The divine countenance is the face of God. The concept has special significance in the Abrahamic religions.

The divine countenance is the face of God. The concept has special significance in the Abrahamic religions.

Islam considers God to be beyond ordinary vision as the Quran states that "Sights cannot attain him; he can attain sights", [1] but other verses indicate that he would be visible in the hereafter. [2] The Quran makes many references to the face of God but its use of the Arabic word for a physical face —wajh— is symbolic and is used to refer to God's presence which, in Islam, is everywhere: "wherever you turn, there is the face of God". [3]

In Judaism and Christianity, the concept is the manifestation of God rather than a remote immanence or delegation of an angel, even though a mortal would not be able to gaze directly upon him. [4] In Jewish mysticism, it is traditionally believed that even the angels who attend him cannot endure seeing the divine countenance directly. [5] Where there are references to visionary encounters, these are thought to be either products of the human imagination, as in dreams or, alternatively, a sight of the divine glory which surrounds God, not the Godhead itself. [6]

An important early use of the concept in the Old Testament is the blessing passed by Moses to the children of Israel in the Book of Numbers. [7]

The LORD bless you and keep you:

The LORD make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you:

The LORD lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace. [8]

The name of the city of Peniel literally means the "face of God" in Hebrew. The place was named by Jacob after he wrestled an angel there, as recounted in the Book of Genesis. His opponent seemed divine and so Jacob claimed to have looked upon the face of God. [9]

Saint Paul in 1 Corinthians 13,11–12 states that the beatific vision of the face of God will be perfect solely in the afterlife.

In the Mandaean scripture of the Ginza Rabba (in Right Ginza books 1 and 2.1), the face or countenance of Hayyi Rabbi is referred to as the "Great Countenance of Glory" (Classical Mandaic : ࡐࡀࡓࡑࡅࡐࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ ࡖࡏࡒࡀࡓࡀ, romanized: parṣupa rba ḏ-ʿqara; Modern Mandaic pronunciation: [pɑrˈsˤufaˈrɑbbɑdˤiˈqɑra] ; also cognate with Classical Syriac : ܦܪܨܘܦܐ, romanized: prṣupa, lit. 'countenance', attested in the Peshitta including in Matthew 17:2 [10] ). [11] This Aramaic term is a borrowing from the Greek word prosopon . [12]

In pagan religions, the face of God might be viewed in a literal sense - the face of an idol in a temple. [13] In prayers and blessings, the concept was more metaphorical, indicating the favourable attention of the deity. For example, in the Babylonian blessing: [14]

God was represented by the Hand of God, in fact including the forearm but no more of the body, at several places in the 3rd-century Dura-Europos synagogue, presumably reflecting the usual practice in ancient Jewish art, almost all of which is now lost. The Hand convention was continued in Christian art, which also used full body depictions of the God the Son with the appearance of Jesus for Old Testament scenes, in particular the story of Adam and Eve, where God needed to be represented. [15] The biblical statements from Exodus and John quoted above were taken to apply not only to God the Father in person, but to all attempts at the depiction of his face. [16] The development of full images of God the Father in Western art was much later, and the aged white-haired appearance of the Ancient of Days gradually became the conventional representation, after a period of experimentation, especially in images the Trinity, where all three persons might be shown with the appearance of Jesus. In Eastern Orthodoxy the depiction of God the Father remains unusual, and has been forbidden at various church councils; many early Protestants did the same, and in the Counter Reformation the Catholic Church discouraged the earlier variety of depictions but explicitly supported the Ancient of Days.

The description of the Ancient of Days, identified with God by most commentators, [17] in the Book of Daniel is the nearest approach to a physical description of God in the Hebrew Bible: [18]

. ...the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire. (Daniel 7:9)

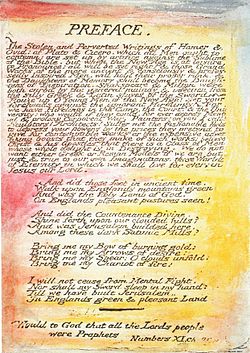

The "countenance divine" appears in the lines of the famous poem, And did those feet in ancient time , by William Blake which first appeared in the preface to his epic Milton: A Poem in Two Books . Blake thought highly of Milton's work saying, "I have the happiness of seeing the Divine countenance in ... Milton more distinctly than in any prince or hero." [19]

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)The ontological significance of the face of God is a theme that may be traced through every genre of the Hebrew Bible.

The panim (the face) of God