Related Research Articles

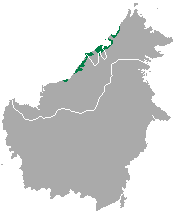

Brunei, formally Brunei Darussalam, is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely surrounded by the Malaysian state of Sarawak. It is separated into two parts by the Sarawak district of Limbang. Brunei is the only sovereign state entirely on Borneo; the remainder of the island is divided between Malaysia and Indonesia. As of 2020, its population was 460,345, of whom about 100,000 live in the capital and largest city, Bandar Seri Begawan. The government is an absolute monarchy ruled by its Sultan, entitled the Yang di-Pertuan, and implements a combination of English common law and sharia, as well as general Islamic practices.

In phonetics, rhotic consonants, or "R-like" sounds, are liquid consonants that are traditionally represented orthographically by symbols derived from the Greek letter rho, including ⟨R⟩, ⟨r⟩ in the Latin script and ⟨Р⟩, ⟨p⟩ in the Cyrillic script. They are transcribed in the International Phonetic Alphabet by upper- or lower-case variants of Roman ⟨R⟩, ⟨r⟩: ⟨r⟩, ⟨ɾ⟩, ⟨ɹ⟩, ⟨ɻ⟩, ⟨ʀ⟩, ⟨ʁ⟩, ⟨ɽ⟩, and ⟨ɺ⟩. Transcriptions for vocalic or semivocalic realisations of underlying rhotics include the ⟨ə̯⟩ and ⟨ɐ̯⟩.

Spoken English shows great variation across regions where it is the predominant language. For example, the United Kingdom has the largest variation of accents of any country in the world, and therefore no single "British accent" exists. This article provides an overview of the numerous identifiable variations in pronunciation; such distinctions usually derive from the phonetic inventory of local dialects, as well as from broader differences in the Standard English of different primary-speaking populations.

Malay is an Austronesian language that is an official language of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, and that is also spoken in East Timor and parts of the Philippines and Thailand. Altogether, it is spoken by 290 million people across Maritime Southeast Asia.

Malaysian English (MyE), formally known as Malaysian Standard English (MySE), is a form of English used and spoken in Malaysia. While Malaysian English can encompass a range of English spoken in Malaysia, some consider to be it distinct from the colloquial form commonly called Manglish. It is quite difficult for native speakers of the English language to understand what is actually being said at times.

Singapore English is the set of varieties of the English language native to Singapore. In Singapore, English is spoken in two main forms: Singaporean Standard English and Singapore Colloquial English.

Hong Kong English is a variety of the English language native to Hong Kong. The variant is either a learner interlanguage or emergent variant, primarily a result of Hong Kong's British overseas territory history and the influence of native Hong Kong Cantonese speakers.

Malaysian Malay, also known as Standard Malay, Bahasa Malaysia, or simply Malay, is a standardized form of the Malay language used in Malaysia and also used in Brunei and Singapore. Malaysian Malay is standardized from the Johore-Riau dialect of Malay. It is spoken by much of the Malaysian population, although most learn a vernacular form of Malay or another native language first. Malay is a compulsory subject in primary and secondary schools.

This chart shows the most common applications of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to represent English language pronunciations.

The Kedayan are an ethnic group residing in Brunei, Federal Territory of Labuan, southwest of Sabah, and north of Sarawak on the island of Borneo. According to the Language and Literature Bureau of Brunei, the Kedayan language is spoken by about 30,000 people in Brunei, and it has been claimed that there are a further 46,500 speakers in Sabah and 37,000 in Sarawak. In Sabah the Kedayan mainly live in the cities of Sipitang, Beaufort, Kuala Penyu and Papar. In Sarawak the Kedayans mostly reside in Lawas, Limbang, Miri and the Subis area.

The culture of Brunei is strongly influenced by Malay cultures and the Islam. The culture is also influenced by the demographic makeup of the country: more than two-thirds of the population are Malay, and the remainder consists of Chinese, Indians and indigenous groups such as Muruts, Dusuns and Kedayans. While Standard Malay is the official language of Brunei, languages such as Brunei Malay and English are more commonly spoken.

There are a number of languages spoken in Brunei. The official language of the state of Brunei is Standard Malay, the same Malaccan dialect that is the basis for the standards in Malaysia and Indonesia. This came into force on 29 September 1959, with the signing of Brunei 1959 Constitution.

Singlish is an English-based creole language spoken in Singapore. Singlish arose out of a situation of prolonged language contact between speakers of many different languages in Singapore, including Hokkien, Malay, Teochew, Cantonese and Tamil.

The Brunei Malay language is the most widely spoken language in Brunei and a lingua franca in some parts of Sarawak and Sabah, such as Labuan, Limbang, Lawas, Sipitang and Papar. Though Standard Malay is promoted as the official national language of Brunei, Brunei Malay is socially dominant and it is currently replacing the minority languages of Brunei, including the Dusun and Tutong languages. It is quite divergent from Standard Malay to the point where it is almost mutually unintelligible with it.

The Tutong language, also known as Basa Tutong, is a language spoken by approximately 17,000 people in Brunei. It is the main language of the Tutong people, the majority ethnic group in the Tutong District of Brunei.

This article explains the phonology of Malay and Indonesian based on the pronunciation of Standard Malay, which is the official language of Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia, and Indonesian, which is the official language of Indonesia and a working language in Timor Leste. There are two main standards for Malay pronunciation, the Johor-Riau standard, used in Brunei and Malaysia, and the Baku, used in Indonesia and Singapore.

Belait, or Lemeting, is a Malayo-Polynesian language of Brunei and neighbouring Malaysia. It is spoken by the Belait people who mainly reside in the Bruneian Belait District. There were estimated to be 700 speakers in 1995.

Rhoticity in English is the pronunciation of the historical rhotic consonant by English speakers. The presence or absence of rhoticity is one of the most prominent distinctions by which varieties of English can be classified. In rhotic varieties, the historical English sound is preserved in all pronunciation contexts. In non-rhotic varieties, speakers no longer pronounce in postvocalic environments—that is, when it is immediately after a vowel and not followed by another vowel. For example, in isolation, a rhotic English speaker pronounces the words hard and butter as /ˈhɑːrd/ and /ˈbʌtər/, whereas a non-rhotic speaker "drops" or "deletes" the sound, pronouncing them as /ˈhɑːd/ and /ˈbʌtə/. When an r is at the end of a word but the next word begins with a vowel, as in the phrase "better apples", most non-rhotic speakers will pronounce the in that position, since it is followed by a vowel in this case.

The Lingua Franca Core (LFC) is a selection of pronunciation features of the English language recommended as a basis in teaching of English as a lingua franca. It was proposed by linguist Jennifer Jenkins in her 2000 book The Phonology of English as an International Language. Jenkins derived the LFC from features found to be crucial in non-native speakers' understanding of each other, and advocated that teachers focus on those features and regard deviations from other native features not as errors but as acceptable variations. The proposal sparked a debate among linguists and pedagogists, while Jenkins contended that much of the criticism was based on misinterpretations of her proposal.

References

- ↑ Clynes, A. (2014). Brunei Malay: An overview. In P. Sercombe, M. Boutin & A. Clynes (Eds.), Advances in research on linguistic and cultural practices in Borneo (pp. 153-200). Phillips, ME: Borneo Research Council.

- ↑ McLellan, J., Noor Azam Haji-Othman, & Deterding, D. (2016). The Language Situation in Brunei Darussalam. In Noor Azam Haji-Othman., J. McLellan & D. Deterding (Eds.), The use and status of language in Brunei Darussalam: A kingdom of unexpected linguistic diversity (pp. 9–16). Singapore: Springer.

- ↑ Lambert, J. (2018). A multitude of ‘lishes’: The nomenclature of hybridity. English World-wide, 39(1), 23. DOI: 10.1075/eww.38.3.04lam

- ↑ Saunders, G. (1994). A History of Brunei. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Hussainmiya, B. A. (1995). Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III: The Making of Brunei Darusslam. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Ishamina Athirah (2017). Brunei Malay. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 47(1), 99–108. On-line Version

- ↑ Clynes, A., & Deterding, D. (2011). Standard Malay (Brunei). Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 41, 259–268. On-line Version Archived 2015-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Martin, P. W., & Poedjoesoedarmo, G. (1996). An overview of the language situation in Brunei Darussalam. In P. W. Martin, A. C. K. Ozog & G. Poedjoesoedarmo (eds.), Language Use and Language Change in Brunei Darussalam (pp. 1–23). Athens, OH: Ohio University Center for International Studies.

- ↑ Jones, G. (1996). The Brunei education policy in Brunei Darussalam. In P. W. Martin, A. C. K. Ozog & G. Poedjoesoedarmo (eds.), Language Use and Language Change in Brunei Darussalam (pp. 123–132). Athens, OH: Ohio University Center for International Studies.

- ↑ Gunn, G. C. (1997). Language, Power, & Ideology in Brunei Darussalam. Athens, OH: Ohio University Center for International Studies. page 155.

- ↑ Jones, G. M. (2012). Language planning in its historical context in Brunei Darussalam. In E. L. Low & Azirah Hashim (Eds.), English in Southeast Asia: Features, Policy and Language in Use (pp. 175–187). Amseterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- ↑ Jones, G. M. (2016). Changing patterns of education in Brunei: How past plans have shaped future trends. In Noor Azam Haji-Othman., J. McLellan & D. Deterding (Eds.), The use and status of language in Brunei Darussalam: A kingdom of unexpected linguistic diversity (pp. 267–278). Singapore: Springer.

- ↑ Noor Azam (2012). It's not always English: "Duelling Aunties" in Brunei Darussalam. In V. Rapatahana & P. Bunce (eds.), English Language as Hydra (pp. 175-190). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- ↑ Coluzzi, P. (2010). Endangered languages in Borneo: a survey among the Iban and Murut (Lun Bawang) in Temburong, Brunei. Oceanic Linguistics, 49(1), 119–143.

- ↑ Wood, A., Henry, A., Malai Ayla Hj Abd., & Clynes, A. (2011). English in Brunei: “She speaks excellent English” – “No he doesn’t”. In L. J. Zhang, R. Rubdy & L. Alsagoff (Eds.), Asian Englishes: Changing Perspectives in a Globalized World (pp. 52–66). Singapore: Pearson.

- ↑ Ishamina Athirah (2011). Identification of Bruneian ethnic groups from their English pronunciation. Southeast Asia, 11, 37–45. On-line Version Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mossop, J. (1996). Some phonological features of Brunei English. In P. W. Martin, A. C. K. Ozog & G. Poedjoesoedarmo (eds.), Language Use and Language Change in Brunei Darussalam (pp. 189–208). Athens, OH: Ohio University Center for International Studies.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 40.

- ↑ Salbrina, S. (2006). The vowels of Brunei English: An acoustic investigation. English World-Wide, 27, 247–264.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 38.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 41.

- ↑ Salbrina, S., & Deterding, D. (2010). Rhoticity in Brunei English. English World-Wide, 31, 121–137.

- ↑ Nur Raihan Mohamad (2017). Rhoticity in Brunei English : A diachronic approach. Southeast Asia, 17, 1-7. PDF Version

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 53.

- ↑ Mesthrie, R., & Bhatt, R. M. (2008). World Englishes: The Study of Linguistic varieties, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 53.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 54.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 56.

- ↑ Ho, D. G. E. (2009). Exponents of politeness in Brunei English. World Englishes, 28, 35–51.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 94.

- ↑ McLellan, J., & Noor Azam H-J. (2012). Brunei English. In E. L. Low & Azirah Hashim (Eds.), English in Southeast Asia: Features, Policy and Language Use (pp. 75-90). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. p. 82.

- ↑ Ishamina Athirah, & Deterding, D. (2017). English medium education in a university in Brunei Darussalam: Code-switching and intelligibility. In I. Walkinshaw, B. Fenton-Smith & P. Humphreys (Eds.), English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific (pp. 281–297). Singapore: Springer.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 101.

- ↑ Deterding, D., & Salbrina S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 99.

- ↑ McLellan, J., & Noor Azam H-J. (2012). Brunei English. In E. L. Low & Azirah Hashim (Eds.), English in Southeast Asia: Features, Policy and Language Use (pp. 75-90). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. p. 83

- ↑ McLellan, J. (2010). Mixed codes or varieties of English. In A. Kirkpatrick (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of World Englishes (pp. 425–441). London/New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Faahirah, R. (2016). Code-switching in Brunei: Evidence from the map task. South East Asia, 16, pp. 65–81. On-line Version

- ↑ Schnieder, E. W. (2007). Postcolonial English: Varieties around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as a Lingua Franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Deterding, D. (2010). Norms for pronunciation in Southeast Asia. World Englishes, 29(3), 364–367.

- ↑ Deterding, D. (2014). The evolution of Brunei English: How it is contributing to the development of English in the world. In S. Buschfeld, T. Hoffmann, M. Huber, & A. Kautzsch (Eds.), The Evolution of Englishes. The Dynamic Model and Beyond (pp. 420–433). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.