Dendrobranchiata is a suborder of decapods, commonly known as prawns. There are 540 extant species in seven families, and a fossil record extending back to the Devonian. They differ from related animals, such as Caridea and Stenopodidea, by the branching form of the gills and by the fact that they do not brood their eggs, but release them directly into the water. They may reach a length of over 330 millimetres (13 in) and a mass of 450 grams (1.0 lb), and are widely fished and farmed for human consumption.

Derocheilocarididae is a family of marine crustaceans that form part of the meiobenthos. It is the only family in the monotypic order Mystacocaridida, and the monotypic subclass Mystacocarida. These mystacocarids are less than 1 mm (0.04 in) long, and live interstitially in the intertidal zones of sandy beaches.

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six classes of pancrustaceans behind insects, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill, prawns, woodlice, amphipods, mantis shrimp, tongue-eating lice and many other less familiar animals. They are abundant in all marine environments and have colonised freshwater and terrestrial habitats. They are segmented animals, united by a common body plan comprising 20 body segments, and divided into a head, thorax, and abdomen.

Mysida is an order of small, shrimp-like crustaceans in the malacostracan superorder Peracarida. Their common name opossum shrimps stems from the presence of a brood pouch or "marsupium" in females. The fact that the larvae are reared in this pouch and are not free-swimming characterises the order. The mysid's head bears a pair of stalked eyes and two pairs of antennae. The thorax consists of eight segments each bearing branching limbs, the whole concealed beneath a protective carapace and the abdomen has six segments and usually further small limbs.

Isopoda is an order of crustaceans. Members of this group are called isopods and include both aquatic species, and terrestrial species such as woodlice. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons, two pairs of antennae, seven pairs of jointed limbs on the thorax, and five pairs of branching appendages on the abdomen that are used in respiration. Females brood their young in a pouch under their thorax.

Clam shrimp are a group of bivalved branchiopod crustaceans that resemble the unrelated bivalved molluscs. They are extant and also known from the fossil record, from at least the Devonian period and perhaps before. They were originally classified in the former order Conchostraca, which later proved to be paraphyletic, because water fleas are nested within clam shrimps. Clam shrimp are now divided into three orders, Cyclestherida, Laevicaudata, and Spinicaudata, in addition to the fossil family Leaiidae.

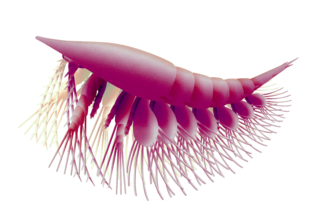

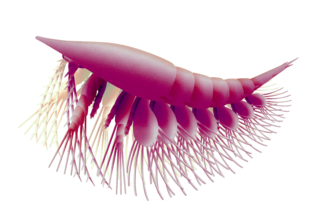

Anostraca is one of the four orders of crustaceans in the class Branchiopoda; its members are referred to as fairy shrimp. They live in vernal pools and hypersaline lakes across the world, and they have even been found in deserts, ice-covered mountain lakes, and Antarctic ice. They are usually 6–25 mm (0.24–0.98 in) long. Most species have 20 body segments, bearing 11 pairs of leaf-like phyllopodia, and the body lacks a carapace. They swim "upside-down" and feed by filtering organic particles from the water or by scraping algae from surfaces, with the exception of Branchinecta gigas, or "giant fairy shrimp", which is itself a predator of other species of anostracans. They are an important food for many birds and fish, and some are cultured and harvested for use as fish food. There are 300 species spread across 8 families.

The crustacean order Tanaidacea make up a minor group within the class Malacostraca. There are about 940 species in this order.

Leptostraca is an order of small, marine crustaceans. Its members, including the well-studied Nebalia, occur throughout the world's oceans and are usually considered to be filter-feeders. It is the only extant order in the subclass Phyllocarida. They are believed to represent the most primitive members of their class, the Malacostraca, and first appear in the fossil record during the Cambrian period.

The family Argulidae, whose members are commonly known as carp lice or fish lice, are parasitic crustaceans in the class Ichthyostraca. It is the only family in the monotypic subclass Branchiura and the order Arguloida, although a second family, Dipteropeltidae, has been proposed. Although they are thought to be primitive forms, they have no fossil record.

Amphionides reynaudii is a species of caridean shrimp, whose identity and position in the crustacean system remained enigmatic for a long time. It is a small planktonic crustacean found throughout the world's tropical oceans, which until 2015 was considered the sole representative of the order Amphionidacea, due to unusual morphological features. Molecular data however confirm it as a member of the caridean family Pandalidae, and the confusion of morphology is because only larval phases have so far been studied.

Eumalacostraca is a subclass of crustaceans, containing almost all living malacostracans, or about 40,000 described species. The remaining subclasses are the Phyllocarida and possibly the Hoplocarida. Eumalacostracans have 19 segments. This arrangement is known as the "caridoid facies", a term coined by William Thomas Calman in 1909. The thoracic limbs are jointed and used for swimming or walking. The common ancestor is thought to have had a carapace, and most living species possess one, but it has been lost in some subgroups.

Triops longicaudatus is a freshwater crustacean of the order Notostraca, resembling a miniature horseshoe crab. It is characterized by an elongated, segmented body, a flattened shield-like brownish carapace covering two thirds of the thorax, and two long filaments on the abdomen. The genus name Triops comes from Greek ὤψ or ṓps, meaning "eye" prefixed with Latin tri-, "three", in reference to its three eyes. Longicaudatus is a Latin neologism combining longus ("long") and caudatus ("tailed"), referring to its long tail structures. Triops longicaudatus is found in fresh water ponds and pools, often in places where few higher forms of life can exist.

The (pan)arthropod head problem is a long-standing zoological dispute concerning the segmental composition of the heads of the various arthropod groups, and how they are evolutionarily related to each other. While the dispute has historically centered on the exact make-up of the insect head, it has been widened to include other living arthropods, such as chelicerates, myriapods, and crustaceans, as well as fossil forms, such as the many arthropods known from exceptionally preserved Cambrian faunas. While the topic has classically been based on insect embryology, in recent years a great deal of developmental molecular data has become available. Dozens of more or less distinct solutions to the problem, dating back to at least 1897, have been published, including several in the 2000s.

Eucrenonaspides oinotheke is a species of crustacean in the family Psammaspididae, endemic to Tasmania, the only species described in the genus Eucrenonaspides. Eucrenonaspides is in the order Anaspidacea. It was described from a spring at 9 Payton Place, Devonport, Tasmania in 1980, making it "the first spring-dwelling syncarid recorded from the Australian region". It is listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List. A further undescribed species is known from south-western Tasmania.

Crustaceans may pass through a number of larval and immature stages between hatching from their eggs and reaching their adult form. Each of the stages is separated by a moult, in which the hard exoskeleton is shed to allow the animal to grow. The larvae of crustaceans often bear little resemblance to the adult, and there are still cases where it is not known what larvae will grow into what adults. This is especially true of crustaceans which live as benthic adults, more-so than where the larvae are planktonic, and thereby easily caught.

Hutchinsoniella macracantha is a species of crustacean known as a horseshoe shrimp. It is the only species in the genus Hutchinsoniella and was first described in 1955 by Howard L. Sanders, having been discovered in Long Island Sound; they were the first example of a new class of crustacean that was given the name Cephalocarida.

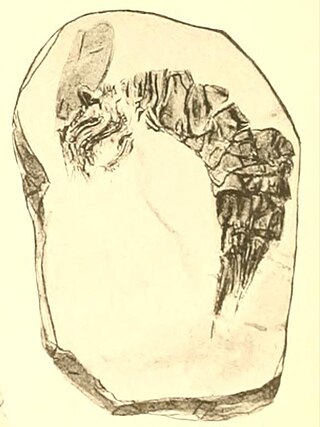

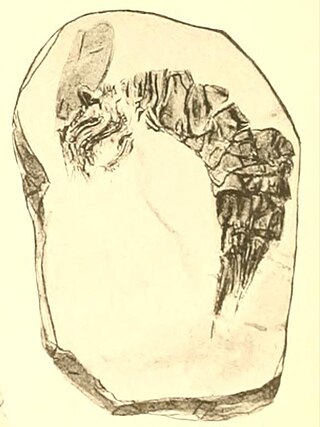

Schramidontus is a genus of crustaceans from the Late Devonian period found in Strud, Belgium, closely related to Angustidontus and classified as part of the order Angustidontida. It is an important genus because of its position in the eumalacostracan family tree and the insight study of the genus may give of the origin of the Decapoda. The generic name derives from Frederick Schram, who helped the scientific community in the field of the Palaeozoic malacostracans and the suffix -idontus in relation to the similarities between Schramidontus and Angustidontus. The specific name is from Labas, a stream that flows near Strud quarry, where the genus was discovered.

Oelandocaris is an extinct genus of stem-mandibulate, or possibly a megacheiran, within the monotypic family Oelandocarididae.

Bairdops is an extinct genus of mantis shrimp that lived during the Early Carboniferous period in what is now Scotland and the United States. Two named species are currently assigned to it. The type species, B. elegans, has been collected from several Dinantian-aged localities in Scotland, and was first described in 1908 by British geologist Ben Peach as a species of Perimecturus. The generic name was coined decades later in 1979 by American paleontologist Frederick Schram, and honors William Baird. A later species, B. beargulchensis, was named in 1978 after the Serpukhovian-aged Bear Gulch Limestone of Montana where it was discovered. The two species were originally deemed close relatives based on their physical similarities, but several cladistic analyses published since 1998 have suggested the genus may be polyphyletic.