American English, sometimes called United States English or U.S. English, is the set of varieties of the English language native to the United States. English is the most widely spoken language in the United States and in most circumstances is the de facto common language used in government, education and commerce. It is also the official language of most US states. Since the late 20th century, American English has become the most influential form of English worldwide.

Spoken English shows great variation across regions where it is the predominant language. The United Kingdom has a wide variety of accents, and no single "British accent" exists. This article provides an overview of the numerous identifiable variations in pronunciation. Such distinctions usually derive from the phonetic inventory of local dialects, as well as from broader differences in the Standard English of different primary-speaking populations.

Spanglish is any language variety that results from conversationally combining Spanish and English. The term is mostly used in the United States and refers to a blend of the words and grammar of the two languages. More narrowly, Spanglish can specifically mean a variety of Spanish with heavy use of English loanwords.

Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States. Over 42 million people aged five or older speak Spanish at home. Spanish is also the most learned language other than English, with about 8 million students. Estimates count up to 57 million native speakers, heritage language speakers, and second-language speakers. There is an Academy of the Spanish Language located in the United States as well.

Non-native pronunciations of English result from the common linguistic phenomenon in which non-native speakers of any language tend to transfer the intonation, phonological processes and pronunciation rules of their first language into their English speech. They may also create innovative pronunciations not found in the speaker's native language.

Some of the regional varieties of the Spanish language are quite divergent from one another, especially in pronunciation and vocabulary, and less so in grammar.

Puerto Rican Spanish is the variety of the Spanish language as characteristically spoken in Puerto Rico and by millions of people of Puerto Rican descent living in the United States and elsewhere. It belongs to the group of Caribbean Spanish variants and, as such, is largely derived from Canarian Spanish and Andalusian Spanish. Outside of Puerto Rico, the Puerto Rican accent of Spanish is also commonly heard in the U.S. Virgin Islands and many U.S. mainland cities like Orlando, New York City, Philadelphia, Miami, Tampa, Boston, Cleveland, and Chicago, among others. However, not all stateside Puerto Ricans have knowledge of Spanish. Opposite to island-born Puerto Ricans who primarily speak Spanish, many stateside-born Puerto Ricans primarily speak English, although many stateside Puerto-Ricans are fluent in Spanish and English, and often alternate between the two languages.

The English language as primarily spoken by Hispanic Americans on the East Coast of the United States demonstrates considerable influence from New York City English and African-American Vernacular English, with certain additional features borrowed from the Spanish language. Though not currently confirmed to be a single stabilized dialect, this variety has received some attention in the academic literature, being recently labelled New York Latino English, referring to its city of twentieth-century origin, or, more inclusively, East Coast Latino English. In the 1970s scholarship, the variety was more narrowly called (New York) Puerto Rican English or Nuyorican English. The variety originated with Puerto Ricans moving to New York City after World War I, though particularly in the subsequent generations born in the New York dialect region who were native speakers of both English and often Spanish. Today, it covers the English of many Hispanic and Latino Americans of diverse national heritages, not simply Puerto Ricans, in the New York metropolitan area and beyond along the northeastern coast of the United States.

California English collectively refers to varieties of American English native to California. As California became one of the most ethnically diverse U.S. states, English speakers from a wide variety of backgrounds began to pick up different linguistic elements from one another and also develop new ones; the result is both divergence and convergence within Californian English. However, linguists who studied English before and immediately after World War II tended to find few, if any, patterns unique to California, and even today most California English still basically aligns to a General or Western American accent. Still, certain newer varieties of California English have been gradually emerging since the late 20th century.

An ethnolect is generally defined as a language variety that marks speakers as members of ethnic groups who originally used another language or distinctive variety. According to another definition, an ethnolect is any speech variety associated with a specific ethnic group. It may be a distinguishing mark of social identity, both within the group and for outsiders. The term combines the concepts of an ethnic group and dialect.

In the history of English phonology, there have been many diachronic sound changes affecting vowels, especially involving phonemic splits and mergers. A number of these changes are specific to vowels which occur before, especially in cases where the is at the end of a syllable.

North American English regional phonology is the study of variations in the pronunciation of spoken North American English —what are commonly known simply as "regional accents". Though studies of regional dialects can be based on multiple characteristics, often including characteristics that are phonemic, phonetic, lexical (vocabulary-based), and syntactic (grammar-based), this article focuses only on the former two items. North American English includes American English, which has several highly developed and distinct regional varieties, along with the closely related Canadian English, which is more homogeneous geographically. American English and Canadian English have more in common with each other than with varieties of English outside North America.

New Mexican Spanish refers to the varieties of Spanish spoken in the United States in New Mexico and southern Colorado. It includes a traditional dialect spoken generally by Hispanos—descendants primarily from pre-18th century Spanish-speaking settlers, who live mostly in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado—and a border dialect spoken in southern New Mexico and more reflective of Mexican Spanish.

Barrioization is a theory developed by Chicano scholars Albert Camarillo and Richard Griswold del Castillo to explain the historical formation and maintenance of ethnically segregated neighborhoods of Chicanos and Latinos in the United States. The term was first coined by Camarillo in his book Chicanos in a Changing Society (1979). The process was explained in the context of Los Angeles by Griswold del Castillo in The Los Angeles Barrio, 1850-1890: A Social History (1979). Camarillo defined the term as "the formation of residentially and segregated Chicano barrios or neighbourhoods." The term is used in the field of Human Geography.

Western American English is a variety of American English that largely unites the entire Western United States as a single dialect region, including the states of California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. It also generally encompasses Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, some of whose speakers are classified additionally under Pacific Northwest English.

Texan English is the array of American English dialects spoken in Texas, primarily falling under Southern U.S. English. As one nationwide study states, the typical Texan accent is a "Southern accent with a twist". The "twist" refers to inland Southern U.S., older coastal Southern U.S., and South Midland U.S. accents mixing together, due to Texas's settlement history, as well as some lexical (vocabulary) influences from Mexican Spanish. In fact, there is no single accent that covers all of Texas and few dialect features are unique to Texas alone. The newest and most innovative Southern U.S. accent features are best reported in Lubbock, Odessa, somewhat Houston and variably Dallas, though general features of this same dialect are found throughout the state, with several exceptions: Abilene and somewhat Austin, Corpus Christi, and El Paso appear to align more with Midland U.S. accents than Southern ones.

The sound system of New York City English is popularly known as a New York accent. The New York metropolitan accent is one of the most recognizable accents of the United States, largely due to its popular stereotypes and portrayal in radio, film, and television. Several other common names exist for the accent, associating it with more specific locations in the New York City area, such as a Bronx accent, Brooklyn accent, Queens accent, Long Island accent, or North Jersey accent; however, no research has demonstrated significant linguistic differences between these locations.

Hispanic and Latino Californians are residents of the state of California who are of Hispanic or Latino ancestry. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, Hispanics and Latinos of any race were 39.4% of the state's population, making it the largest ethnicity in California.

The Miami accent is an evolving American English accent or sociolect spoken in South Florida, particularly in Miami-Dade county, originating from central Miami. The Miami accent is most prevalent in American-born Hispanic youth who live in the Greater Miami area.

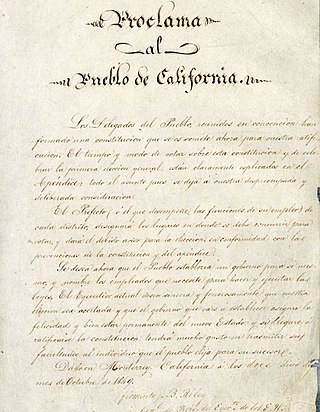

The Spanish language is the most commonly spoken language in California after the English language, spoken by 28.18 percent (10,434,308) of the population. Californian Spanish is a set of varieties of Spanish spoken in California, including the historical variety known as Californio Spanish.