American English, sometimes called United States English or U.S. English, is the set of varieties of the English language native to the United States. English is the most widely spoken language in the United States and in most circumstances is the de facto common language used in government, education and commerce. Since the late 20th century, American English has become the most influential form of English worldwide.

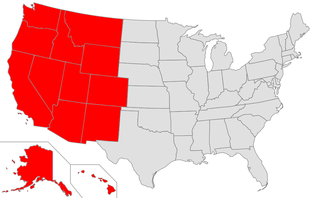

General American English, known in linguistics simply as General American, is the umbrella accent of American English spoken by a majority of Americans, encompassing a continuum rather than a single unified accent. In the United States it is often perceived as lacking any distinctly regional, ethnic, or socioeconomic characteristics, though Americans with high education, or from the North Midland, Western New England, and Western regions of the country are the most likely to be perceived as using General American speech. The precise definition and usefulness of the term continue to be debated, and the scholars who use it today admittedly do so as a convenient basis for comparison rather than for exactness. Other scholars prefer the term Standard American English.

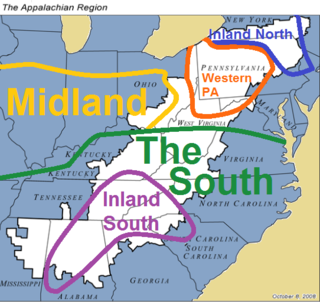

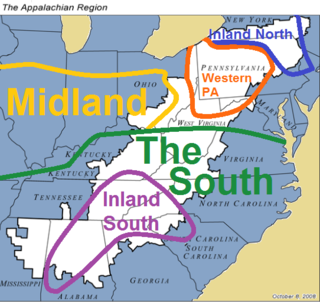

Western Pennsylvania English, known more narrowly as Pittsburgh English or popularly as Pittsburghese, is a dialect of American English native primarily to the western half of Pennsylvania, centered on the city of Pittsburgh, but potentially appearing in some speakers as far north as Erie County, as far west as Youngstown, Ohio, and as far south as Clarksburg, West Virginia. Commonly associated with the working class of Pittsburgh, users of the dialect are colloquially known as "Yinzers".

Southern American English or Southern U.S. English is a regional dialect or collection of dialects of American English spoken throughout the Southern United States, though concentrated increasingly in more rural areas, and spoken primarily by White Southerners. In terms of accent, its most innovative forms include southern varieties of Appalachian English and certain varieties of Texan English. Popularly known in the United States as a Southern accent or simply Southern, Southern American English now comprises the largest American regional accent group by number of speakers. Formal, much more recent terms within American linguistics include Southern White Vernacular English and Rural White Southern English.

A Baltimore accent, also known as Baltimorese, commonly refers to an accent related to Philadelphia English that originates among blue-collar residents of Baltimore, Maryland, United States. It extends into the Baltimore metropolitan area and northeastern Maryland.

Eastern New England English, historically known as the Yankee dialect since at least the 19th century, is the traditional regional dialect of Maine, New Hampshire, and the eastern half of Massachusetts. Features of this variety once spanned an even larger dialect area of New England, for example, including the eastern halves of Vermont and Connecticut for those born as late as the early twentieth century. Studies vary as to whether the unique dialect of Rhode Island technically falls within the Eastern New England dialect region.

California English collectively refers to varieties of American English native to California. As California became one of the most ethnically diverse U.S. states, English speakers from a wide variety of backgrounds began to pick up different linguistic elements from one another and also develop new ones; the result is both divergence and convergence within Californian English. However, linguists who studied English before and immediately after World War II tended to find few, if any, patterns unique to California, and even today most California English still basically aligns to a General or Western American accent. Still, certain newer varieties of California English have been gradually emerging since the late 20th century.

North-Central American English is an American English dialect, or dialect in formation, native to the Upper Midwestern United States, an area that somewhat overlaps with speakers of the separate Inland Northern dialect situated more in the eastern Great Lakes region. In the United States, it is also known as the Upper Midwestern or North-Central dialect and stereotypically recognized as a Minnesota accent or sometimes Wisconsin accent. It is considered to have developed in a residual dialect region from the neighboring Western, Inland Northern, and Canadian dialect regions.

Philadelphia English or Delaware Valley English is a variety or dialect of American English native to Philadelphia and extending into Philadelphia's metropolitan area throughout the Delaware Valley, including southeastern Pennsylvania, counties of northern Delaware, the northern Eastern Shore of Maryland, and all of South Jersey, with the dialect being spoken in cities such as Wilmington, Atlantic City, Camden, Vineland, and Dover. Philadelphia English is one of the best-studied types of English, as Philadelphia's University of Pennsylvania is the home institution of pioneering sociolinguist William Labov. Philadelphia English shares certain features with New York City English and Midland American English, although it remains a distinct dialect of its own. Philadelphia and Baltimore accents together fall under what Labov describes as a single "Mid-Atlantic" regional dialect.

North American English regional phonology is the study of variations in the pronunciation of spoken North American English —what are commonly known simply as "regional accents". Though studies of regional dialects can be based on multiple characteristics, often including characteristics that are phonemic, phonetic, lexical (vocabulary-based), and syntactic (grammar-based), this article focuses only on the former two items. North American English includes American English, which has several highly developed and distinct regional varieties, along with the closely related Canadian English, which is more homogeneous geographically. American English and Canadian English have more in common with each other than with varieties of English outside North America.

The cot–caught merger, also known as the LOT–THOUGHT merger or low back merger, is a sound change present in some dialects of English where speakers do not distinguish the vowel phonemes in words like cot versus caught. Cot and caught is an example of a minimal pair that is lost as a result of this sound change. The phonemes involved in the cot–caught merger, the low back vowels, are typically represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet as and, respectively. The merger is typical of most Canadian and Scottish English dialects as well as some Irish and U.S. English dialects.

Pacific Northwest English is a variety of North American English spoken in the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon, sometimes also including Idaho and the Canadian province of British Columbia. Due to the internal diversity within Pacific Northwest English, current studies remain inconclusive about whether it is best regarded as a dialect of its own, separate from Western American English or even California English or Standard Canadian English, with which it shares its major phonological features. The dialect region contains a highly diverse and mobile population, which is reflected in the historical and continuing development of the variety.

New England English is, collectively, the various distinct dialects and varieties of American English originating in the New England area. Most of eastern and central New England once spoke the "Yankee dialect", some of whose accent features still remain in Eastern New England today, such as "R-dropping". Accordingly, one linguistic division of New England is into Eastern versus Western New England English, as defined in the 1939 Linguistic Atlas of New England and the 2006 Atlas of North American English (ANAE). The ANAE further argues for a division between Northern versus Southern New England English, especially on the basis of the cot–caught merger and fronting. The ANAE also categorizes the strongest differentiated New England accents into four combinations of the above dichotomies, simply defined as follows:

The Canadian Shift is a chain shift of vowel sounds found in Canadian English, beginning among speakers in the last quarter of the 20th century and most significantly involving the lowering and backing of the front vowels. This lowering and backing is structurally identical to the California Shift reported in California English and some younger varieties of Western New England English, Western American English, Pacific Northwest English, and Midland American English; whether the similarly structured shifts in these regional dialects have a single unified cause or not is still not entirely clear. Similar, though not identical, changes to the short front vowels are attested in many English dialects as of 21st-century research, including RP, Indian English, Hiberno-English, South African English, and Australian English.

Inland Northern (American) English, also known in American linguistics as the Inland North or Great Lakes dialect, is an American English dialect spoken primarily by White Americans in a geographic band reaching from the major urban areas of Upstate New York westward along the Erie Canal and through much of the U.S. Great Lakes region. The most distinctive Inland Northern accents are spoken in Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse. The dialect can be heard as far west as eastern Iowa and even among certain demographics in the Twin Cities, Minnesota. Some of its features have also infiltrated a geographic corridor from Chicago southwest along historic Route 66 into St. Louis, Missouri; today, the corridor shows a mixture of both Inland North and Midland American accents. Linguists often characterize the western Great Lakes region's dialect separately as North-Central American English.

Midland American English is a regional dialect or super-dialect of American English, geographically lying between the traditionally-defined Northern and Southern United States. The boundaries of Midland American English are not entirely clear, being revised and reduced by linguists due to definitional changes and several Midland sub-regions undergoing rapid and diverging pronunciation shifts since the early-middle 20th century onwards.

The sound system of New York City English is popularly known as a New York accent. The New York metropolitan accent is one of the most recognizable accents of the United States, largely due to its popular stereotypes and portrayal in radio, film, and television. Several other common names exist for the accent, associating it with more specific locations in the New York City area, such as a Bronx accent, Brooklyn accent, Long Island accent, or North Jersey accent; however, no research has demonstrated significant linguistic differences between these locations.

Standard Canadian English is the largely homogeneous variety of Canadian English that is spoken particularly across Ontario and Western Canada, as well as throughout Canada among urban middle-class speakers from English-speaking families, excluding the regional dialects of Atlantic Canadian English. Canadian English has a mostly uniform phonology and much less dialectal diversity than neighbouring American English. In particular, Standard Canadian English is defined by the cot–caught merger to and an accompanying chain shift of vowel sounds, which is called the Canadian Shift. A subset of the dialect geographically at its central core, excluding British Columbia to the west and everything east of Montréal, has been called Inland Canadian English. It is further defined by both of the phenomena that are known as Canadian raising : the production of and with back starting points in the mouth and the production of with a front starting point and very little glide that is almost in the Canadian Prairies.

Western New England English refers to the varieties of New England English native to Vermont, Connecticut, and the western half of Massachusetts; New York State's Hudson Valley also aligns to this classification. Sound patterns historically associated with Western New England English include the features of rhoticity, the horse–hoarse merger, and the father–bother merger, none of which are features traditionally shared in neighboring Eastern New England English. The status of the cot–caught merger in Western New England is inconsistent, being complete in the north of this dialect region (Vermont), but incomplete or absent in the south, with a "cot–caught approximation" in the middle area.

In the sociolinguistics of the English language, raising or short-a raising is a phenomenon by which the "short a" vowel, the TRAP/BATH vowel, is pronounced with a raising of the tongue. In most American and many Canadian English accents, raising is specifically tensing: a combination of greater raising, fronting, lengthening, and gliding that occurs only in certain words or environments. The most common context for tensing throughout North American English, regardless of dialect, is when this vowel appears before a nasal consonant.