| Catechism of a Revolutionary | |

|---|---|

| Created | 1869 |

| Author(s) | Sergey Nechayev |

The Catechism of a Revolutionary is a manifesto written by Russian revolutionary Sergey Nechayev between April and August 1869.

| Catechism of a Revolutionary | |

|---|---|

| Created | 1869 |

| Author(s) | Sergey Nechayev |

The Catechism of a Revolutionary is a manifesto written by Russian revolutionary Sergey Nechayev between April and August 1869.

The manifesto is a manual for the formation of secret societies.

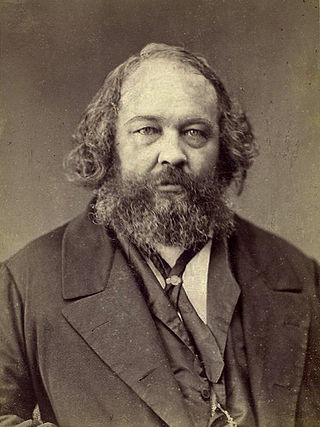

It is debated how much input Mikhail Bakunin had or if it is solely the work of Nechayev. [1] The work called for total devotion to a revolutionary lifestyle. [2] Its publication in the Government Herald in July 1871 as the manifesto of the Narodnaya Rasprava secret society ("Общество народной расправы") was one of the most dramatic events of Nechayev's revolutionary life, [3] [4] [5] through its words and the actions it inspired establishing Nechayev's importance for the Nihilist movement. [6]

The Catechism is divided into two sections; General Rules of the Organisation and Rules of Conduct of Revolutionaries, 22 and 26 paragraphs long respectively; [4] abridged versions were published as excerpts in the anarchist periodicals Freiheit and The Alarm . [7]

The most radical document of its age, [8] the Catechism outlined the authors' revolutionary Jacobin program of organisation and discipline, a program that became the backbone of the radical movement in Russia. The revolutionary is portrayed in the Catechism as an amoral avenging angel, an expendable resource in the service of the revolution, [6] committed to any crime or treachery necessary to effect the downfall of the prevailing order. [4]

The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it.

— Catechism of a Revolutionary, opening lines [7]

Critics of anarcho-communism argue that the Catechism reflects the innately violent and nihilistic nature of the philosophy. [9] Scholar Michael Allen Gillespie has hailed the Catechism as "a pre-eminent expression of the doctrine of freedom and negation" that arose in the Fichtean notion of the "Absolute I" that had been concealed in Left Hegelianism. [6] Prominent Black Panther of the 20th century Eldridge Cleaver adopted the Catechism as a "revolutionary bible", incorporating it into his daily life to the extent that he employed, in his words, "tactics of ruthlessness in my dealings with everyone with whom I came into contact". [10] The ideas and sentiments in the work had been in part previously aired by Pyotr Zaichnevsky and Nikolai Ishutin in Russia, and by Carbonari and Young Italy in the West. [11]

The journal Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique published a letter from Bakunin to Nechayev, in which Bakunin wrote, "You remember how you were angry with me, when I called you abrek and called your Catechism the Catechism of abreks?" [12]

The Catechism of a Revolutionary, a chilling blueprint for the ideal "New Man," was the manifesto of a secret society called The People's Revenge (Narodnaya Rasprava)...

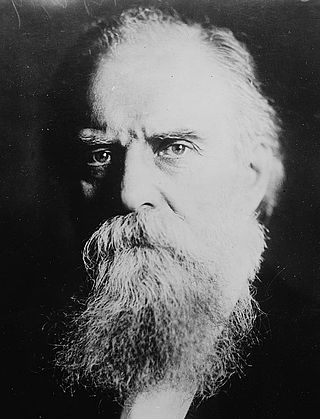

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, social anarchist, and collectivist anarchist traditions. Bakunin's prestige as a revolutionary also made him one of the most famous ideologues in Europe, gaining substantial influence among radicals throughout Russia and Europe.

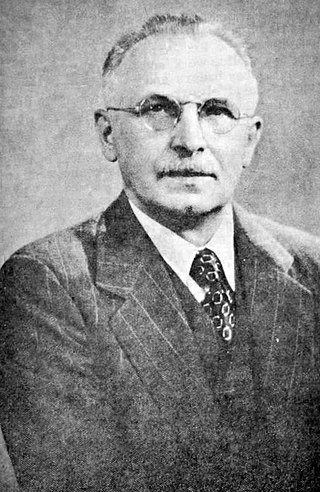

Grigorii Petrovich Maksimov was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist. From the first days of the Russian Revolution, he played a leading role in the country's syndicalist movement – editing the newspaper Golos Truda and organising the formation of factory committees. Following the October Revolution, he came into conflict with the Bolsheviks, who he fiercely criticised for their authoritarian and centralist tendencies. For his anti-Bolshevik activities, he was eventually arrested and imprisoned, before finally being deported from the country. In exile, he continued to lead the anarcho-syndicalist movement, spearheading the establishment of the International Workers' Association (IWA), of which he was a member until his death.

Sergey Gennadiyevich Nechayev was a Russian anarcho-communist, part of the Russian nihilist movement, known for his single-minded pursuit of revolution by any means necessary, including revolutionary terror.

According to different scholars, the history of anarchism either goes back to ancient and prehistoric ideologies and social structures, or begins in the 19th century as a formal movement. As scholars and anarchist philosophers have held a range of views on what anarchism means, it is difficult to outline its history unambiguously. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined movement stemming from 19th-century class conflict, while others identify anarchist traits long before the earliest civilisations existed.

The Russian nihilist movement was a philosophical, cultural, and revolutionary movement in the Russian Empire during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, from which the broader philosophy of nihilism originated. In Russian, the word nigilizm came to represent the movement's unremitting attacks on morality, religion, and traditional society. Even as it was yet unnamed, the movement arose from a generation of young radicals disillusioned with the social reformers of the past, and from a growing divide between the old aristocratic intellectuals and the new radical intelligentsia.

The Circle of Tchaikovsky, also known as Tchaikovtsy/Chaikovtsy, or the Grand Propaganda Society was a Russian literary society for self-education and a revolutionary organization of the Narodniks in the early 1870s. It was named after Nikolai Tchaikovsky, one of its prominent members.

Varlam Nikolozi dze Cherkezishvili was a Georgian aristocrat and journalist involved in Georgian anarchist and national liberation movements.

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who inhabited the region up until the 18th century. Philosophical anarchism first emerged from the radical movement during the Ukrainian national revival, finding a literary expression in the works of Mykhailo Drahomanov, who was himself inspired by the libertarian socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. The spread of populist ideas by the Narodniks also lay the groundwork for the adoption of anarchism by Ukraine's working classes, gaining notable circulation in the Jewish communities of the Pale of Settlement.

Anarchism in Russia developed out of the populist and nihilist movements' dissatisfaction with the government reforms of the time.

The Manifesto of the Sixteen, or Proclamation of the Sixteen, was a document drafted in 1916 by eminent anarchists Peter Kropotkin and Jean Grave which advocated an Allied victory over Germany and the Central Powers during the First World War. At the outbreak of the war, Kropotkin and other anarchist supporters of the Allied cause advocated their position in the pages of the Freedom newspaper, provoking sharply critical responses. As the war continued, anarchists across Europe campaigned in anti-war movements and wrote denunciations of the war in pamphlets and statements, including one February 1916 statement signed by prominent anarchists such as Emma Goldman and Rudolf Rocker.

Alexander "Sanya" Moiseyevich Schapiro or Shapiro was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist activist. Born in southern Russia, Schapiro left Russia at an early age and spent most of his early activist years in London.

Golos Truda was a Russian-language anarchist newspaper. Founded by working-class Russian expatriates in New York City in 1911, Golos Truda shifted to Petrograd during the Russian Revolution in 1917, when its editors took advantage of the general amnesty and right of return for political dissidents. There, the paper integrated itself into the anarchist labour movement, pronounced the necessity of a social revolution of and by the workers, and situated itself in opposition to the myriad of other left-wing movements.

Marie Le Compte was an American journal editor and anarchist who was active during the early 1880s.

Burevestnik was a newspaper published daily from Petrograd, Russia. Burevestnik was the organ of the Petrograd Federation of Anarchist Groups. The newspaper was founded in November 1917. Burevestnik was primarily distributed in Vyborg district, Kronstadt, Kolpino and Obukhovo. It had a readership of around 25,000. This newspaper was one of several publications with the name Burevestnik, a name originating in Maxim Gorky's poem Song of the Stormy Petrel.

Platformism is an anarchist organizational theory that aims to create a tightly-coordinated anarchist federation. Its main features include a common tactical line, a unified political policy and a commitment to collective responsibility.

Maria Isidorovna Goldsmith, also known as Marie Goldsmith, was a Russian Jewish anarchist and collaborator of Peter Kropotkin. She also wrote under the pseudonyms Maria Isidine and Maria Korn.

Anatoli Grigorievich Zhelezniakov (1895–1919) was a Russian anarchist and revolutionary best known for dispersing the short-lived Russian Constituent Assembly on Bolshevik orders during the October Revolution.

The Chicago idea is an ideology combining anarchism and revolutionary unionism. It was a precursor to anarcho-syndicalism professed by Chicago anarchists, especially Albert Parsons and August Spies, in the mid-1880s.

Anarchism in Georgia began to emerge during the late 19th century out of the Georgian national liberation movement and the Russian nihilist movement. It reached its apex during the 1905 Russian Revolution, after a number of anarchists returned from exile to participate in revolutionary activities, such as in the newly-established Gurian Republic.

Yakov Isaevich Kirilovskii, commonly known by his pseudonym Daniil Novomirskii, was a Ukrainian Jewish anarcho-syndicalist. A leading figure in the Ukrainian syndicalist movement, Novomirskii sharply criticised the terrorist tactics of anarchist communism and the opportunism of social democracy. His South Russian Group of Anarcho-Syndicalists grew in popularity among workers throughout Ukraine, but it was suppressed in the aftermath of the 1905 Revolution and Novomirskii himself was imprisoned. After the 1917 Revolution, he became a notable anarchist supporter of the Russian Communist Party, although he was later disillusioned by its implementation of the New Economic Policy. He and his wife disappeared into the Gulag during the Great Purge.