In geometry a quadrilateral is a four-sided polygon, having four edges (sides) and four corners (vertices). The word is derived from the Latin words quadri, a variant of four, and latus, meaning "side". It is also called a tetragon, derived from Greek "tetra" meaning "four" and "gon" meaning "corner" or "angle", in analogy to other polygons. Since "gon" means "angle", it is analogously called a quadrangle, or 4-angle. A quadrilateral with vertices , , and is sometimes denoted as .

In Euclidean plane geometry, a rectangle is a rectilinear convex polygon or a quadrilateral with four right angles. It can also be defined as: an equiangular quadrilateral, since equiangular means that all of its angles are equal ; or a parallelogram containing a right angle. A rectangle with four sides of equal length is a square. The term "oblong" is used to refer to a non-square rectangle. A rectangle with vertices ABCD would be denoted as ABCD.

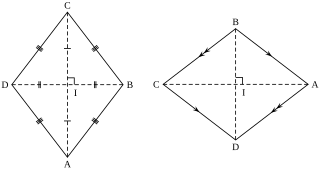

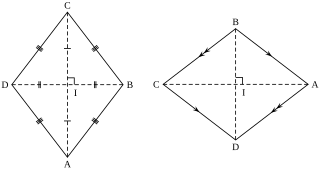

In Euclidean geometry, a kite is a quadrilateral with reflection symmetry across a diagonal. Because of this symmetry, a kite has two equal angles and two pairs of adjacent equal-length sides. Kites are also known as deltoids, but the word deltoid may also refer to a deltoid curve, an unrelated geometric object sometimes studied in connection with quadrilaterals. A kite may also be called a dart, particularly if it is not convex.

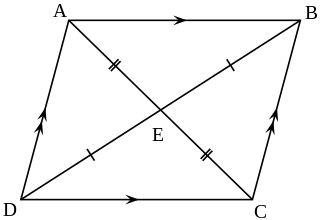

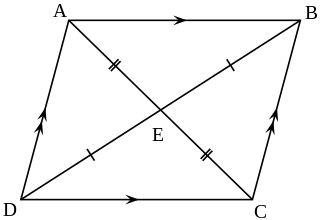

In Euclidean geometry, a parallelogram is a simple (non-self-intersecting) quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides. The opposite or facing sides of a parallelogram are of equal length and the opposite angles of a parallelogram are of equal measure. The congruence of opposite sides and opposite angles is a direct consequence of the Euclidean parallel postulate and neither condition can be proven without appealing to the Euclidean parallel postulate or one of its equivalent formulations.

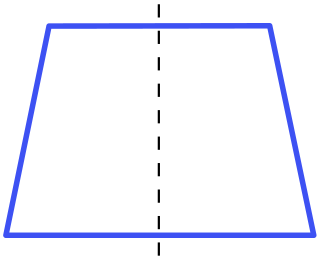

In geometry, bisection is the division of something into two equal or congruent parts. Usually it involves a bisecting line, also called a bisector. The most often considered types of bisectors are the segment bisector, a line that passes through the midpoint of a given segment, and the angle bisector, a line that passes through the apex of an angle . In three-dimensional space, bisection is usually done by a bisecting plane, also called the bisector.

In plane Euclidean geometry, a rhombus is a quadrilateral whose four sides all have the same length. Another name is equilateral quadrilateral, since equilateral means that all of its sides are equal in length. The rhombus is often called a "diamond", after the diamonds suit in playing cards which resembles the projection of an octahedral diamond, or a lozenge, though the former sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 60° angle, and the latter sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 45° angle.

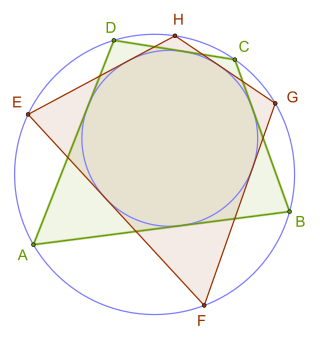

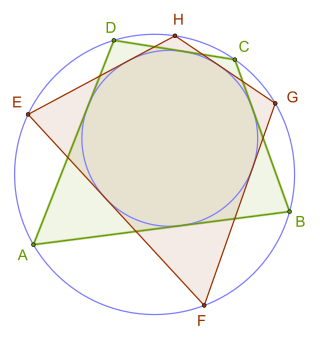

In Euclidean geometry, a cyclic quadrilateral or inscribed quadrilateral is a quadrilateral whose vertices all lie on a single circle. This circle is called the circumcircle or circumscribed circle, and the vertices are said to be concyclic. The center of the circle and its radius are called the circumcenter and the circumradius respectively. Other names for these quadrilaterals are concyclic quadrilateral and chordal quadrilateral, the latter since the sides of the quadrilateral are chords of the circumcircle. Usually the quadrilateral is assumed to be convex, but there are also crossed cyclic quadrilaterals. The formulas and properties given below are valid in the convex case.

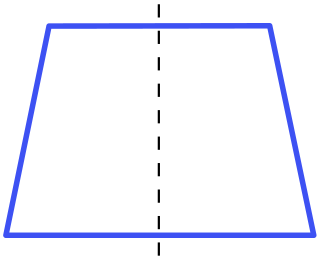

In geometry, a trapezoid in North American English, or trapezium in British English, is a quadrilateral that has one pair of parallel sides.

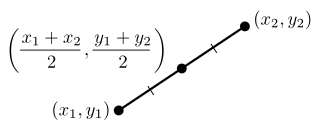

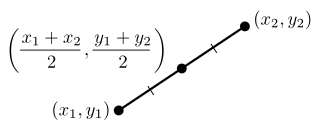

In geometry, the midpoint is the middle point of a line segment. It is equidistant from both endpoints, and it is the centroid both of the segment and of the endpoints. It bisects the segment.

In geometry, a set of points are said to be concyclic if they lie on a common circle. A polygon whose vertices are concyclic is called a cyclic polygon, and the circle is called its circumscribing circle or circumcircle. All concyclic points are equidistant from the center of the circle.

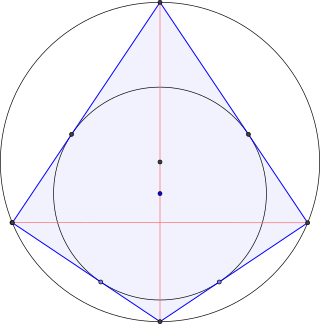

In Euclidean geometry, an isosceles trapezoid is a convex quadrilateral with a line of symmetry bisecting one pair of opposite sides. It is a special case of a trapezoid. Alternatively, it can be defined as a trapezoid in which both legs and both base angles are of equal measure, or as a trapezoid whose diagonals have equal length. Note that a non-rectangular parallelogram is not an isosceles trapezoid because of the second condition, or because it has no line of symmetry. In any isosceles trapezoid, two opposite sides are parallel, and the two other sides are of equal length, and the diagonals have equal length. The base angles of an isosceles trapezoid are equal in measure.

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four straight sides of equal length and four equal angles. It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length adjacent sides. It is the only regular polygon whose internal angle, central angle, and external angle are all equal (90°). A square with vertices ABCD would be denoted ABCD.

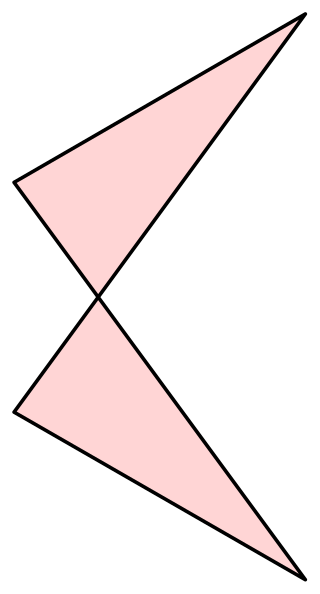

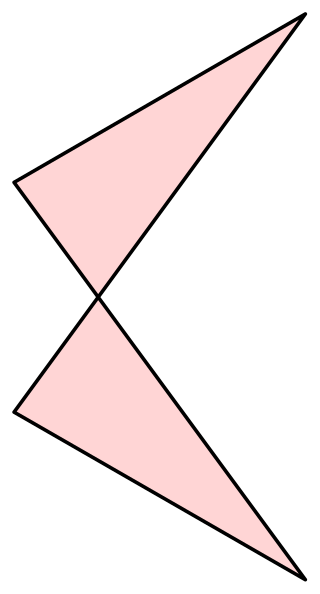

In geometry, an antiparallelogram is a type of self-crossing quadrilateral. Like a parallelogram, an antiparallelogram has two opposite pairs of equal-length sides, but these pairs of sides are not in general parallel. Instead, each pair of sides is antiparallel with respect to the other, with sides in the longer pair crossing each other as in a scissors mechanism. Whereas a parallelogram's opposite angles are equal and oriented the same way, an antiparallelogram's are equal but oppositely oriented. Antiparallelograms are also called contraparallelograms or crossed parallelograms.

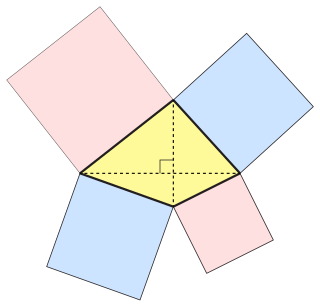

In Euclidean geometry, the British flag theorem says that if a point P is chosen inside a rectangle ABCD then the sum of the squares of the Euclidean distances from P to two opposite corners of the rectangle equals the sum to the other two opposite corners. As an equation:

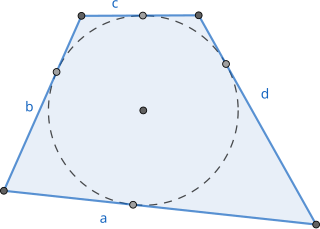

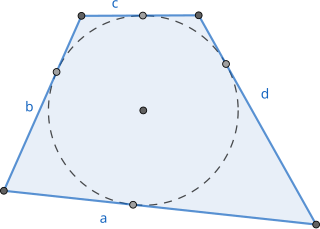

In Euclidean geometry, a tangential quadrilateral or circumscribed quadrilateral is a convex quadrilateral whose sides all can be tangent to a single circle within the quadrilateral. This circle is called the incircle of the quadrilateral or its inscribed circle, its center is the incenter and its radius is called the inradius. Since these quadrilaterals can be drawn surrounding or circumscribing their incircles, they have also been called circumscribable quadrilaterals, circumscribing quadrilaterals, and circumscriptible quadrilaterals. Tangential quadrilaterals are a special case of tangential polygons.

In Euclidean geometry, Varignon's theorem holds that the midpoints of the sides of an arbitrary quadrilateral form a parallelogram, called the Varignon parallelogram. It is named after Pierre Varignon, whose proof was published posthumously in 1731.

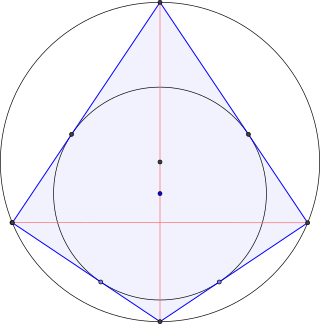

In Euclidean geometry, a bicentric quadrilateral is a convex quadrilateral that has both an incircle and a circumcircle. The radii and centers of these circles are called inradius and circumradius, and incenter and circumcenter respectively. From the definition it follows that bicentric quadrilaterals have all the properties of both tangential quadrilaterals and cyclic quadrilaterals. Other names for these quadrilaterals are chord-tangent quadrilateral and inscribed and circumscribed quadrilateral. It has also rarely been called a double circle quadrilateral and double scribed quadrilateral.

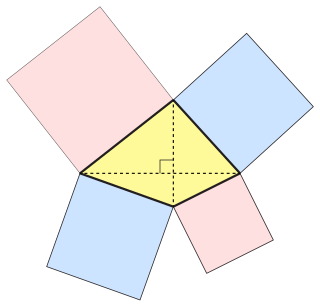

In Euclidean geometry, an orthodiagonal quadrilateral is a quadrilateral in which the diagonals cross at right angles. In other words, it is a four-sided figure in which the line segments between non-adjacent vertices are orthogonal (perpendicular) to each other.

In Euclidean geometry, a tangential trapezoid, also called a circumscribed trapezoid, is a trapezoid whose four sides are all tangent to a circle within the trapezoid: the incircle or inscribed circle. It is the special case of a tangential quadrilateral in which at least one pair of opposite sides are parallel. As for other trapezoids, the parallel sides are called the bases and the other two sides the legs. The legs can be equal, but they don't have to be.

In Euclidean geometry, a right kite is a kite that can be inscribed in a circle. That is, it is a kite with a circumcircle. Thus the right kite is a convex quadrilateral and has two opposite right angles. If there are exactly two right angles, each must be between sides of different lengths. All right kites are bicentric quadrilaterals, since all kites have an incircle. One of the diagonals divides the right kite into two right triangles and is also a diameter of the circumcircle.