Overview of and topical guide to anarchism

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to anarchism:

Contents

- Nature

- Schools of thought

- Classical

- Post-classical

- Contemporary

- Organizational forms

- History

- Timeline of major events

- History by region

- Historians

- Organizations

- Notable organizations

- Structures

- Literature

- Manifestos and expositions

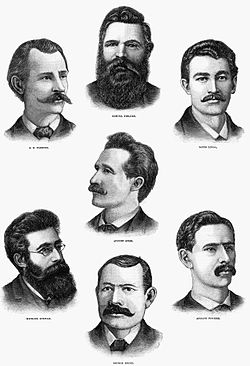

- Notable figures

- Non-anarchists influential on anarchism

- Places named after anarchists

- Related philosophies

- See also

- Footnotes

- Further reading

- External links