Related Research Articles

Canadian English encompasses the varieties of English used in Canada. According to the 2016 census, English was the first language of 19.4 million Canadians or 58.1% of the total population; the remainder spoke French (20.8%) or other languages (21.1%). In the Canadian province of Quebec, only 7.5% of the population are anglophone, as most of Quebec's residents are native speakers of Quebec French.

North American English is the most generalized variety of the English language as spoken in the United States and Canada. Because of their related histories and cultures, plus the similarities between the pronunciations (accents), vocabulary, and grammar of American English and Canadian English, the two spoken varieties are often grouped together under a single category. Canadians are generally tolerant of both British and American spellings, with British spellings of certain words preferred in more formal settings and in Canadian print media; for some other words the American spelling prevails over the British.

Spoken English shows great variation across regions where it is the predominant language. The United Kingdom has a wide variety of accents, and no single "British accent" exists. This article provides an overview of the numerous identifiable variations in pronunciation. Such distinctions usually derive from the phonetic inventory of local dialects, as well as from broader differences in the Standard English of different primary-speaking populations.

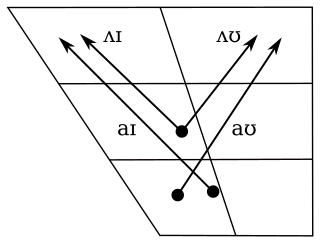

Canadian raising is an allophonic rule of phonology in many varieties of North American English that changes the pronunciation of diphthongs with open-vowel starting points. Most commonly, the shift affects or, or both, when they are pronounced before voiceless consonants. In North American English, and usually begin in an open vowel [~], but through raising they shift to, or. Canadian English often has raising in words with both and, while a number of American English varieties have this feature in but not. It is thought to have originated in Canada in the late 19th century.

The Ottawa Valley is the valley of the Ottawa River, along the boundary between Eastern Ontario and the Outaouais, Quebec, Canada. The valley is the transition between the Saint Lawrence Lowlands and the Canadian Shield. Because of the surrounding shield, the valley is narrow at its western end and then becomes increasingly wide as it progresses eastward. The underlying geophysical structure is the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben. Approximately 1.3 million people reside in the valley, around 80% of whom reside in Ottawa. The total area of the Ottawa Valley is 2.4 million ha. The National Capital Region area has just over 1.4 million inhabitants in both provinces.

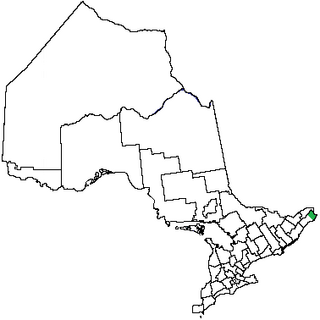

Renfrew County is a county in the Canadian province of Ontario. It stands on the west bank of the Ottawa River. There are 17 municipalities in the county.

Lanark County is a county located in the Canadian province of Ontario. Its county seat is Perth, which was first settled in 1816 and was known as a social and political capital before being over shadowed by what we now know as Ottawa.

Eastern Ontario is a secondary region of Southern Ontario in the Canadian province of Ontario which lies in a wedge-shaped area between the Ottawa River and St. Lawrence River. It shares water boundaries with Quebec to the north and New York State to the east and south, as well as a small land boundary with the Vaudreuil-Soulanges region of Quebec to the east.

Glengarry County, an area covering 288,688 acres (1,168 km2), is a former county in the province of Ontario, Canada. It is historically known for its settlement of Scottish Highlanders. Glengarry County now consists of the modern-day townships of North Glengarry and South Glengarry and it borders the Saint Lawrence River.

Ulster English, also called Northern Hiberno-English or Northern Irish English, is the variety of English spoken in most of the Irish province of Ulster and throughout Northern Ireland. The dialect has been influenced by the Ulster Irish and Scots languages, the latter of which was brought over by Scottish settlers during the Plantation of Ulster and subsequent settlements throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

North-Central American English is an American English dialect, or dialect in formation, native to the Upper Midwestern United States, an area that somewhat overlaps with speakers of the separate Inland Northern dialect situated more in the eastern Great Lakes region. In the United States, it is also known as the Upper Midwestern or North-Central dialect and stereotypically recognized as a Minnesota accent or sometimes Wisconsin accent. It is considered to have developed in a residual dialect region from the neighboring Western, Inland Northern, and Canadian dialect regions.

Canadian Gaelic or Cape Breton Gaelic, often known in Canadian English simply as Gaelic, is a collective term for the dialects of Scottish Gaelic spoken in Atlantic Canada.

North American English regional phonology is the study of variations in the pronunciation of spoken North American English —what are commonly known simply as "regional accents". Though studies of regional dialects can be based on multiple characteristics, often including characteristics that are phonemic, phonetic, lexical (vocabulary-based), and syntactic (grammar-based), this article focuses only on the former two items. North American English includes American English, which has several highly developed and distinct regional varieties, along with the closely related Canadian English, which is more homogeneous geographically. American English and Canadian English have more in common with each other than with varieties of English outside North America.

High Tider, Hoi Toider, or High Tide English is an American English dialect, or family of dialects, spoken in very limited communities of the South Atlantic United States, particularly several small islands and coastal townships. The exact areas include the rural "Down East" region of North Carolina, which encompasses the Outer Banks and Pamlico Sound—specifically Atlantic, Davis, Sea Level, and Harkers Island in eastern Carteret County, the village of Wanchese, and also Ocracoke—plus the Chesapeake Bay, such as Smith Island in Maryland, as well as Guinea Neck and Tangier Island in Virginia. High Tider has been observed as far west as Bertie County, North Carolina; the term is also a local nickname for any native resident of these regions.

Pacific Northwest English is a variety of North American English spoken in the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon, sometimes also including Idaho and the Canadian province of British Columbia. Due to the internal diversity within Pacific Northwest English, current studies remain inconclusive about whether it is best regarded as a dialect of its own, separate from Western American English or even California English or Standard Canadian English, with which it shares its major phonological features. The dialect region contains a highly diverse and mobile population, which is reflected in the historical and continuing development of the variety.

Atlantic Canadian English is a class of Canadian English dialects spoken in Atlantic Canada that is notably distinct from Standard Canadian English. It is composed of Maritime English and Newfoundland English. It was mostly influenced by British and Irish English, Irish and Scottish Gaelic, and some Acadian French. Atlantic Canada is the easternmost region of Canada, comprising four provinces located on the Atlantic coast: Newfoundland and Labrador, plus the three Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Regions such as Miramichi and Cape Breton have a wide variety of phrases and words not spoken outside of their respective regions.

Macanese Portuguese is a Portuguese dialect spoken in Macau, where Portuguese is co-official with Cantonese. Macanese Portuguese is spoken, to some degree either natively or as a second language, by roughly 2.3% of the population of Macau. It should not be confused with Macanese language, a distinct Portuguese creole that developed in Macau during the Portuguese rule.

Older Southern American English is a diverse set of American English dialects of the Southern United States spoken most widely up until the American Civil War of the 1860s, before gradually transforming among its White speakers, first, by the turn of the 20th century, and, again, following the Great Depression, World War II, and, finally, the Civil Rights Movement. By the mid-20th century, among White Southerners, these local dialects had largely consolidated into, or been replaced by, a more regionally unified Southern American English. Meanwhile, among Black Southerners, these dialects transformed into a fairly stable African-American Vernacular English, now spoken nationwide among Black people. Certain features unique to older Southern U.S. English persist today, like non-rhoticity, though typically only among Black speakers or among very localized White speakers.

Midland American English is a regional dialect or super-dialect of American English, geographically lying between the traditionally-defined Northern and Southern United States. The boundaries of Midland American English are not entirely clear, being revised and reduced by linguists due to definitional changes and several Midland sub-regions undergoing rapid and diverging pronunciation shifts since the early-middle 20th century onwards.

References

- 1 2 Cheshire, Jenny. (ed.) 1991. English Around the World: Sociolinguistic Perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press, 134.

- ↑ Labov, William; Sharon Ash; Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English . Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 217, 221. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Padolsky, Enoch and Ian Pringle. 1983. The Linguistic Survey of the Ottawa Valley. American Speech 12, 325–327.

- ↑ Chambers, J. K. "Canada". In: Cheshire, Jenny (1991). English Around the World: Sociolinguistic Perspectives . Cambridge University Press. p. 97.

- ↑ Trudgill, Peter. 2006. Dialect Mixture versus Monogenesis in Colonial Varieties: The Inevitability of Canadian English. The Canadian Journal of Linguistics 51. p. 182.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Henry, Alison. 1992. Infinitives in a For-To Dialect. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 2, 279–283.

- 1 2 Vineberg, Robert. 2010. The Role of Immigration in Ottawa’s Historic Growth and Development: A Multi-City Comparative Analysis of Census and Immigration Data. Ontario: Ottawa Local Immigration Partnership (OLIP), p. 9.

- ↑ The Valley’s Diverse Cultures. http://www.ottawavalleyculture.ca/ottawa-valley-stories/culture-and-hertiage/the-valley-s-diverse-cultures-4337.html. (2014).

- ↑ Vance, Michael E.. 2012. Imperial Immigrants : The Scottish Settlers in the Upper Ottawa Valley, 1815–1840. Toronto: Dundurn, 53.