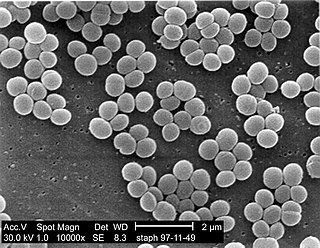

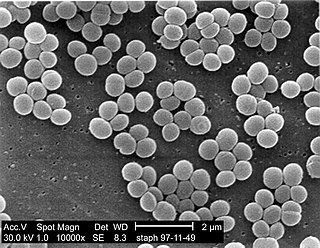

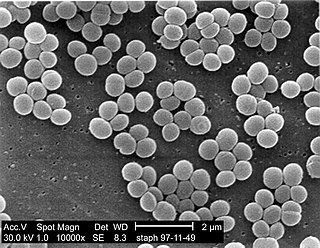

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often positive for catalase and nitrate reduction and is a facultative anaerobe that can grow without the need for oxygen. Although S. aureus usually acts as a commensal of the human microbiota, it can also become an opportunistic pathogen, being a common cause of skin infections including abscesses, respiratory infections such as sinusitis, and food poisoning. Pathogenic strains often promote infections by producing virulence factors such as potent protein toxins, and the expression of a cell-surface protein that binds and inactivates antibodies. S. aureus is one of the leading pathogens for deaths associated with antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains, such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), is a worldwide problem in clinical medicine. Despite much research and development, no vaccine for S. aureus has been approved.

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a group of gram-positive bacteria that are genetically distinct from other strains of Staphylococcus aureus. MRSA is responsible for several difficult-to-treat infections in humans. It caused more than 100,000 deaths worldwide attributable to antimicrobial resistance in 2019.

Acute septic arthritis, infectious arthritis, suppurative arthritis, pyogenic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or joint infection is the invasion of a joint by an infectious agent resulting in joint inflammation. Generally speaking, symptoms typically include redness, heat and pain in a single joint associated with a decreased ability to move the joint. Onset is usually rapid. Other symptoms may include fever, weakness and headache. Occasionally, more than one joint may be involved, especially in neonates, younger children and immunocompromised individuals. In neonates, infants during the first year of life, and toddlers, the signs and symptoms of septic arthritis can be deceptive and mimic other infectious and non-infectious disorders.

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the inner surface of the heart, usually the valves. Signs and symptoms may include fever, small areas of bleeding into the skin, heart murmur, feeling tired, and low red blood cell count. Complications may include backward blood flow in the heart, heart failure – the heart struggling to pump a sufficient amount of blood to meet the body's needs, abnormal electrical conduction in the heart, stroke, and kidney failure.

Cefazolin, also known as cefazoline and cephazolin, is a first-generation cephalosporin antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. Specifically it is used to treat cellulitis, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, endocarditis, joint infection, and biliary tract infections. It is also used to prevent group B streptococcal disease around the time of delivery and before surgery. It is typically given by injection into a muscle or vein.

A hospital-acquired infection, also known as a nosocomial infection, is an infection that is acquired in a hospital or other healthcare facility. To emphasize both hospital and nonhospital settings, it is sometimes instead called a healthcare-associated infection. Such an infection can be acquired in a hospital, nursing home, rehabilitation facility, outpatient clinic, diagnostic laboratory or other clinical settings. A number of dynamic processes can bring contamination into operating rooms and other areas within nosocomial settings. Infection is spread to the susceptible patient in the clinical setting by various means. Healthcare staff also spread infection, in addition to contaminated equipment, bed linens, or air droplets. The infection can originate from the outside environment, another infected patient, staff that may be infected, or in some cases, the source of the infection cannot be determined. In some cases the microorganism originates from the patient's own skin microbiota, becoming opportunistic after surgery or other procedures that compromise the protective skin barrier. Though the patient may have contracted the infection from their own skin, the infection is still considered nosocomial since it develops in the health care setting. Nosocomial infection tends to lack evidence that it was present when the patient entered the healthcare setting, thus meaning it was acquired post-admission.

Bacterial pneumonia is a type of pneumonia caused by bacterial infection.

A boil, also called a furuncle, is a deep folliculitis, which is an infection of the hair follicle. It is most commonly caused by infection by the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, resulting in a painful swollen area on the skin caused by an accumulation of pus and dead tissue. Boils are therefore basically pus-filled nodules. Individual boils clustered together are called carbuncles. Most human infections are caused by coagulase-positive S. aureus strains, notable for the bacteria's ability to produce coagulase, an enzyme that can clot blood. Almost any organ system can be infected by S. aureus.

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) are strains of Staphylococcus aureus that have acquired resistance to the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin. Bacteria can acquire resistant genes either by random mutation or through the transfer of DNA from one bacterium to another. Resistance genes interfere with the normal antibiotic function and allow a bacteria to grow in the presence of the antibiotic. Resistance in VRSA is conferred by the plasmid-mediated vanA gene and operon. Although VRSA infections are uncommon, VRSA is often resistant to other types of antibiotics and a potential threat to public health because treatment options are limited. VRSA is resistant to many of the standard drugs used to treat S. aureus infections. Furthermore, resistance can be transferred from one bacterium to another.

A blood culture is a medical laboratory test used to detect bacteria or fungi in a person's blood. Under normal conditions, the blood does not contain microorganisms: their presence can indicate a bloodstream infection such as bacteremia or fungemia, which in severe cases may result in sepsis. By culturing the blood, microbes can be identified and tested for resistance to antimicrobial drugs, which allows clinicians to provide an effective treatment.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia contracted by a person outside of the healthcare system. In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is seen in patients who have recently visited a hospital or who live in long-term care facilities. CAP is common, affecting people of all ages, and its symptoms occur as a result of oxygen-absorbing areas of the lung (alveoli) filling with fluid. This inhibits lung function, causing dyspnea, fever, chest pains and cough.

Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a fastidious, slow-growing, Gram-negative rod of the genus Capnocytophaga. It is a commensal bacterium in the normal gingival flora of canine and feline species, but can cause illness in humans. Transmission may occur through bites, licks, or even close proximity with animals. C. canimorsus generally has low virulence in healthy individuals, but has been observed to cause severe, even grave, illness in persons with pre-existing conditions. The pathogenesis of C. canimorsus is still largely unknown, but increased clinical diagnoses have fostered an interest in the bacillus. Treatment with antibiotics is effective in most cases, but the most important yet basic diagnostic tool available to clinicians remains the knowledge of recent exposure to canines or felines.

Pseudomonas oryzihabitans is a nonfermenting yellow-pigmented, gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that can cause sepsis, peritonitis, endophthalmitis, and bacteremia. It is an opportunistic pathogen of humans and warm-blooded animals that is commonly found in several environmental sources, from soil to rice paddies. They can be distinguished from other nonfermenters by their negative oxidase reaction and aerobic character. This organism can infect individuals that have major illnesses, including those undergoing surgery or with catheters in their body. Based on the 16S RNA analysis, these bacteria have been placed in the Pseudomonas putida group.

Ceftobiprole, sold under the brand name Zevtera among others, is a fifth-generation cephalosporin antibacterial used for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia and community-acquired pneumonia. It is marketed by Basilea Pharmaceutica under the brand names Zevtera and Mabelio. Like other cephalosporins, ceftobiprole exerts its antibacterial activity by binding to important penicillin-binding proteins and inhibiting their transpeptidase activity which is essential for the synthesis of bacterial cell walls. Ceftobiprole has high affinity for penicillin-binding protein 2a of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains and retains its activity against strains that express divergent mecA gene homologues. Ceftobiprole also binds to penicillin-binding protein 2b in Streptococcus pneumoniae (penicillin-intermediate), to penicillin-binding protein 2x in Streptococcus pneumoniae (penicillin-resistant), and to penicillin-binding protein 5 in Enterococcus faecalis.

A staphylococcal infection or staph infection is an infection caused by members of the Staphylococcus genus of bacteria.

Staphylococcus capitis is a coagulase-negative species (CoNS) of Staphylococcus. It is part of the normal flora of the skin of the human scalp, face, neck, scrotum, and ears and has been associated with prosthetic valve endocarditis, but is rarely associated with native valve infection.

Staphylococcus is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria in the family Staphylococcaceae from the order Bacillales. Under the microscope, they appear spherical (cocci), and form in grape-like clusters. Staphylococcus species are facultative anaerobic organisms.

ESKAPE is an acronym comprising the scientific names of six highly virulent and antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens including: Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp. The acronym is sometimes extended to ESKAPEE to include Escherichia coli. This group of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria can evade or 'escape' commonly used antibiotics due to their increasing multi-drug resistance (MDR). As a result, throughout the world, they are the major cause of life-threatening nosocomial or hospital-acquired infections in immunocompromised and critically ill patients who are most at risk. P. aeruginosa and S. aureus are some of the most ubiquitous pathogens in biofilms found in healthcare. P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium, commonly found in the gut flora, soil, and water that can be spread directly or indirectly to patients in healthcare settings. The pathogen can also be spread in other locations through contamination, including surfaces, equipment, and hands. The opportunistic pathogen can cause hospitalized patients to have infections in the lungs, blood, urinary tract, and in other body regions after surgery. S. aureus is a Gram-positive, cocci-shaped bacterium, residing in the environment and on the skin and nose of many healthy individuals. The bacterium can cause skin and bone infections, pneumonia, and other types of potentially serious infections if it enters the body. S. aureus has also gained resistance to many antibiotic treatments, making healing difficult. Because of natural and unnatural selective pressures and factors, antibiotic resistance in bacteria usually emerges through genetic mutation or acquires antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs) through horizontal gene transfer - a genetic exchange process by which antibiotic resistance can spread.

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI), also known as peri-prosthetic joint infection (PJI), is an acute, sub-acute or chronic infection of a prosthetic joint. It may occur in the period after the joint replacement or many years later. It usually presents as joint pain, erythema, joint swelling and sometimes formation of a sinus tract. PJI is estimated to occur in approximately 2% of hip and knee replacements, and up to 4% of revision hip or knee replacements. Other estimates indicate that 1.4-2.5% of all joint replacements worldwide are complicated by PJIs. The incidence is expected to rise significantly in the future as hip replacements and knee replacements become more common. It is usually caused by aerobic gram positive bacteria, such as Staph epidermidis or Staphylococcus aureus but enterococcus species, gram negative organisms and Cutibacterium are also known causes with fungal infections being a rare culprit. The definitive diagnosis is isolation of the causative organism from the synovial fluid, but signs of inflammation in the joint fluid and imaging may also aid in the diagnosis. The treatment is a combination of systemic antibiotics, debridement of infectious and necrotic tissue and local antibiotics applied to the joint space. The bacteria that usually cause prosthetic joint infections commonly form a biofilm, or a thick slime that is adherent to the artificial joint surface, thus making treatment challenging.