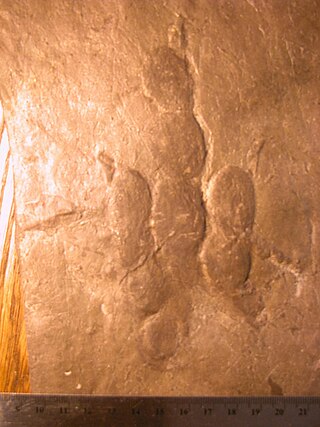

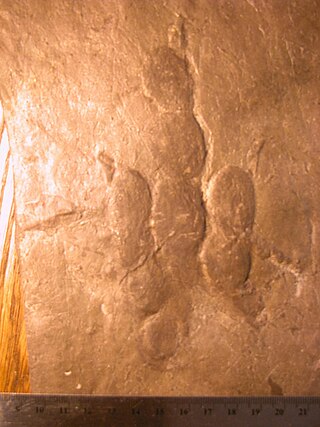

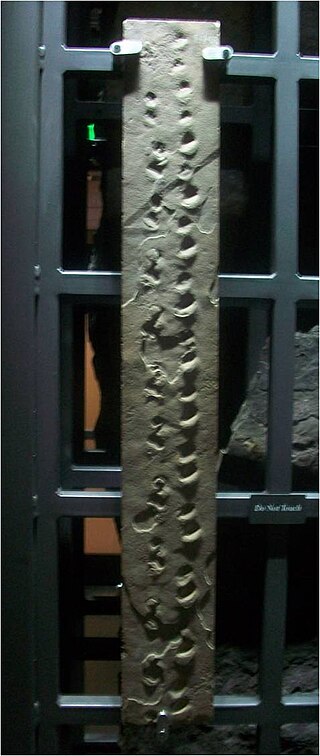

Grallator ["GRA-luh-tor"] is an ichnogenus which covers a common type of small, three-toed print made by a variety of bipedal theropod dinosaurs. Grallator-type footprints have been found in formations dating from the Early Triassic through to the early Cretaceous periods. They are found in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, Brazil and China, but are most abundant on the east coast of North America, especially the Triassic and Early Jurassic formations of the northern part of the Newark Supergroup. The name Grallator translates into "stilt walker", although the actual length and form of the trackmaking legs varied by species, usually unidentified. The related term "Grallae" is an ancient name for the presumed group of long-legged wading birds, such as storks and herons. These footprints were given this name by their discoverer, Edward Hitchcock, in 1858.

Eubrontes is the name of fossilised dinosaur footprints dating from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. They have been identified from France, Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Australia (Queensland), USA, India and China.

Martin G. Lockley is a Welsh palaeontologist. He was educated in the United Kingdom where he obtained degrees and post-doctoral experience in Geology in the 1970s. Since 1980 he has been a professor at the University of Colorado at Denver, (UCD) and is currently a Professor Emeritus. He is best known for work on fossil footprints and was former director of the Dinosaur Tracks Museum at UCD. He is an Associate Curator at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History and Research Associate at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. During his years at UCD he earned a BA in 2007 in Spanish with a minor in Religious Studies, became a member of the Scientific and Medical Network and taught and published on the evolution of consciousness.

The Festningen Sandstone is an Early Cretaceous (Barremian) geologic formation in Svalbard, in the far north of Norway. Fossil ornithopod tracks have been reported from the formation.

Ornithichnites is an ichnotaxon of mammal footprint that was originally classified as a dinosaur. The name was originally used by Edward Hitchcock in 1836 as a higher group name rather than a specific ichnogenus, and thus the name does not have priority over specific ichnogeneric names even if they were first identified as Ornithichnites. Only two ichnospecies exist: O. crassus and O. argenterae.

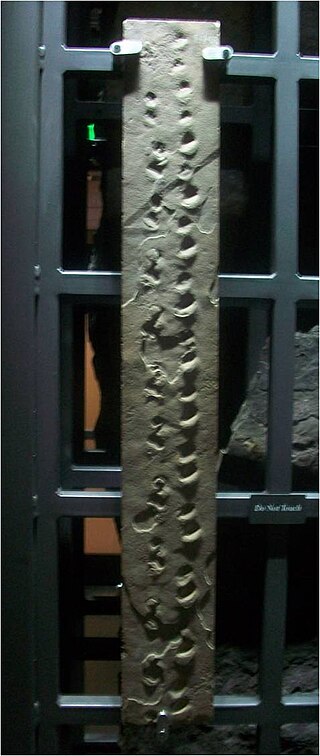

Corncockle Quarry was a large and historically important sandstone quarry near Templand in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. Stone from here was used in the late Victorian era to build tenements in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and also to construct New York 'brownstones'.

Paleontology in Virginia refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Virginia. The geologic column in Virginia spans from the Cambrian to the Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Virginia was covered by a warm shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and nautiloids. The state was briefly out of the sea during the Ordovician, but by the Silurian it was once again submerged. During this second period of inundation the state was home to brachiopods, trilobites and entire reef systems. During the mid-to-late Carboniferous the state gradually became a swampy environment.

Paleontology in Pennsylvania refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The geologic column of Pennsylvania spans from the Precambrian to Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Pennsylvania was submerged by a warm, shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The armored fish Palaeaspis appeared during the Silurian. By the Devonian the state was home to other kinds of fishes. On land, some of the world's oldest tetrapods left behind footprints that would later fossilize. Some of Pennsylvania's most important fossil finds were made in the state's Devonian rocks. Carboniferous Pennsylvania was a swampy environment covered by a wide variety of plants. The latter half of the period was called the Pennsylvanian in honor of the state's rich contemporary rock record. By the end of the Paleozoic the state was no longer so swampy. During the Mesozoic the state was home to dinosaurs and other kinds of reptiles, who left behind fossil footprints. Little is known about the early to mid Cenozoic of Pennsylvania, but during the Ice Age it seemed to have a tundra-like environment. Local Delaware people used to smoke mixtures of fossil bones and tobacco for good luck and to have wishes granted. By the late 1800s Pennsylvania was the site of formal scientific investigation of fossils. Around this time Hadrosaurus foulkii of neighboring New Jersey became the first mounted dinosaur skeleton exhibit at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The Devonian trilobite Phacops rana is the Pennsylvania state fossil.

Paleontology in Massachusetts refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Massachusetts. The fossil record of Massachusetts is very similar to that of neighboring Connecticut. During the early part of the Paleozoic era, Massachusetts was covered by a warm shallow sea, where brachiopods and trilobites would come to live. No Carboniferous or Permian fossils are known from the state. During the Cretaceous period the area now occupied by the Elizabeth Islands and Martha's Vineyard were a coastal plain vegetated by flowers and pine trees at the edge of a shallow sea. No rocks are known of Paleogene or early Neogene age in the state, but during the Pleistocene evidence indicates that the state was subject to glacial activity and home to mastodons. The local fossil theropod footprints of Massachusetts may have been at least a partial inspiration for the Tuscarora legend of the Mosquito Monster or Great Mosquito in New York. Local fossils had already caught the attention of scientists by 1802 when dinosaur footprints were discovered in the state. Other notable discoveries include some of the first known fossil of primitive sauropodomorphs and Podokesaurus. Dinosaur tracks are the Massachusetts state fossil.

Paleontology in Utah refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Utah. Utah has a rich fossil record spanning almost all of the geologic column. During the Precambrian, the area of northeastern Utah now occupied by the Uinta Mountains was a shallow sea which was home to simple microorganisms. During the early Paleozoic Utah was still largely covered in seawater. The state's Paleozoic seas would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, fishes, and trilobites. During the Permian the state came to resemble the Sahara desert and was home to amphibians, early relatives of mammals, and reptiles. During the Triassic about half of the state was covered by a sea home to creatures like the cephalopod Meekoceras, while dinosaurs whose footprints would later fossilize roamed the forests on land. Sand dunes returned during the Early Jurassic. During the Cretaceous the state was covered by the sea for the last time. The sea gave way to a complex of lakes during the Cenozoic era. Later, these lakes dissipated and the state was home to short-faced bears, bison, musk oxen, saber teeth, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. Formally trained scientists have been aware of local fossils since at least the late 19th century. Major local finds include the bonebeds of Dinosaur National Monument. The Jurassic dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis is the Utah state fossil.

Chirotherium, also known as Cheirotherium (‘hand-beast’), is a Triassic trace fossil consisting of five-fingered (pentadactyle) footprints and whole tracks. These look, by coincidence, remarkably like the hands of apes and bears, with the outermost toe having evolved to extend out to the side like a thumb, although probably only functioning to provide a firmer grip in mud. Chirotherium tracks were first found in 1834 in Lower Triassic sandstone (Buntsandstein) in Thuringia, Germany, dating from about 243 million years ago (mya).

The Tensleep Sandstone is a geological formation of Pennsylvanian to very early Permian age in Wyoming.

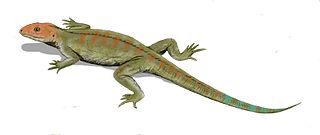

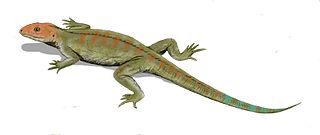

Steganoposaurus is an ichnogenus of fossil reptile footprints. The ichnospecies Steganoposaurus belli, was erected for footprints discovered in Wyoming's Tensleep Sandstone. The find was first reported to the scientific literature by Edward Branson and Maurice Mehl in 1932. This creature was originally presumed to be an amphibian, but the toe prints it left behind were pointed like a reptile's rather than round like an amphibians. The actual trackmaker may have been similar to the genus Hylonomus. The ichnogenus Tridentichnus are similar footprints preserved in the Supai Formation of Arizona.

Tridentichnus is an ichnogenus of fossil footprints. The Tridentichnus trackmaker was a relatively large animal with five toes on its hind feet. They are preserved in the Supai Formation and located in Arizona. The ichnospecies Steganoposaurus belli are similar footprints preserved in the Tensleep Sandstone of Wyoming.

This timeline of ankylosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the ankylosaurs, quadrupedal herbivorous dinosaurs who were protected by a covering bony plates and spikes and sometimes by a clubbed tail. Although formally trained scientists did not begin documenting ankylosaur fossils until the early 19th century, Native Americans had a long history of contact with these remains, which were generally interpreted through a mythological lens. The Delaware people have stories about smoking the bones of ancient monsters in a magic ritual to have wishes granted and ankylosaur fossils are among the local fossils that may have been used like this. The Native Americans of the modern southwestern United States tell stories about an armored monster named Yeitso that may have been influenced by local ankylosaur fossils. Likewise, ankylosaur remains are among the dinosaur bones found along the Red Deer River of Alberta, Canada where the Piegan people believe that the Grandfather of the Buffalo once lived.

The 20th century in ichnology refers to advances made between the years 1900 and 1999 in the scientific study of trace fossils, the preserved record of the behavior and physiological processes of ancient life forms, especially fossil footprints. Significant fossil trackway discoveries began almost immediately after the start of the 20th century with the 1900 discovery at Ipolytarnoc, Hungary of a wide variety of bird and mammal footprints left behind during the early Miocene. Not long after, fossil Iguanodon footprints were discovered in Sussex, England, a discovery that probably served as the inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World.

Chelichnus is an ichnogenus of Permian tetrapod footprint. The name means tortoise traces, because the shape of the prints was originally mistakenly thought to be produced by a tortoise. This is now known to be incorrect, as tortoises did not evolve until much later. It was first found in Corncockle Quarry in Dumfries, Scotland, and described by Rev. Henry Duncan.

This article records new taxa of trace fossils of every kind that are scheduled to be described during the year 2019, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to trace fossil paleontology that are scheduled to occur in the year 2019.

Gwyneddichnium is an ichnogenus from the Late Triassic of North America and Europe. It represents a form of reptile footprints and trackways, likely produced by small tanystropheids such as Tanytrachelos. Gwyneddichnium includes a single species, Gwyneddichnium major. Two other proposed species, G. elongatum and G. minore, are indistinguishable from G. major apart from their smaller size and minor taphonomic discrepancies. As a result, they are considered junior synonyms of G. major.

Protochirotherium, also known as Protocheirotherium, is a Late Permian?-Early Triassic ichnotaxon consisting of five-fingered (pentadactyl) footprints and whole tracks, discovered in Germany and later Morocco, Poland and possibly also Italy. The type ichnospecies is P. wolfhagenense, discovered by R. Kunz in 1999 alongside Chirotherium tracks, was named and described in 2004 and re-evaluated in 2007; a second ichnospecies, P. hauboldi, also exists, which was initially described as an ichnospecies of Brachychirotherium. Protochirotherium-like prints have also been documented from the Late Permian of Italy, possibly representing the oldest known fossils of mesaxonic archosauromorphs.