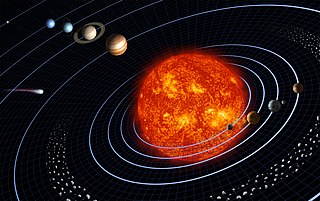

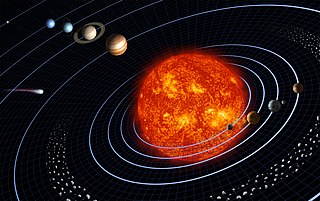

The giant planets constitute a diverse type of planet much larger than Earth. They are usually primarily composed of low-boiling-point materials (volatiles), rather than rock or other solid matter, but massive solid planets can also exist. There are four known giant planets in the Solar System: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Many extrasolar giant planets have been identified orbiting other stars.

Brown dwarfs are substellar objects that are not massive enough to sustain nuclear fusion of ordinary hydrogen (1H) into helium in their cores, unlike a main-sequence star. Instead, they have a mass between the most massive gas giant planets and the least massive stars, approximately 13 to 80 times that of Jupiter (MJ). However, they can fuse deuterium (2H) and the most massive ones can fuse lithium (7Li).

A terrestrial planet, telluric planet, solid planet, or rocky planet, is a planet that is composed primarily of silicate rocks or metals. Within the Solar System, the terrestrial planets accepted by the IAU are the inner planets closest to the Sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. Among astronomers who use the geophysical definition of a planet, two or three planetary-mass satellites – Earth's Moon, Io, and sometimes Europa – may also be considered terrestrial planets; and so may be the rocky protoplanet-asteroids Pallas and Vesta. The terms "terrestrial planet" and "telluric planet" are derived from Latin words for Earth, as these planets are, in terms of structure, Earth-like. Terrestrial planets are generally studied by geologists, astronomers, and geophysicists.

A red dwarf is the smallest and coolest kind of star on the main sequence. Red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star in the Milky Way, at least in the neighborhood of the Sun, but because of their low luminosity, individual red dwarfs cannot be easily observed. From Earth, not one star that fits the stricter definitions of a red dwarf is visible to the naked eye. Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to the Sun, is a red dwarf, as are fifty of the sixty nearest stars. According to some estimates, red dwarfs make up three-quarters of the stars in the Milky Way.

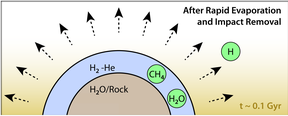

Chthonian planets are a hypothetical class of celestial objects resulting from the stripping away of a gas giant's hydrogen and helium atmosphere and outer layers, which is called hydrodynamic escape. Such atmospheric stripping is a likely result of proximity to a star. The remaining rocky or metallic core would resemble a terrestrial planet in many respects.

A carbon planet is a theoretical type of planet that contains more carbon than oxygen. Carbon is the fourth most abundant element in the universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen.

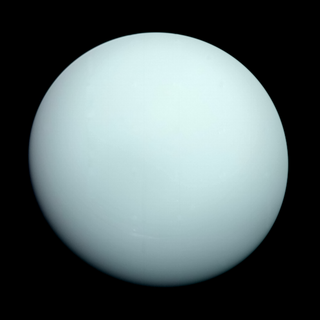

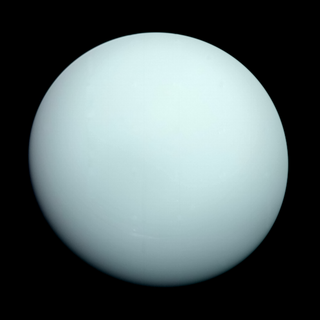

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System: Uranus and Neptune.

Sudarsky's classification of gas giants for the purpose of predicting their appearance based on their temperature was outlined by David Sudarsky and colleagues in the paper Albedo and Reflection Spectra of Extrasolar Giant Planets and expanded on in Theoretical Spectra and Atmospheres of Extrasolar Giant Planets, published before any successful direct or indirect observation of an extrasolar planet atmosphere was made. It is a broad classification system with the goal of bringing some order to the likely rich variety of extrasolar gas-giant atmospheres.

55 Cancri e is an exoplanet in the orbit of its Sun-like host star 55 Cancri A. The mass of the exoplanet is about 8.63 Earth masses and its diameter is about twice that of the Earth, thus making it the first super-Earth discovered around a main sequence star, predating Gliese 876 d by a year. It takes fewer than 18 hours to complete an orbit and is the innermost-known planet in its planetary system. 55 Cancri e was discovered on 30 August 2004. However, until the 2010 observations and recalculations, this planet had been thought to take about 2.8 days to orbit the star. In October 2012, it was announced that 55 Cancri e could be a carbon planet.

Gliese 436 b is a Neptune-sized exoplanet orbiting the red dwarf Gliese 436. It was the first hot Neptune discovered with certainty and was among the smallest-known transiting planets in mass and radius, until the much smaller Kepler exoplanet discoveries began circa 2010.

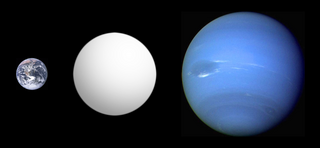

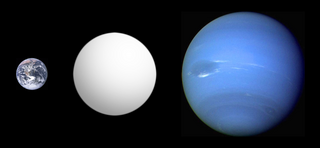

A super-Earth is a type of exoplanet with a mass higher than Earth's, but substantially below those of the Solar System's ice giants, Uranus and Neptune, which are 14.5 and 17 times Earth's, respectively. The term "super-Earth" refers only to the mass of the planet, and so does not imply anything about the surface conditions or habitability. The alternative term "gas dwarfs" may be more accurate for those at the higher end of the mass scale, although "mini-Neptunes" is a more common term.

The study of extraterrestrial atmospheres is an active field of research, both as an aspect of astronomy and to gain insight into Earth's atmosphere. In addition to Earth, many of the other astronomical objects in the Solar System have atmospheres. These include all the gas giants, as well as Mars, Venus and Titan. Several moons and other bodies also have atmospheres, as do comets and the Sun. There is evidence that extrasolar planets can have an atmosphere. Comparisons of these atmospheres to one another and to Earth's atmosphere broaden our basic understanding of atmospheric processes such as the greenhouse effect, aerosol and cloud physics, and atmospheric chemistry and dynamics.

This page describes exoplanet orbital and physical parameters.

A hot Neptune or Hoptune is a type of giant planet with a mass similar to that of Uranus or Neptune orbiting close to its star, normally within less than 1 AU. The first hot Neptune to be discovered with certainty was Gliese 436 b in 2007, an exoplanet about 33 light years away. Recent observations have revealed a larger potential population of hot Neptunes in the Milky Way than was previously thought. Hot Neptunes may have formed either in situ or ex situ.

Gliese 1214 b is an exoplanet that orbits the star Gliese 1214, and was discovered in December 2009. Its parent star is 48 light-years from the Sun, in the constellation Ophiuchus. As of 2017, GJ 1214 b is the most likely known candidate for being an ocean planet. For that reason, scientists often call the planet a "waterworld".

HR 8799 e is a large exoplanet, orbiting the star HR 8799, which lies 129 light-years from Earth. This gas giant is between 5 and 10 times the mass of Jupiter, the largest planet in the Planetary System. Due to their young age and high temperature all four discovered planets in the HR 8799 system are large, compared to all gas giants in the Solar System.

A Mini-Neptune is a planet less massive than Neptune but resembling Neptune in that it has a thick hydrogen–helium atmosphere, probably with deep layers of ice, rock or liquid oceans.

A gas giant is a giant planet composed mainly of hydrogen and helium. Gas giants are also called failed stars because they contain the same basic elements as a star. Jupiter and Saturn are the gas giants of the Solar System. The term "gas giant" was originally synonymous with "giant planet". However, in the 1990s, it became known that Uranus and Neptune are really a distinct class of giant planets, being composed mainly of heavier volatile substances. For this reason, Uranus and Neptune are now often classified in the separate category of ice giants.

HD 219134 b is one of at least five exoplanets orbiting HD 219134, a main-sequence star in the constellation of Cassiopeia. HD 219134 b has a size of about 1.6 REarth, and a density of 6.4 g/cm3 and orbits at 21.25 light-years away. The exoplanet was initially detected by the instrument HARPS-N of the Italian Telescopio Nazionale Galileo via the radial velocity method and subsequently observed by the Spitzer telescope as transiting in front of its star. The exoplanet has a mass of about 4.5 times that of Earth and orbits its host star every three days. In 2017, it was found that the planet likely hosts an atmosphere.

GJ 3470 b, occasionally Gliese 3470 b, is an exoplanet orbiting the star GJ 3470, located in the constellation Cancer. With a mass of just under 14 Earth-masses and a radius approximately 4.3 times that of Earth's, it is likely something akin to Neptune despite the initially strong belief that the planet was not covered in clouds like the gas giants in the Solar System.