Immune response

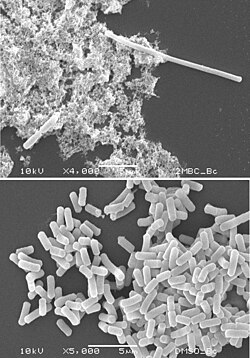

Some of the strategies for bacteria to bypass host defenses include the generation of filamentous structures. As it has been observed in other organisms (such as fungi), filamentous forms are resistant to phagocytosis. As an example of this, during urinary tract infection, filamentous structures of uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) start to develop in response to host innate immune response (more exactly in response to Toll-like receptor 4-TLR4). TLR-4 is stimulated by the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and recruits neutrophils (PMN) which are important leukocytes to eliminate these bacteria. Adopting filamentous structures, bacteria resist these phagocytic cells and their neutralizing activity (which include antimicrobial peptides, degradative enzyme and reactive oxygen species). It is believed that filamentation is induced as a response of DNA damage (by the mechanisms previously exposed), participating SulA mechanism and additional factors. Furthermore, the length of the filamentous bacteria could have a stronger attachment to the epithelial cells, with an increased number of adhesins participating in the interaction, making even harder the work for (PMN). The interaction between phagocyte cells and adopting filamentous-shape bacteria provide an advantage to their survival. In this relate, filamentation could be not only a virulence, but also a resistance factor in these bacteria. [5]

Predator protist

Bacteria exhibit a high degree of "morphological plasticity" that protects them from predation. Bacterial capture by protozoa is affected by size and irregularities in shape of bacteria. Oversized, filamentous, or prosthecate bacteria may be too large to be ingested. On the other hand, other factors such as extremely tiny cells, high-speed motility, tenacious attachment to surfaces, formation of biofilms and multicellular conglomerates may also reduce predation. Several phenotypic features of bacteria are adapted to escape protistan-grazing pressure. [10] [11]

Protistan grazing or bacterivory is a protozoan feeding on bacteria. It affects prokaryotic size and the distribution of microbial groups. There are several feeding mechanisms used to seek and capture prey, because the bacteria have to avoid being consumed from these factors. There are six feeding mechanisms listed by Kevin D. Young. [2]

- Filter feeding: transport water through a filter or sieve

- Sedimentation: allows prey to settle into a capture device

- Interception: capture by predator-induced current or motility and phagocytosis

- Raptorial: predator craws and ingests prey through pharynx or by pseudopods

- Pallium: prey engulfed e.g. by extrusion of feeding membrane

- Myzocytosis: punctures prey and suck out cytoplasm and content

Bacterial responses are elicited depending on the predator and prey combinations because feeding mechanisms differ among the protists. Moreover, the grazing protists also produce the by-products, which directly lead to the morphological plasticity of prey bacteria. For example, the morphological phenotypes of Flectobacillus spp. were evaluated in the presence and absence of the flagellate grazer Orchromonas spp. in a laboratory that has environmental control within a chemostat. Without grazer and with adequate nutrient supply, the Flectobacillus spp. grew mainly in medium-sized rod (4-7 μm), remaining a typical 6.2 μm in length. With the predator, the Flectobacillus spp. size was altered to an average 18.6 μm and it is resistant to grazing. If the bacteria are exposed to the soluble by-products produced by grazing Orchromonas spp. and pass through a dialysis membrane, the bacterial length can increase to an average 11.4 μm. [12] Filamentation occurs as a direct response to these effectors that are produced by the predator and there is a size preference for grazing that varies for each species of protist. [1] The filamentous bacteria that are larger than 7 μm in length are generally inedible by marine protists. This morphological class is called grazing resistant. [13] Thus, filamentation leads to the prevention of phagocytosis and killing by predator. [1]

Bimodal effect

Bimodal effect is a situation that bacterial cell in an intermediate size range are consumed more rapidly than the very large or the very small. The bacteria, which are smaller than 0.5 μm in diameter, are grazed by protists four to six times less than larger cells. Moreover, the filamentous cells or cells with diameters greater than 3 μm are often too large to ingest by protists or are grazed at substantially lower rates than smaller bacteria. The specific effects vary with the size ratio between predator and prey. Pernthaler et al. classified susceptible bacteria into four groups by rough size. [14]

- Bacterial size < 0.4 μm were not grazed well

- Bacterial size between 0.4 μm and 1.6 μm were "grazing vulnerable"

- Bacterial size between 1.6 μm and 2.4 μm were "grazing suppressed"

- Bacterial size > 2.4 μm were "grazing resistant"

Filamentous preys are resistant to protist predation in a number of marine environments. In fact, there is no bacterium entirely safe. Some predators graze the larger filaments to some degree. Morphological plasticity of some bacterial strains is able to show at different growth conditions. For instance, at enhanced growth rates, some strains can form large thread-like morphotypes. While filament formation in subpopulations can occur during starvation or at suboptimal growth conditions. These morphological shifts could be triggered by external chemical cues that might be released by the predator itself. [11]

Besides bacterial size, there are several factors affecting the predation of protists. Bacterial shape, the spiral morphology may play a defensive role towards predation feedings. For example, Arthrospira may reduce its susceptibility to predation by altering its spiral pitch. This alteration inhibits some natural geometric feature of the protist's ingestion apparatus. Multicellular complexes of bacterial cells also change the ability of protist's ingestion. Cells in biofilms or microcolonies are often more resistant to predation. For instance, the swarm cells of Serratia liquefaciens resist predation by its predator, Tetrahymenu. Due to the normal-sized cells that first contact a surface are most susceptible, [15] bacteria need elongating swarm cells to protect them from predation until the biofilm matures. [16] For aquatic bacteria, they can produce a wide range of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), which comprise protein, nucleic acids, lipids, polysaccharides and other biological macromolecules. EPS secretion protects bacteria from HNF grazing. The EPS-producing planktonic bacteria typically develop subpopulations of single cells and microcolonies that are embedded in an EPS matrix. The larger microcolonies are also protected from flagellate predation because of their size. The shift to the colonial type may be a passive consequence of selective feeding on single cells. However, the microcolony formation can be specifically induced in the presence of predators by cell-cell communication (quorum sensing). [15]

As for bacterial motility, the bacteria with high-speed motility sometimes avoid grazing better than their nonmotile or slower strains [5] [11] especially the smallest, fastest bacteria. Moreover, a cell's movement strategy may be altered by predation. The bacteria move by run-and-reverse strategy, which help them to beat a hasty retreat before being trapped instead of moving by the run-and-tumble strategy. [17] However, there is a study showed that the probability of random contacts between predators and prey increases with bacterial swimming, and motile bacteria can be consumed at higher rates by HNFs. [18] In addition, bacterial surface properties affect predation as well as other factors. For example, there is an evidence shows that protists prefer gram-negative bacteria than gram-positive bacteria. Protists consume gram-positive cells at much lower rates than consuming gram-negative cells. The heterotrophic nanoflagellates actively avoid grazing on gram-positive actinobacteria as well. Grazing on gram-positive cells takes longer digestion time than on gram-negative cells. [11] [19] As a result of this, the predator cannot handle more prey until the previous ingested material is consumed or expelled. Moreover, bacterial cell surface charge and hydrophobicity have also been suggested that might reduce grazing ability. [20] Another strategy that bacteria can use for avoiding the predation is to poison their predator. For example, certain bacteria such as Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa can secrete toxin agents related to quorum sensing to kill their predators. [11]