woleaian is the main language of the island of Woleai and surrounding smaller islands in the state of Yap of the Federated States of Micronesia. Woleaian is a Chuukic language. Within that family, its closest relative is Satawalese, with which it is largely mutually intelligible. Woleaian is spoken by approximately 1700 people. Woleai has a writing system of its own, a syllabary based on the Latin alphabet.

Mzungu, also known as muzungu, mlungu, musungu or musongo, is a Bantu word that means "wanderer" originally pertaining to spirits. The term is currently used in predominantly Swahili speaking nations to refer to foreign people dating back to 18th century. The noun Mzungu or its variants are used in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Comoros, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mayotte, Zambia and in Northern Madagascar dating back to the 18th century.

English is a West Germanic language in the Indo-European language family, whose speakers, called Anglophones, originated in early medieval England. The namesake of the language is the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the island of Great Britain.

Digo (Chidigo) is a Bantu language spoken primarily along the East African coast between Mombasa and Tanga by the Digo people of Kenya and Tanzania. The ethnic Digo population has been estimated at around 360,000, the majority of whom are presumably speakers of the language. All adult speakers of Digo are bilingual in Swahili, East Africa's lingua franca. The two languages are closely related, and Digo also has much vocabulary borrowed from neighbouring Swahili dialects.

Ugandan English, also colloquially referred to as Uglish, is the variety of English spoken in Uganda. Aside from Uglish, other colloquial portmanteau words are Uganglish and Ugandlish (2010).

Rangi or Langi is a Bantu language spoken by the Rangi people of Kondoa District in the Dodoma Region of Central Tanzania. Whilst the language is known as Rangi in English and Kirangi in the dominant Swahili spoken throughout the African Great Lakes, the self-referent term is Kilaangi.

Settla, or Settler Swahili, is a Swahili pidgin mainly spoken in large European settlements in Kenya and Zambia. It was used mainly by native English speaking European colonists for communication with the native Swahili speakers.