Gneiss is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. Gneiss is formed by high temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Orthogneiss is gneiss derived from igneous rock. Paragneiss is gneiss derived from sedimentary rock. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures and pressures than schist. Gneiss nearly always shows a banded texture characterized by alternating darker and lighter colored bands and without a distinct foliation.

The Cuillin is a range of rocky mountains located on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. The main Cuillin ridge is also known as the Black Cuillin to distinguish it from the Red Cuillin, which lie to the east of Glen Sligachan.

The Moine Thrust Belt or Moine Thrust Zone is a linear tectonic feature in the Scottish Highlands which runs from Loch Eriboll on the north coast 190 kilometres (120 mi) south-west to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye. The thrust belt consists of a series of thrust faults that branch off the Moine Thrust itself. Topographically, the belt marks a change from rugged, terraced mountains with steep sides sculptured from weathered igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rocks in the west to an extensive landscape of rolling hills over a metamorphic rock base to the east. Mountains within the belt display complexly folded and faulted layers and the width of the main part of the zone varies up to 10 kilometres (6.2 mi), although it is significantly wider on Skye.

The geology of Scotland is unusually varied for a country of its size, with a large number of differing geological features. There are three main geographical sub-divisions: the Highlands and Islands is a diverse area which lies to the north and west of the Highland Boundary Fault; the Central Lowlands is a rift valley mainly comprising Palaeozoic formations; and the Southern Uplands, which lie south of the Southern Uplands Fault, are largely composed of Silurian deposits.

In geology, the term Torridonian is the informal name for the Torridonian Group, a series of Mesoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic arenaceous and argillaceous sedimentary rocks, which occur extensively in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. The strata of the Torridonian Group are particularly well exposed in the district of upper Loch Torridon, a circumstance which suggested the name Torridon Sandstone, first applied to these rocks by James Nicol. Stratigraphically, they lie unconformably on gneisses of the Lewisian complex and their outcrop extent is restricted to the Hebridean Terrane.

The geology of Jersey is characterised by the Late Proterozoic Brioverian volcanics, the Cadomian Orogeny, and only small signs of later deposits from the Cambrian and Quaternary periods. The kind of rocks go from conglomerate to shale, volcanic, intrusive and plutonic igneous rocks of many compositions, and metamorphic rocks as well, thus including most major types.

The Moine Supergroup is a sequence of Neoproterozoic metamorphic rocks that form the dominant outcrop of the Scottish Highlands between the Moine Thrust Belt to the northwest and the Great Glen Fault to the southeast. The sequence is metasedimentary in nature and was metamorphosed and deformed in a series of tectonic events during the Late Proterozoic and Early Paleozoic. It takes its name from A' Mhòine, a peat bog in northern Sutherland.

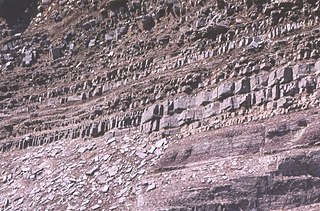

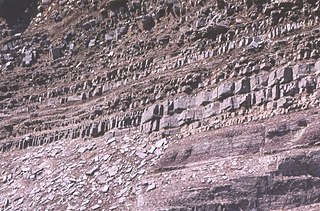

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean Terrane and the North Atlantic Craton. These rocks are of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic age, ranging from 3.0–1.7 Ga. They form the basement on which the Torridonian and Moine Supergroup sediments were deposited. The Lewisian consists mainly of granitic gneisses with a minor amount of supracrustal rocks. Rocks of the Lewisian complex were caught up in the Caledonian orogeny, appearing in the hanging walls of many of the thrust faults formed during the late stages of this tectonic event.

The Hebridean Terrane is one of the terranes that form part of the Caledonian orogenic belt in northwest Scotland. Its boundary with the neighbouring Northern Highland Terrane is formed by the Moine Thrust Belt. The basement is formed by Archaean and Paleoproterozoic gneisses of the Lewisian complex, unconformably overlain by the Neoproterozoic Torridonian sediments, which in turn are unconformably overlain by a sequence of Cambro–Ordovician sediments. It formed part of the Laurentian foreland during the Caledonian continental collision.

The Great Estuarine Group is a sequence of rocks which outcrop around the coast of the West Highlands of Scotland. Laid down in the Hebrides Basin during the middle Jurassic, they are the rough time equivalent of the Inferior and Great Oolite Groups found in southern England.

The Okavango Dyke Swarm is a giant dyke swarm of the Karoo Large Igneous Province in northeast Botswana, southern Africa. It consists of a group of Proterozoic and Jurassic dykes, trending east-southeast across Botswana, spanning a region nearly 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) long and 110 kilometres (68 mi) wide. The Jurassic dykes were formed approximately 179 million years ago, composed of mainly tholeiitic mafic rocks. The formation is related to the magmatism at the Karoo triple junction, induced by the plate tectonic break up of the Gondwana supercontinent in the early Jurassic.

The geology of Nigeria formed beginning in the Archean and Proterozoic eons of the Precambrian. The country forms the Nigerian Province and more than half of its surface is igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rock from the Precambrian. Between 2.9 billion and 500 million years ago, Nigeria was affected by three major orogeny mountain-building events and related igneous intrusions. Following the Pan-African orogeny, in the Cambrian at the time that multi-cellular life proliferated, Nigeria began to experience regional sedimentation and witnessed new igneous intrusions. By the Cretaceous period of the late Mesozoic, massive sedimentation was underway in different basins, due to a large marine transgression. By the Eocene, in the Cenozoic, the region returned to terrestrial conditions.

The geology of Bosnia & Herzegovina is the study of rocks, minerals, water, landforms and geologic history in the country. The oldest rocks exposed at or near the surface date to the Paleozoic and the Precambrian geologic history of the region remains poorly understood. Complex assemblages of flysch, ophiolite, mélange and igneous plutons together with thick sedimentary units are a defining characteristic of the Dinaric Alps, also known as the Dinaride Mountains, which dominate much of the country's landscape.

The geology of North Macedonia includes the study of rocks dating to the Precambrian and a wide-array of volcanic, sedimentary and metamorphic rocks formed in the last 541 million years.

The geology of Missouri includes deep Precambrian basement rocks formed within the last two billion years and overlain by thick sequences of marine sedimentary rocks, interspersed with igneous rocks by periods of volcanic activity. Missouri is a leading producer of lead from minerals formed in Paleozoic dolomite.

The geology of Uzbekistan consists of two microcontinents and the remnants of oceanic crust, which fused together into a tectonically complex but resource rich land mass during the Paleozoic, before becoming draped in thick, primarily marine sedimentary units.

The geology of Thailand includes deep crystalline metamorphic basement rocks, overlain by extensive sandstone, limestone, turbidites and some volcanic rocks. The region experienced complicated tectonics during the Paleozoic, long-running shallow water conditions and then renewed uplift and erosion in the past several million years ago.

The geology of Israel includes igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rocks from the Precambrian overlain by a lengthy sequence of sedimentary rocks extending up to the Pleistocene and overlain with alluvium, sand dunes and playa deposits.

The geology of Yukon includes sections of ancient Precambrian Proterozoic rock from the western edge of the proto-North American continent Laurentia, with several different island arc terranes added through the Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic, driving volcanism, pluton formation and sedimentation.

The geology of the Isle of Mull in Scotland is dominated by the development during the early Palaeogene period of a ‘volcanic central complex’ associated with the opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The bedrock of the larger part of the island is formed by basalt lava flows ascribed to the Mull Lava Group erupted onto a succession of Mesozoic sedimentary rocks during the Palaeocene epoch.