The Anatidae are the biological family of water birds that includes ducks, geese, and swans. The family has a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring on all the world's continents except Antarctica. These birds are adapted for swimming, floating on the water surface, and, in some cases, diving in at least shallow water. The family contains around 174 species in 43 genera.

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae, Anseranatidae, and Anatidae, the largest family, which includes over 170 species of waterfowl, among them the ducks, geese, and swans. Most modern species in the order are highly adapted for an aquatic existence at the water surface. With the exception of screamers, males have penises, a trait that has been lost in the Neoaves. Due to their aquatic nature, most species are web-footed.

The magpie goose is the sole living representative species of the family Anseranatidae. This common waterbird is found in northern Australia and southern New Guinea. As the species is prone to wandering, especially when not breeding, it is sometimes recorded outside its core range. The species was once also widespread in southern Australia but disappeared from there largely due to the drainage of the wetlands where the birds once bred. Due to their importance to Aboriginal people as a seasonal food source, as subjects of recreational hunting, and as a tourist attraction, their expansive and stable presence in northern Australia has been "ensured [by] protective management".

Gargano is a historical and geographical sub-region in the province of Foggia, Apulia, southeast Italy, consisting of a wide isolated mountain massif made of highland and several peaks and forming the backbone of the Gargano Promontory projecting into the Adriatic Sea, the "spur" on the Italian "boot".

Island gigantism, or insular gigantism, is a biological phenomenon in which the size of an animal species isolated on an island increases dramatically in comparison to its mainland relatives. Island gigantism is one aspect of the more general "island effect" or "Foster's rule", which posits that when mainland animals colonize islands, small species tend to evolve larger bodies, and large species tend to evolve smaller bodies. This is itself one aspect of the more general phenomenon of island syndrome which describes the differences in morphology, ecology, physiology and behaviour of insular species compared to their continental counterparts. Following the arrival of humans and associated introduced predators, many giant as well as other island endemics have become extinct. A similar size increase, as well as increased woodiness, has been observed in some insular plants such as the Mapou tree in Mauritius which is also known as the "Mauritian baobab" although it is member of the grape family (Vitaceae).

Deinogalerix is an extinct genus of gymnure which lived in Italy in the Late Miocene, 7-10 million years ago. The genus was endemic to what was then the island of Gargano, which is now a peninsula in southeastern Italy bounded by the Adriatic Sea. The first specimens of Deinogalerix were first described in 1972.

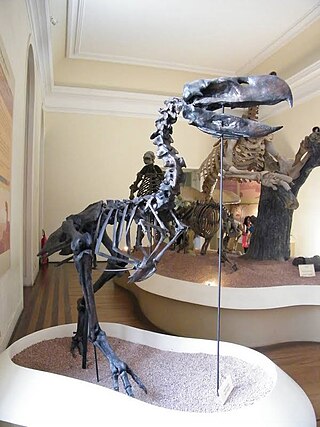

Brontornis is an extinct genus of giant bird that inhabited Argentina during the Early to Middle Miocene. Its taxonomic position is highly controversial, with authors alternatively considering it to be a cariamiform, typically a phorusrhacid or an anserimorph.

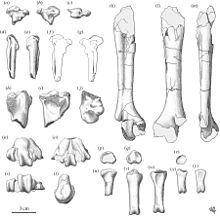

Yungavolucris is a genus of enantiornitheans. It contains the single species Yungavolucris brevipedalis, which lived in the Late Cretaceous. The fossil bones were found in the Lecho Formation at estancia El Brete, Argentina."Yungavolucris brevipedalis" means "Short-footed Yungas bird". The generic name, Yungavolucris is after the Yungas region + the Latin volucris, which translates to "bird". The specific name brevipedalis is from the Latin brevis, which means "short", + pedalis, from the Latin pes, meaning "foot".

The Pelagornithidae, commonly called pelagornithids, pseudodontorns, bony-toothed birds, false-toothed birds or pseudotooth birds, are a prehistoric family of large seabirds. Their fossil remains have been found all over the world in rocks dating between the Early Paleocene and the Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary.

Tyto robusta was a prehistoric barn-owl. It lived at what is now Monte Gargano in Italy, and was an island throughout much of the Neogene when sea levels were higher. The owl's remains date back to the Miocene-Pliocene boundary 5.5 to 5 million years ago. The fossil bones are about 60% as long again as a modern barn owl, giving a total length of about 50–65 cm for T. robusta. This owl provides an interesting case study of evolution and insular gigantism.

Paraphysornis is an extinct genus of giant flightless terror birds that inhabited Brazil during Late Oligocene or Early Miocene epochs. Although not the tallest phorusrhacid, Paraphysornis measured up to 1.4 metres tall at the hips and weighed around 180–240 kilograms (400–530 lb). It was also a notably robust bird, having short and robust tarsal bones not suited for pursuit hunting.

Hoplitomeryx is a genus of extinct deer-like ruminants which lived on the former Gargano Island during the Miocene and the Early Pliocene, now a peninsula on the east coast of South Italy. Hoplitomeryx, also known as "prongdeer", had five horns and sabre-like upper canines similar to a modern musk deer.

Kelenken is a genus of phorusrhacid, an extinct group of large, predatory birds, which lived in what is now Argentina in the middle Miocene about 15 million years ago. The only known specimen was discovered by high school student Guillermo Aguirre-Zabala in Comallo, in the region of Patagonia, and was made the holotype of the new genus and species Kelenken guillermoi in 2007. The genus name references a spirit in Tehuelche mythology, and the specific name honors the discoverer. The holotype consists of one of the most complete skulls known of a large phorusrhacid, as well as a tarsometatarsus lower leg bone and a phalanx toe bone. The discovery of Kelenken clarified the anatomy of large phorusrhacids, as these were previously much less well known. The closest living relatives of the phorusrhacids are the seriemas. Kelenken was found to belong in the subfamily Phorusrhacinae, along with for example Devincenzia.

Eremopezus is a prehistoric bird genus, possibly a palaeognath. It is known only from the fossil remains of a single species, the huge and presumably flightless Eremopezus eocaenus. This was found in Upper Eocene Jebel Qatrani Formation deposits around the Qasr el Sagha escarpment, north of the Birket Qarun lake near Faiyum in Egypt. The rocks its fossils occur in were deposited in the Priabonian, with the oldest dating back to about 36 million years ago (Ma) and the youngest not less than about 33 Ma.

Leptoptilos robustus is an extinct species of large-bodied stork belonging to the genus Leptoptilos that lived on the island of Flores in Indonesia during the Pleistocene epoch. It stood at about 180 cm tall and weighed up to an estimated 16 kg (35 lb). The majority of the discoveries are concentrated in Liang Bua cave located slightly north of Ruteng in the East Nusa Tenggara province.

Bradley Curtis Livezey was an American ornithologist with scores of publications. His main research included the evolution of flightless birds, the systematics of birds, and the ecology and behaviour of steamer ducks.

Wilaru is an extinct genus of presbyornithid bird from Australia during the Late Oligocene to Early Miocene, around 26-22 million years ago. The type species is Wilaru tedfordi, and the second species is Wilaru prideauxi.

Bambolinetta lignitifila is a fossil species of waterfowl from the Late Miocene of Italy, now classified as the sole member of the genus Bambolinetta. First described in 1884 as a typical dabbling duck, it was not revisited until 2014, when a study showed it to be a highly unusual duck species, probably a flightless, wing-propelled diver similar to a penguin.

The Odontoanserae is a proposed clade that includes the family Pelagornithidae and the clade Anserimorphae. The placement of the pseudo-toothed birds in the evolutionary tree of birds has been problematic, with some supporting the placement of them near the orders Procellariformes and Pelecaniformes based on features in the sternum.

Annakacygna is a genus of flightless marine swan from the Miocene of Japan. Named in 2022, Annakacygna displays a series of unique adaptations setting it apart from any other known swan, including a filter feeding lifestyle, a highly mobile tail and wings that likely formed a cradle for their hatchlings in a fashion similar to modern mute swans. Additionally, it may have used both wings and tail as a form of display. All of these traits combined have led the researchers working on it to dub it "the ultimate bird". Two species are known, A. hajimei, which was approximately the size of a black swan, and A. yoshiiensis which exceeded the mute swan in both size and weight. The describing authors proposed the vernacular name Annaka short-winged swan for the genus.