Jacques Cartier was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, which he named "The Country of Canadas" after the Iroquoian names for the two big settlements he saw at Stadacona and at Hochelaga.

New France was the territory colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spain in 1763 under the Treaty of Paris.

Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve was a French military officer and the founder of Fort Ville-Marie in New France.

This section of the Timeline of Quebec history concerns the events between the foundation of Quebec and establishment of the Sovereign Council.

The 16th century in Canada saw the first contacts, since the Norsemen 500 years earlier, between the indigenous peoples in Canada living near the Atlantic coast and European fishermen, whalers, traders, and explorers.

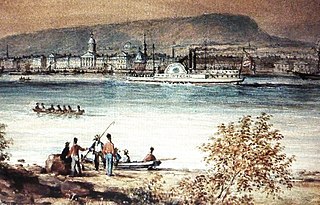

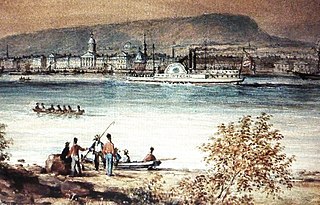

The history of the area around what is now known as Montreal, Montreal itself was established in 1642, located in what is now known as the province of Quebec, Canada, spans about 8,000 years. At the time of European contact, the area was inhabited by the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, a discrete and distinct group of Iroquoian-speaking indigenous people. They spoke Laurentian. Jacques Cartier became the first European to reach the area now known as Montreal in 1535 when he entered the village of Hochelaga on the Island of Montreal while in search of a passage to Asia during the Age of Exploration. Seventy years later, Samuel de Champlain unsuccessfully tried to create a fur trading post but the Mohawk of the Iroquois defended what they had been using as their hunting grounds.

Hochelaga-Maisonneuve is a neighbourhood in Montreal, Canada, situated in the east end of the island, generally to the south of the city's Olympic Stadium and east of downtown.

Kanesatake is a Mohawk settlement on the shore of the Lake of Two Mountains in southwestern Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Ottawa and Saint Lawrence rivers and about 48 kilometres (30 mi) west of Montreal. People who reside in Kanehsatà:ke are referred to as Mohawks of Kanesatake. As of 2022, the total registered population was 2,751, with a total of about 1,364 persons living on the territory. Both they and the Mohawk of Kahnawake, Quebec, a reserve located south of the river from Montreal, also control and have hunting and fishing rights to Doncaster 17 Indian Reserve.

Ville-Marie is the name of a borough (arrondissement) in the centre of Montreal, Quebec. The borough is named after Fort Ville-Marie, the French settlement that would later become Montreal, which was located within the present-day borough. Old Montreal is a National Historic Site of Canada.

Mercier–Hochelaga-Maisonneuve is a borough of Montreal, Quebec, Canada located in the southeastern end of the island.

Hochelaga was a St. Lawrence Iroquois 16th century fortified village on or near Mount Royal in present-day Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Jacques Cartier arrived by boat on October 2, 1535; he visited the village on the following day. He was greeted well by the Iroquois, and named the mountain he saw nearby Mount Royal. Several names in and around Montreal and the Hochelaga Archipelago can be traced back to him.

Old Montreal is a historic neighbourhood within the municipality of Montreal in the province of Quebec, Canada. Home to the Old Port of Montreal, the neighbourhood is bordered on the west by McGill Street, on the north by Ruelle des Fortifications, on the east by rue Saint-André, and on the south by the Saint Lawrence River. Following recent amendments, the neighbourhood has expanded to include the Rue des Soeurs Grises in the west, Saint Antoine Street in the north, and Saint Hubert Street in the east.

Pointe-à-Callière Museum is a museum of archaeology and history in Old Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It was founded in 1992 as part of celebrations to mark Montreal's 350th birthday. The museum has collections of artifacts from the First Nations of the Montreal region that illustrate how various cultures coexisted and interacted, and how the French and British regimes influenced the history of this territory over the years. The site of Pointe-à-Callière has been included in Montreal’s Birthplace National Historic Site since its designation in 1924.

Laurentian, or St. Lawrence Iroquoian, was an Iroquoian language spoken until the late 16th century along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River in present-day Quebec and Ontario, Canada. It is believed to have disappeared with the extinction of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, likely as a result of warfare by the more powerful Mohawk from the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy to the south, in present-day New York state of the United States.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians were an Iroquoian Indigenous people who existed from the 14th century to about 1580. They concentrated along the shores of the St. Lawrence River in present-day Quebec and Ontario, Canada, and in the American states of New York and northernmost Vermont. They spoke Laurentian languages, a branch of the Iroquoian family.

Odanak is an Abenaki First Nations reserve in the Central Quebec region, Quebec, Canada. The mostly First Nations population as of the Canada 2021 Census was 481. The territory is located near the mouth of the Saint-François River at its confluence with the St. Lawrence River. It is partly within the limits of Pierreville and across the river from Saint-François-du-Lac. Odanak is an Abenaki word meaning "in the village".

Events from the year 1611 in Quebec.

There are some hypotheses concerning the origin of the name of Montreal. The best-known is that it is a variant of "Mount Royal".

The timeline of Montreal history is a chronology of significant events in the history of Montreal, Canada's second-most populated city, with about 3.5 million residents in 2018, and the fourth-largest French-speaking city in the world.

The Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, otherwise known as the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle-France, was a religious organisation responsible for founding Ville-Marie, the original name for the settlement that would later become Montreal. The original founders of the organization were Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière, Jean-Jacques Olier and Pierre Chevrier. They were later joined by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance. The organization's mission was to convert the Indigenous population to Christianity and found a Christian settlement, which would be later known as Ville-Marie.