The Goidelic or Gaelic languages form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Manx, also known as Manx Gaelic, is a Gaelic language of the insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, itself a branch of the Indo-European language family. Manx is the historical language of the Manx people.

The music of the Isle of Man reflects Celtic, Norse and other influences, including those from its neighbours, Scotland, Ireland, England and Wales. The Isle of Man is a small island nation in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland.

The culture of the Isle of Man is influenced by its Celtic and, to a lesser extent, its Norse origins, though its close proximity to the United Kingdom, popularity as a UK tourist destination, and recent mass immigration by British migrant workers has meant that British influence has been dominant since the Revestment period. Recent revival campaigns have attempted to preserve the surviving vestiges of Manx culture after a long period of Anglicisation, and significant interest in the Manx language, history and musical tradition has been the result.

On the Isle of Man, longtail is a euphemism used to denote a rat, as a relatively modern superstition has arisen that it is considered bad luck to mention this word. The origins of this superstition date to sea-taboos, where certain words and practices were not mentioned aboard ship, for fear of attracting bad luck.

Literature in the Manx language is known from the 16th century. Early works were often religious in theme, including translations of the Book of Common Prayer, the Bible and Milton's Paradise Lost. Edward Faragher, who published poems, stories and translations, is considered the last major native writer of the language. The historian A. W. Moore collected traditional Manx-language songs and ballads in publications towards the end of the 19th century.

The Manx are a minority ethnic group originating on the Isle of Man, in the Irish Sea in Northern Europe. They belong to the diaspora of the Gaelic ethnolinguistic group, which now populate the parts of the British Isles and Ireland which once were the Kingdom of the Isles and Dál Riata. The Manx are governed through the Tynwald, the legislature of the island, which was introduced by Viking settlers over a thousand years ago. The native mythology and folklores of the Manx belong to the overall Celtic Mythology group, with Manannán mac Lir, the Mooinjer veggey, Buggane, Lhiannan-Shee, Ben-Varrey and the Moddey Dhoo being prominent mythological figures on the island. Their language, Manx Gaelic is derived from Middle Irish, which was introduced by settlers that colonised the island from Gaelic Ireland. However, Manx gaelic later developed in isolation and belongs as a separate Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic languages.

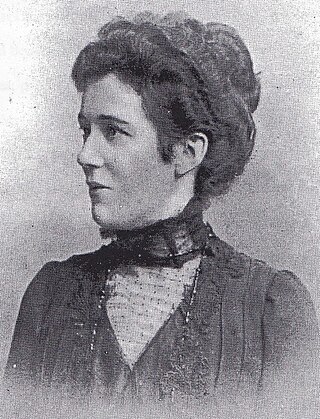

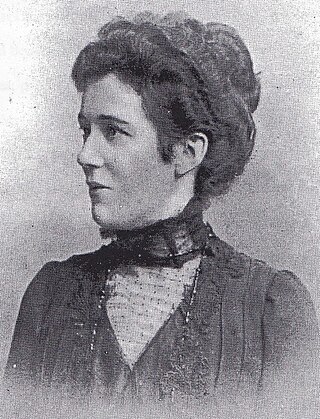

Sophia Morrison was a Manx cultural activist, folklore collector and author. Through her own work and role in encouraging and enthusing others, she is considered to be one of the key figures of the Manx cultural revival. She is best remembered today for writing Manx Fairy Tales, published in 1911, although her greatest influence was as an activist for the revitalisation of Manx culture, particularly through her work with the Manx Language Society and its journal, Mannin, which she edited from 1913 until her death.

Fenodyree in the folklore of the Isle of Man, is a hairy supernatural creature, a sort of sprite or fairy, often carrying out chores to help humans, like the brownies of the larger areas of Scotland and England.

Ellan Vannin is a poem and song, often referred to as "the alternative Manx national anthem", the words of which were written by Eliza Craven Green in 1854 and later set to music by someone called either J. Townsend or F. H. Townend.

Glashtyn is a legendary creature from Manx folklore.

Mooinjer veggey is the Manx for little people, a term used for fairies in Gaelic lore. The equivalent Irish and Scottish Gaelic are Muintir Bheaga and Muinntir Bheaga.

The main language of the Isle of Man is English, predominantly the Manx English dialect. Manx, the historical language of the island, is still maintained by a small speaker population.

Surnames originating on the Isle of Man reflect the recorded history of the island, which can be divided into three different eras — Gaelic, Norse, and English. In consequence most Manx surnames are derived from the Gaelic or Norse languages.

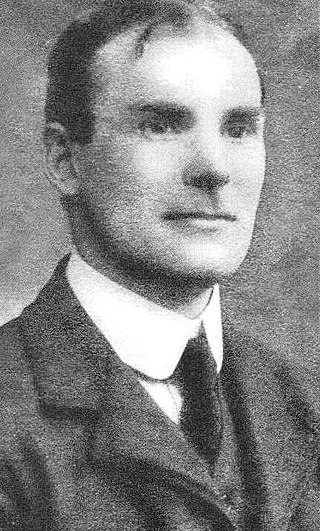

John Joseph Kneen was a Manx linguist and scholar renowned for his seminal works on Manx grammar and on the place names and personal names of the Isle of Man. He is also a significant Manx dialect playwright and translator of Manx poetry. He is commonly best known for his translation of the Manx National Anthem into Manx.

William Walter Gill (1876–1963) was a Manx scholar, folklorist and poet. He is best remembered for his three volumes of A Manx Scrapbook.

Yn Çheshaght Ghailckagh, also known as the Manx Language Society and formerly known as Manx Gaelic Society, was founded in 1899 in the Isle of Man to promote the Manx language. The group's motto is Gyn çhengey, gyn çheer.

Edmund Evans Greaves Goodwin was a Manx language scholar, linguist, and teacher. He is best known for his work First Lessons in Manx that he wrote to accompany the classes he taught in Peel.

Archibald Cregeen was a Manx lexicographer and scholar. He is best known for compiling A Dictionary of the Manks Language (1838), which was the first dictionary for the Manx language to be published.

Doug Fargher also known as Doolish y Karagher or Yn Breagagh, was a Manx language activist, author, and radio personality who was involved with the revival of the Manx language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. He is best known for his English-Manx Dictionary (1979), the first modern dictionary for the Manx language. Fargher was involved in the promotion of Manx language, culture and nationalist politics throughout his life.