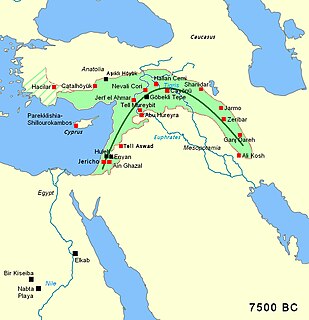

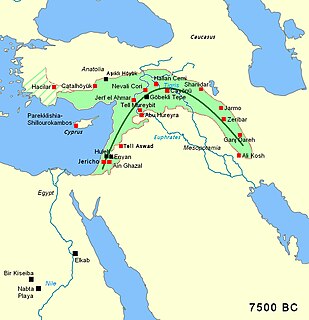

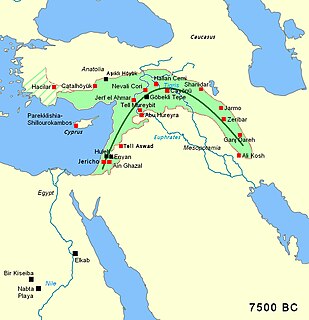

The Neolithic, the final division of the Stone Age, began about 12,000 years ago when the first developments of farming appeared in the Epipalaeolithic Near East, and later in other parts of the world. The Neolithic division lasted until the transitional period of the Chalcolithic from about 6,500 years ago, marked by the development of metallurgy, leading up to the Bronze Age and Iron Age. In other places the Neolithic lasted longer. In Northern Europe, the Neolithic lasted until about 1700 BC, while in China it extended until 1200 BC. Other parts of the world remained broadly in the Neolithic stage of development until European contact.

Amman is the capital and largest city of Jordan and the country's economic, political and cultural centre. With a population of 4,007,526, Amman is the largest city in the Levant region and the sixth-largest city in the Arab world.

Jerash is a city in northern Jordan. The city is the administrative center of the Jerash Governorate, and has a population of 50,745 as of 2015. It is located 48 kilometres (30 mi) north of the capital city Amman.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, in early Levantine and Anatolian Neolithic culture, dating to c. 12,000 – c. 10,800 years ago, that is, 10,000–8,800 BCE. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and Upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia, dating to c. 10,800 – c. 8,500 years ago, that is, 8,800–6,500 BCE. It was typed by Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the West Bank. Like the earlier PPNA people, the PPNB culture developed from the Mesolithic Natufian culture. However, it shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of northeastern Anatolia.

Lime plaster is a type of plaster composed of sand, water, and lime, usually non-hydraulic hydrated lime. Ancient lime plaster often contained horse hair for reinforcement and pozzolan additives to reduce the working time.

Ayn Ghazal is a Neolithic archaeological site located in metropolitan Amman, Jordan, about 2 km north-west of Amman Civil Airport.

The Pottery Neolithic (PN) or Late Neolithic (LN) began around 6,400 BCE in the Fertile Crescent, succeeding the period of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. By then distinctive cultures emerged, with pottery like the Halafian and Ubaid. This period has been further divided into PNA and PNB at some sites.

Aşıklı Höyük is a settlement mound located nearly 1 km south of Kızılkaya village on the bank of the Melendiz brook, and 25 kilometers southeast of Aksaray, Turkey. Aşıklı Höyük is located in an area covered by the volcanic tuff of central Cappadocia, in Aksaray Province. The archaeological site of Aşıklı Höyük was first settled in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, around 8,200 BC.

Jordanian art has a very ancient history. Some of the earliest figurines, found at Aïn Ghazal, near Amman, have been dated to the Neolithic period. A distinct Jordanian aesthetic in art and architecture emerged as part of a broader Islamic art tradition which flourished from the 7th-century. Traditional art and craft is vested in material culture including mosaics, ceramics, weaving, silver work, music, glass-blowing and calligraphy. The rise of colonialism in North Africa and the Middle East, led to a dilution of traditional aesthetics. In the early 20th-century, following the creation of the independent nation of Jordan, a contemporary Jordanian art movement emerged and began to search for a distinctly Jordanian art aesthetic that combined both tradition and contemporary art forms.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) represents the early Neolithic in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent, dating to c. 12,000 – c. 8,500 years ago, that is 10,000-6,500 BCE. It succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipalaeolithic Near East, as the domestication of plants and animals was in its formative stages, having possibly been induced by the Younger Dryas. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture came to an end around the time of the 8.2 kiloyear event, a cool spell centred on 6200 BCE that lasted several hundred years. It is succeeded by the Pottery Neolithic.

The Jordan Archaeological Museum is located in the Amman Citadel of Amman, Jordan. Built in 1951, it presents artifacts from archaeological sites in Jordan, dating from prehistoric times to the 15th century. The collections are arranged in chronological order and include items of everyday life such as flint, glass, metal and pottery objects, as well as more artistic items such as jewelry and statues. The museum also includes a coin collection.

The Zarqa River is the second largest tributary of the lower Jordan River, after the Yarmouk River. It is the third largest river in the region by annual discharge, and its watershed encompasses the most densely populated areas east of the Jordan River. It rises in springs near Amman, and flows through a deep and broad valley into the Jordan, at an elevation 1,090 metres (3,580 ft) lower.

Gary O. Rollefson is an American Anthropologist. He has specialized on Near Eastern prehistoric archeology and prehistoric religion.

The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the archaeological record from early hunter-gatherer societies on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replaced in the Iron Age by the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia brought significant cultural developments, including the oldest examples of writing.

Nahal Hemar Cave is an archeological cave site in Israel, on a cliff in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea and just northwest of Mount Sodom.

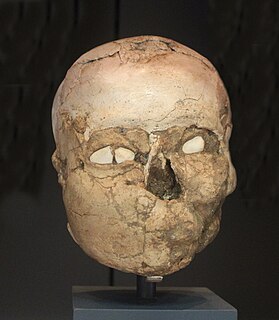

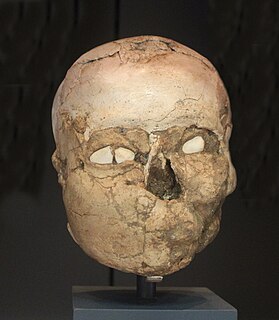

Plastered human skulls are reconstructed human skulls that were made in the ancient Levant between 9,000 and 6,000 BC in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period. They represent some of the oldest forms of art in the Middle East and demonstrate that the prehistoric population took great care in burying their ancestors below their homes. The skulls denote some of the earliest sculptural examples of portraiture in the history of art.

The Jordan Museum is located in Ras Al-Ein district of Amman, Jordan. Built in 2014, the museum is the largest museum in Jordan and hosts the country's most important archaeological findings.

The Urfa man, also known as the Balıklıgöl statue, is an ancient human shaped statue found in excavations in Balıklıgöl near Urfa, in the geographical area of Upper Mesopotamia, in the southeast of modern Turkey. It is dated circa 9000 BC to the period of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, and is considered as "the oldest naturalistic life-sized sculpture of a human". It is considered as contemporaneous with the sites of Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori.

Sha'ar HaGolan is a Neolithic archaeological site near Kibbutz Sha'ar HaGolan in Israel. The type site of the Yarmukian culture, it is notable for the discovery of a significant number of artistic objects, as well as some of the earliest pottery in the Southern Levant.