Swans are birds of the genus Cygnus within the family Anatidae. The swans' closest relatives include the geese and ducks. Swans are grouped with the closely related geese in the subfamily Anserinae where they form the tribe Cygnini. Sometimes, they are considered a distinct subfamily, Cygninae.

The darters, anhingas, or snakebirds are mainly tropical waterbirds in the family Anhingidae, which contains a single genus, Anhinga. There are four living species, three of which are very common and widespread while the fourth is rarer and classified as near-threatened by the IUCN. The term snakebird is usually used without any additions to signify whichever of the completely allopatric species occurs in any one region. It refers to their long thin neck, which has a snake-like appearance when they swim with their bodies submerged, or when mated pairs twist it during their bonding displays. "Darter" is used with a geographical term when referring to particular species. It alludes to their manner of procuring food, as they impale fishes with their thin, pointed beak. The American darter is more commonly known as the anhinga. It is sometimes called "water turkey" in the southern United States; though the anhinga is quite unrelated to the wild turkey, they are both large, blackish birds with long tails that are sometimes hunted for food.

The Anserinae are a subfamily in the waterfowl family Anatidae. It includes the swans and the true geese. Under alternative systematical concepts, it is split into two subfamilies, the Anserinae contain the geese and the ducks, while the Cygninae contain the swans.

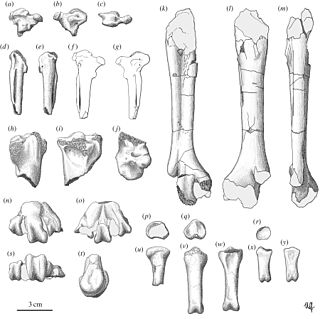

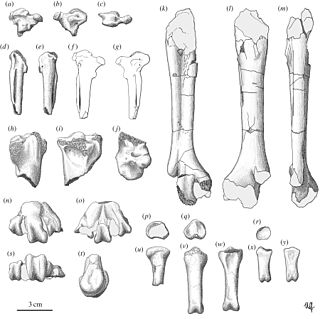

Segnosaurus is a genus of therizinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what is now southeastern Mongolia during the Late Cretaceous, about 102–86 million years ago. Multiple incomplete but well-preserved specimens were discovered in the Gobi Desert in the 1970s, and in 1979 the genus and species Segnosaurus galbinensis were named. The generic name Segnosaurus means "slow lizard" and the specific name galbinensis refers to the Galbin region. The known material of this dinosaur includes the lower jaw, neck and tail vertebrae, the pelvis, shoulder girdle, and limb bones. Parts of the specimens have gone missing or become damaged since they were collected.

Waimanu is a genus of early penguin which lived during the Paleocene, soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, around 62–60 million years ago. It was about the size of an emperor penguin. It is one of the most important bird fossils for understanding the origin and evolution of birds because of the time period it comes from, and the position of penguins near the base of the bird family tree.

Palaelodus is an extinct genus of bird of the Palaelodidae family, distantly related to flamingos. They were slender birds with long, thin legs and a long neck resembling their modern relatives, but likely lived very different livestyles. They had straight, conical beaks not suited for filter feeding and legs showing some similarities to grebes. Their precise lifestyle is disputed, with researchers in the past suggesting they may have been divers, while more recent research suggests they may have used their stiff toes as paddles for swimming while feeding on insect larvae and snails. This behavior may have been key in later phoenicopteriforms developing filterfeeding bills. The genus includes between five and eight species and is found across Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Asia and possibly South America. However some argue that most of the taxa named from Europe simply represent differently sized individuals of one single species. Palaelodus was most abundant during the Late Oligocene to Middle Miocene periods, but isolated remains from Australia indicate that the genus, or at least a relative, survived until the Pleistocene.

Osteodontornis is an extinct seabird genus. It contains a single named species, Osteodontornis orri, which was described quite exactly one century after the first species of the Pelagornithidae was. O. orri was named after the naturalist Ellison Orr (1857-1951).

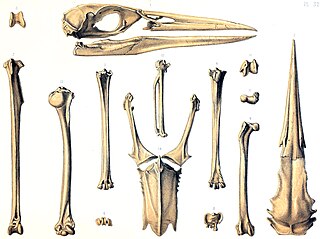

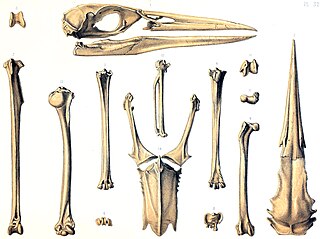

The Rodrigues night heron is an extinct species of heron that was endemic to the Mascarene island of Rodrigues in the Indian Ocean. The species was first mentioned as "bitterns" in two accounts from 1691–1693 and 1725–1726, and these were correlated with subfossil remains found and described in the latter part of the 19th century. The bones showed that the bird was a heron, first named Ardea megacephala in 1873, but moved to the night heron genus Nycticorax in 1879 after more remains were described. The specific name megacephala is Greek for "great-headed". Two related extinct species from the other Mascarene islands have also been identified from accounts and remains: the Mauritius night heron and the Réunion night heron.

Brontornis is an extinct genus of giant bird that inhabited Argentina during the Early to Middle Miocene. Its taxonomic position is highly controversial, with authors alternatively considering it to be a cariamiform, typically a phorusrhacid or an anserimorph.

Copepteryx is an extinct genus of flightless bird of the family Plotopteridae, endemic to Japan during the Oligocene living from 28.4 to 23 mya, meaning it existed for approximately 5.4 million years.

Paraphysornis is an extinct genus of giant flightless terror birds that inhabited Brazil during Late Oligocene or Early Miocene epochs. Although not the tallest phorusrhacid, Paraphysornis was a notably robust bird, having short and robust tarsal bones not suited for pursuit hunting.

Joumocetus is a genus of extinct baleen whale in the family Cetotheriidae containing the single species Joumocetus shimizui. The species is known only from a partial skeleton found in Miocene age sediments of Japan.

This glossary explains technical terms commonly employed in the description of dinosaur body fossils. Besides dinosaur-specific terms, it covers terms with wider usage, when these are of central importance in the study of dinosaurs or when their discussion in the context of dinosaurs is beneficial. The glossary does not cover ichnological and bone histological terms, nor does it cover measurements.

Garganornis is an extinct genus of enormous flightless anatid waterfowl from the Late Miocene of Gargano, Italy. The genus contains one species, G. ballmanni, named by Meijer in 2014. Its enormous size is thought to have been an adaptation to living in exposed, open areas with no terrestrial predators, and as a deterrent to the indigenous aerial predators like the eagle Garganoaetus and the giant barn owl Tyto gigantea.

Caihong is a genus of small paravian theropod dinosaur from China that lived during the Late Jurassic period.

Fukuipteryx is an extinct genus of basal avialan dinosaurs found in Early Cretaceous deposits from Japan's Kitadani Formation. It contains one species, Fukuipteryx prima.

Cascocauda is an extinct genus of anurognathid pterosaur from the Late–Middle Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of Hebei Province, China. The genus contains a single species, C. rong, known from a complete skeleton belonging to a juvenile individual preserved with extensive soft-tissues, including wing membranes and a dense covering of pycnofibres. Some of these pycnofibres appear to be branched, resembling the feathers of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs, and suggesting that pterosaur pycnofibres may be closely related to feathers in dinosaurs.

Giganhinga is a genus of giant darter that lived during the Late Miocene to Early Pleistocene in what is now Uruguay and Argentina. The largest species of anhinga known to science, estimates suggest it may have weighed around 17.7 kg (39 lb) and was likely flightless. Its weight likely helped it dive for prey and the anatomy of the pelvis indicates that it was a good and maneuverable swimmer. Only a single species is currently recognized, G. kiyuensis.

Tonsala is an extinct genus of Plotopteridae, a family of flightless seabird similar in biology with penguins, but more closely related to modern cormorants. The genus is known from terrains dated from the Late Oligocene of the State of Washington and Japan.