Seibal, known as El Ceibal in Spanish, is a Classic Period archaeological site of the Maya civilization located in the northern Petén Department of Guatemala, about 100 km SW of Tikal. It was the largest city in the Pasión River region.

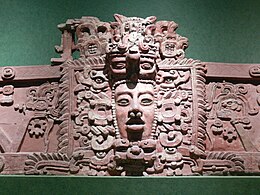

Mesoamerican pyramids form a prominent part of ancient Mesoamerican architecture. Although similar in some ways to Egyptian pyramids, these New World structures have flat tops and stairs ascending their faces. The largest pyramid in the world by volume is the Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the east-central Mexican state of Puebla. The builders of certain classic Mesoamerican pyramids have decorated them copiously with stories about the Hero Twins, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, Mesoamerican creation myths, ritualistic sacrifice, etc. written in the form of Maya script on the rises of the steps of the pyramids, on the walls, and on the sculptures contained within.

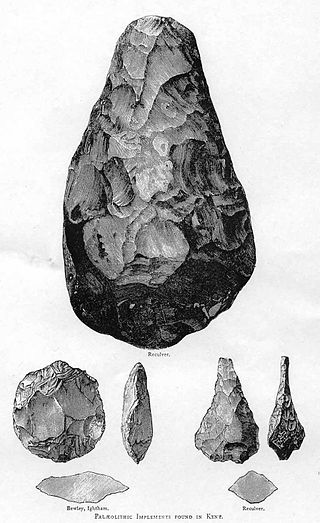

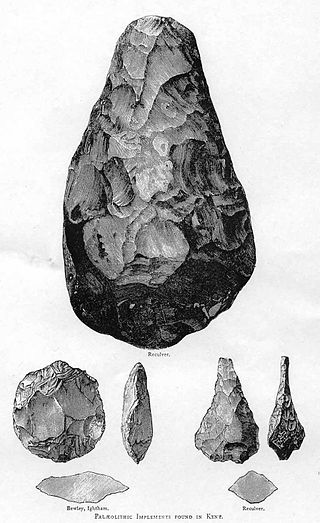

Use-wear analysis is a method in archaeology to identify the functions of artifact tools by closely examining their working surfaces and edges. It is mainly used on stone tools, and is sometimes referred to as "traceological analysis".

Maya society concerns the social organization of the Pre-Hispanic Maya, its political structures, and social classes. The Maya people were indigenous to Mexico and Central America and the most dominant people groups of Central America up until the 6th century.

Trade in Maya civilization was a crucial factor in maintaining Maya cities.

Tamarindito is an archaeological site of the Maya civilization located along an escarpment in the Petén department of Guatemala. The city was the capital of the Petexbatún region of the southwestern Petén during the Early Classic period but was displaced by the newly founded conquest state of Dos Pilas. In the 8th century Tamarindito turned on its new overlord and defeated it. After the destruction of the Dos Pilas kingdom the region descended into chaos and suffered rapid population decline. The city was all but abandoned by the 9th century AD.

La Joyanca is the modern name for a pre-Columbian Maya archaeological site located south of the San Pedro Martir river in the Petén department of Guatemala. It is east of the Maya site of La Florida (Namaan), now the modern town of El Naranjo on the Mexico-Guatemala border. The site was discovered in 1994 during the construction of the Xan-La Libertad oil pipeline in Guatemala. It was immediately recognized as an important, undiscovered Classic period Maya city and became the focus of an archaeological project. Directed by Charlotte Arnauld, Erik Ponciano, and Veronique Breuil, the La Joyanca project conducted excavations here between 1998 and 2003. Several members of this group have continued work at other related locations in the Northwest Peten, including the sites of Zapote Bobal and Pajaral, as part of the Proyecto Peten Noroccidente (PNO).

Nakum is a Mesoamerican archaeological site, and a former ceremonial center and city of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is located in the northeastern portion of the Petén Basin region, in the modern-day Guatemalan department of Petén. The northeastern Petén region contains a good number of other significant Maya sites, and Nakum is one of the three sites forming the Cultural Triangle of "Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo". Nakum is approximately 17 kilometres (10.6 mi) to the north of Yaxha and some 25 kilometres (15.5 mi) to the east of Tikal, on the banks of the Holmul River. Its main features include an abundance of visibly restored architecture, and the roof comb of the site's main temple structure is one of the best-preserved outside Tikal.

Altar de Sacrificios is a ceremonial center and archaeological site of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, situated near the confluence of the Pasión and Salinas Rivers, in the present-day department of Petén, Guatemala. Along with Seibal and Dos Pilas, Altar de Sacrificios is one of the better-known and most intensively-excavated sites in the region, although the site itself does not seem to have been a major political force in the Late Classic period.

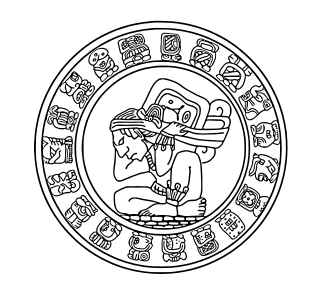

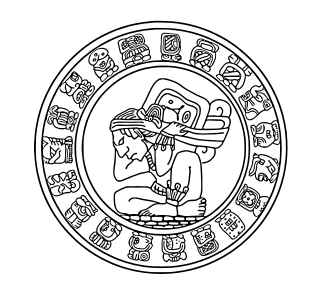

The Maya civilization was a Mesoamerican civilization that existed from antiquity to the early modern period. It is known by its ancient temples and glyphs (script). The Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. The civilization is also noted for its art, architecture, mathematics, calendar, and astronomical system.

Although the Maya were once thought to have been peaceful, current theories emphasize the role of inter-polity warfare as a factor in the development and perpetuation of Maya society. The goals and motives of warfare in Maya culture are not thoroughly understood, but scholars have developed models for Maya warfare based on several lines of evidence, including fortified defenses around structure complexes, artistic and epigraphic depictions of war, and the presence of weapons such as obsidian blades and projectile points in the archaeological record. Warfare can also be identified from archaeological remains that suggest a rapid and drastic break in a fundamental pattern due to violence.

Simon Martin is a British epigrapher, historian, writer and Mayanist scholar. He is best known for his contributions to the study and decipherment of the Maya script, the writing system used by the pre-Columbian Maya civilisation of Mesoamerica. As one of the leading epigraphers active in contemporary Mayanist research, Martin has specialised in the study of the political interactions and dynastic histories of Classic-era Maya polities. Since 2003 Martin has held positions at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology where he is currently an Associate Curator and Keeper in the American Section, while teaching select courses as an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Blue Creek is a riverine system and major archaeological site located in North-Western Belize, Central America. It is situated geographically on the Belize–Mexico border and then continues south across the Guatemala–Mexico border. The river is commonly known as the Río Azul or ‘Azul River’ in Spanish, which translates to ‘blue river’ or ‘blue creek’ in English.

Itzan is a Maya archaeological site located in the municipality of La Libertad in the Petén Department of Guatemala. Various small structures at the site were destroyed in the 1980s during oil exploration activities by Sonpetrol and Basic Resources Ltd, prompting rescue excavations by archaeologists. In spite of its small size, the site appears to have been the most politically important centre in its area, as evidenced by its unusually large quantity of monuments and the size of its major architecture.

Maya cities were the centres of population of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization of Mesoamerica. They served the specialised roles of administration, commerce, manufacturing and religion that characterised ancient cities worldwide. Maya cities tended to be more dispersed than cities in other societies, even within Mesoamerica, as a result of adaptation to a lowland tropical environment that allowed food production amidst areas dedicated to other activities. They lacked the grid plans of the highland cities of central Mexico, such as Teotihuacán and Tenochtitlan. Maya kings ruled their kingdoms from palaces that were situated within the centre of their cities. Cities tended to be located in places that controlled trade routes or that could supply essential products. This allowed the elites that controlled trade to increase their wealth and status. Such cities were able to construct temples for public ceremonies, thus attracting further inhabitants to the city. Those cities that had favourable conditions for food production, combined with access to trade routes, were likely to develop into the capital cities of early Maya states.

Economy is conventionally defined as a function for production and distribution of goods and services by multiple agents within a society and/or geographical place An economy is hierarchical, made up of individuals that aggregate to make larger organizations such as governments and gives value to goods and services. The Maya economy had no universal form of trade exchange other than resources and services that could be provided among groups such as cacao beans and copper bells. Though there is limited archeological evidence to study the trade of perishable goods, it is noteworthy to explore the trade networks of artifacts and other luxury items that were likely transported together.

The history of Maya civilization is divided into three principal periods: the Preclassic, Classic and Postclassic periods; these were preceded by the Archaic Period, which saw the first settled villages and early developments in agriculture. Modern scholars regard these periods as arbitrary divisions of chronology of the Maya civilization, rather than indicative of cultural evolution or decadence. Definitions of the start and end dates of period spans can vary by as much as a century, depending on the author. The Preclassic lasted from approximately 3000 BC to approximately 250 AD; this was followed by the Classic, from 250 AD to roughly 950 AD, then by the Postclassic, from 950 AD to the middle of the 16th century. Each period is further subdivided:

Aguada Fénix is a large Preclassic Mayan ruin located in the state of Tabasco, Mexico, near the border with Guatemala was discovered by aerial survey using laser mapping, and announced in 2020. The flattened mound, nearly a mile in length and between 33 and 50 feet tall, is described as the oldest and the largest Mayan ceremonial site known. The monumental structure is constructed of earth and clay, and is believed to have been built from around 1000 BC to 800 BC.

The Preclassic or Formative Period of Belizean, Maya, and Mesoamerican history began with the Maya development of ceramics during 2000 BC – 900 BC, and ended with the advent of Mayan monumental inscriptions in 250 AD.