Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period 467.3 million years ago. The group is likely to have appeared first either during the Early Ordovician or Late Cambrian period. With approximately 250 species, the Eurypterida is the most diverse Paleozoic chelicerate order. Following their appearance during the Ordovician, eurypterids became major components of marine faunas during the Silurian, from which the majority of eurypterid species have been described. The Silurian genus Eurypterus accounts for more than 90% of all known eurypterid specimens. Though the group continued to diversify during the subsequent Devonian period, the eurypterids were heavily affected by the Late Devonian extinction event. They declined in numbers and diversity until becoming extinct during the Permian–Triassic extinction event 251.9 million years ago.

Hibbertopterus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Hibbertopterus have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Devonian period in Belgium, Scotland and the United States to the Carboniferous period in Scotland, Ireland, the Czech Republic and South Africa. The type species, H. scouleri, was first named as a species of the significantly different Eurypterus by Samuel Hibbert in 1836. The generic name Hibbertopterus, coined more than a century later, combines his name and the Greek word πτερόν (pteron) meaning "wing".

Carcinosoma is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Carcinosoma are restricted to deposits of late Silurian age. Classified as part of the family Carcinosomatidae, which the genus lends its name to, Carcinosoma contains seven species from North America and Great Britain.

Chasmataspidids, sometime referred to as chasmataspids, are a group of extinct chelicerate arthropods that form the order Chasmataspidida. Chasmataspidids are probably related to horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura) and/or sea scorpions (Eurypterida), with more recent studies suggest that they form a clade (Dekatriata) with Eurypterida and Arachnida. Chasmataspidids are known sporadically in the fossil record through to the mid-Devonian, with possible evidence suggesting that they were also present during the late Cambrian. Chasmataspidids are most easily recognised by having an opisthosoma divided into a wide forepart (preabdomen) and a narrow hind part (postabdomen) each comprising 4 and 9 segments respectively. There is some debate about whether they form a natural group.

Nanahughmilleria is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Nanahughmilleria have been discovered in deposits of Devonian and Silurian age in the United States, Norway, Russia, England and Scotland, and have been referred to several different species.

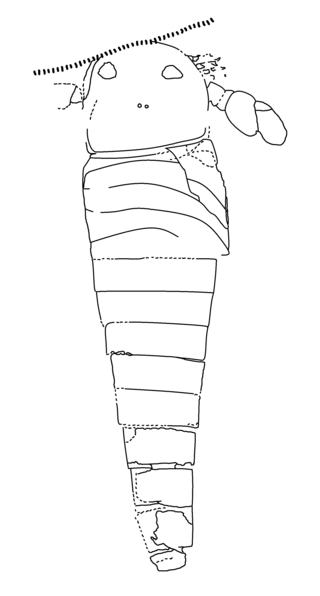

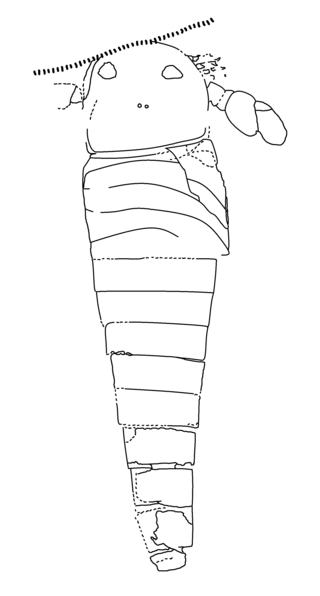

Onychopterella is a genus of predatory eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Onychopterella have been discovered in deposits from the Late Ordovician to the Late Silurian. The genus contains three species: O. kokomoensis, the type species, from the Early Pridoli epoch of Indiana; O. pumilus, from the Early Llandovery epoch of Illinois, both from the United States; and O. augusti, from the Late Hirnantian to Early Rhuddanian stages of South Africa.

Willwerathia is a genus of Devonian arthropod. It is sometimes classified as synziphosurine, a paraphyletic group of horseshoe crab-like fossil chelicerate arthropods, while some studies compare its morphology to an artiopod. Willwerathia known only by one species, Willwerathia laticeps, discovered in deposits of the Devonian period from the Klerf Formation, in the Rhenish Slate Mountains of Germany.

Tylopterella is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Only one fossil of the single and type species, T. boylei, has been discovered in deposits of the Late Silurian period in Elora, Canada. The name of the genus is composed by the Ancient Greek words τύλη, meaning "knot", and πτερόν, meaning "wing". The species name boylei honors David Boyle, who discovered the specimen of Tylopterella.

Parahughmilleria is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Parahughmilleria have been discovered in deposits of the Devonian and Silurian age in the United States, Canada, Russia, Germany, Luxembourg and Great Britain, and have been referred to several different species. The first fossils of Parahughmilleria, discovered in the Shawangunk Mountains in 1907, were initially assigned to Eurypterus. It would not be until 54 years later when Parahughmilleria would be described.

Legrandella is a genus of synziphosurine, a paraphyletic group of fossil chelicerate arthropods. Legrandella was regarded as part of the clade Prosomapoda. Fossils of the single and type species, L. lombardii, have been discovered in deposits of the Devonian period in Cochabamba, Bolivia.

Pasternakevia is a genus of synziphosurine, a paraphyletic group of fossil chelicerate arthropods. Pasternakevia was regarded as part of the clade Planaterga. Fossils of the single and type species, P. podolica, have been discovered in deposits of the Silurian period in Podolia, Ukraine.

Weinbergina is a genus of synziphosurine, a paraphyletic group of fossil chelicerate arthropods. Fossils of the single and type species, W. opitzi, have been discovered in deposits of the Devonian period in the Hunsrück Slate, Germany.

Synziphosurina is a paraphyletic group of chelicerate arthropods previously thought to be basal horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura). It was later identified as a grade composed of various basal euchelicerates, eventually excluded from the monophyletic Xiphosura sensu stricto and only regarded as horseshoe crabs under a broader sense. Synziphosurines survived at least since early Ordovician to early Carboniferous in ages, with most species are known from the in-between Silurian strata.

Pterygotidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. They were members of the superfamily Pterygotioidea. Pterygotids were the largest known arthropods to have ever lived with some members of the family, such as Jaekelopterus and Acutiramus, exceeding 2 metres (6.6 ft) in length. Their fossilized remains have been recovered in deposits ranging in age from 428 to 372 million years old.

Pterygotioidea is a superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Pterygotioids were the most derived members of the infraorder Diploperculata and the sister group of the adelophthalmoid eurypterids. The group includes the basal and small hughmilleriids, the larger and specialized slimonids and the famous pterygotids which were equipped with robust and powerful cheliceral claws.

Slimonidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Slimonids were members of the superfamily Pterygotioidea and the family most closely related to the derived pterygotid eurypterids, which are famous for their cheliceral claws and great size. Many characteristics of the Slimonidae, such as their flattened and expanded telsons, support a close relationship between the two groups.

The metastoma is a ventral single plate located in the opisthosoma of non-arachnid dekatriatan chelicerates such as eurypterids, chasmataspidids and the genus Houia. The metastoma located between the base of 6th prosomal appendage pair and may had functioned as part of the animal's feeding structures. It most likely represented a fused appendage pair originated from somite 7, thus homologous to the chilaria of horseshoe crab and 4th walking leg pair of sea spider. In eurypterids, the plate was typically cordate (heart-shaped) in shape, though differed in shape in some genera, such as Megalograptus.

Dvulikiaspis is a genus of chasmataspidid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of the single and type species, D. menneri, have been discovered in deposits of the Early Devonian period in the Krasnoyarsk Krai, Siberia, Russia. The name of the genus is composed by the Russian word двуликий (dvulikij), meaning "two-faced", and the Ancient Greek word ἀσπίς (aspis), meaning "shield". The species name honors the discoverer of the holotype of Dvulikiaspis, Vladimir Vasilyevich Menner.

Camanchia is a genus of synziphosurine, a paraphyletic group of fossil chelicerate arthropods. Camanchia was regarded as part of the clade Prosomapoda. Fossils of the single and type species, C. grovensis, have been discovered in deposits of the Silurian period in Iowa, in the United States. Alongside Venustulus, Camanchia is one of the only Silurian synziphosurine with fossil showing evidence of appendages.

Anderella is a genus of synziphosurine, a paraphyletic group of fossil chelicerate arthropods. Anderella was regarded as part of the clade Prosomapoda. Fossils of the single and type species, A. parva, have been discovered in deposits of the Carboniferous period in Montana, in the United States. Anderella is the first and so far the only Carboniferous synziphosurine being described, making it the youngest member of synziphosurines. Anderella is also one of the few synziphosurine genera with fossil showing evidence of appendages, but the details are obscure due to their poor preservation.