The 25th century BC comprises the years from 2500 BC to 2401 BC.

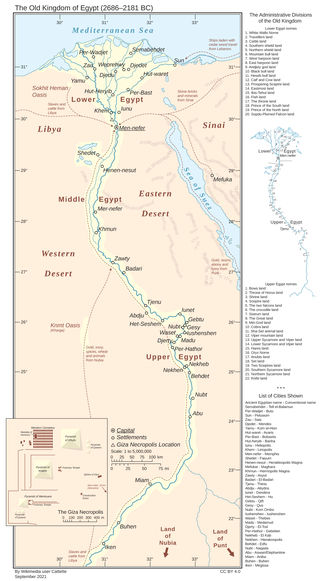

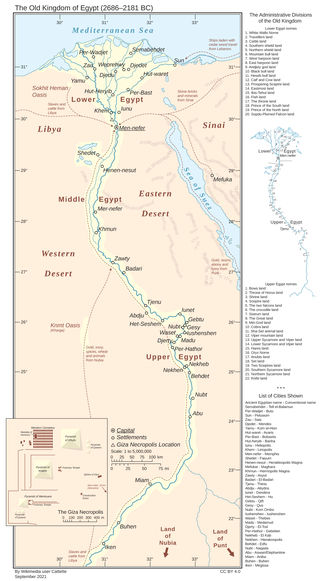

Memphis, or Men-nefer, was the ancient capital of Inebu-hedj, the first nome of Lower Egypt that was known as mḥw ("North"). Its ruins are located in the vicinity of the present-day village of Mit Rahina, in markaz (county) Badrashin, Giza, Egypt.

In ancient Egyptian religion, Apis or Hapis, alternatively spelled Hapi-ankh, was a sacred bull or multiple sacred bulls worshiped in the Memphis region, identified as the son of Hathor, a primary deity in the pantheon of ancient Egypt. Initially, he was assigned a significant role in her worship, being sacrificed and reborn. Later, Apis also served as an intermediary between humans and other powerful deities.

Saqqara, also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English, is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara contains numerous pyramids, including the Pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Pyramid, and a number of mastaba tombs. Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km.

Djoser was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom, and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros and Sesorthos. He was the son of King Khasekhemwy and Queen Nimaathap, but whether he was also the direct successor to their throne is unclear. Most Ramesside king lists identify a king named Nebka as preceding him, but there are difficulties in connecting that name with contemporary Horus names, so some Egyptologists question the received throne sequence. Djoser is known for his step pyramid, which is the earliest colossal stone building in ancient Egypt.

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynasty, such as King Sneferu, under whom the art of pyramid-building was perfected, and the kings Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, who commissioned the construction of the pyramids at Giza. Egypt attained its first sustained peak of civilization during the Old Kingdom, the first of three so-called "Kingdom" periods, which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley.

Khufu or Cheops was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, in the first half of the Old Kingdom period. Khufu succeeded his father Sneferu as king. He is generally accepted as having commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but many other aspects of his reign are poorly documented.

Ancient art refers to the many types of art produced by the advanced cultures of ancient societies with different forms of writing, such as those of ancient China, India, Mesopotamia, Persia, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The art of pre-literate societies is normally referred to as prehistoric art and is not covered here. Although some pre-Columbian cultures developed writing during the centuries before the arrival of Europeans, on grounds of dating these are covered at pre-Columbian art and articles such as Maya art, Aztec art, and Olmec art.

François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette was a French scholar, archaeologist and Egyptologist, and the founder of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities, the forerunner of the Supreme Council of Antiquities.

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculptures, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, architecture, and other art media. It was a conservative tradition whose style changed very little over time. Much of the surviving examples comes from tombs and monuments, giving insight into the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

This is a glossary of ancient Egypt artifacts.

The Department of Ancient Egypt is a department forming an historic part of the British Museum, with Its more than 100,000 pieces making it the largest[h] and most comprehensive collection of Egyptian antiquities outside the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

This page list topics related to ancient Egypt.

The Serapeum of Saqqara was the ancient Egyptian burial place for sacred bulls of the Apis cult at Memphis. It was believed that the bulls were incarnations of the god Ptah, which would become immortal after death as Osiris-Apis, a name which evolved to Serapis (Σέραπις) in the Hellenistic period, and Userhapi (ⲟⲩⲥⲉⲣϩⲁⲡⲓ) in Coptic. It is one of the animal catacombs in the Saqqara necropolis, which also contains the burial vaults of the mother cows of the Apis, the Iseum.

The Stela of Pasenhor, also known as Stela of Harpeson in older literature, is an ancient Egyptian limestone stela dating back to the Year 37 of pharaoh Shoshenq V of the 22nd Dynasty. It was found in the Serapeum of Saqqara by Auguste Mariette and later moved to The Louvre, where it is still.

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt was the last native dynasty of ancient Egypt before the Persian conquest in 525 BC. The dynasty's reign is also called the Saite Period after the city of Sais, where its pharaohs had their capital, and marks the beginning of the Late Period of ancient Egypt.

The Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre is a department of the Louvre that is responsible for artifacts from the Nile civilizations which date from 4,000 BC to the 4th century. The collection, comprising over 50,000 pieces, is among the world's largest, overviews Egyptian life spanning Ancient Egypt, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, Coptic art, and the Roman, Ptolemaic, and Byzantine periods.

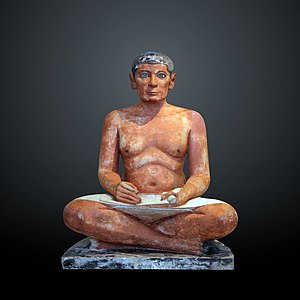

Kaaper or Ka’aper, also commonly known as Sheikh el-Beled, was an ancient Egyptian scribe and priest who lived between the late 4th Dynasty and the early 5th Dynasty. Despite his rank not being among the highest, he is well-known due to his famously fine wooden statue.

The archaeology of ancient Egypt is the study of the archaeology of Egypt, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. Egyptian archaeology is one of the branches of Egyptology.