Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one biological sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with, and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex. These two forms of selection mean that some individuals have greater reproductive success than others within a population, for example because they are more attractive or prefer more attractive partners to produce offspring. Successful males benefit from frequent mating and monopolizing access to one or more fertile females. Females can maximise the return on the energy they invest in reproduction by selecting and mating with the best males.

Amplexus is a type of mating behavior exhibited by some externally fertilizing species in which a male grasps a female with his front legs as part of the mating process, and at the same time or with some time delay, he fertilizes the eggs, as they are released from the female's body. In amphibians, females may be grasped by the head, waist, or armpits, and the type of amplexus is characteristic of some taxonomic groups.

A lek is an aggregation of male animals gathered to engage in competitive displays and courtship rituals, known as lekking, to entice visiting females which are surveying prospective partners with which to mate. It can also refer to a space used by displaying males to defend their own share of territory for the breeding season. A lekking species is characterised by male displays, strong female mate choice, and the conferring of indirect benefits to males and reduced costs to females. Although most prevalent among birds such as black grouse, lekking is also found in a wide range of vertebrates including some bony fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and arthropods including crustaceans and insects.

Behavioral ecology, also spelled behavioural ecology, is the study of the evolutionary basis for animal behavior due to ecological pressures. Behavioral ecology emerged from ethology after Niko Tinbergen outlined four questions to address when studying animal behaviors: What are the proximate causes, ontogeny, survival value, and phylogeny of a behavior?

Hylidae is a wide-ranging family of frogs commonly referred to as "tree frogs and their allies". However, the hylids include a diversity of frog species, many of which do not live in trees, but are terrestrial or semiaquatic.

The American green tree frog is a common arboreal species of New World tree frog belonging to the family Hylidae. This nocturnal insectivore is moderately sized and has a bright green to reddish-brown coloration. Commonly found in the central and southeastern United States, the frog lives in open canopy forests with permanent water sources and abundant vegetation. The American green tree frog is strictly aquatic during the hibernating and mating seasons. When defending its territory, the frog either emits aggressive call signals or resolves to grapple with intruders, seldom leading to injury or death. To avoid predation, the frog will leap into the water or jump into the treetops.

Hyla japonica, commonly known as the Japanese tree frog, is a species of anuran native to Japan, China, and Korea. H. japonica is unique in its ability to withstand extreme cold, with some individuals showing cold resistance at temperatures as low as −30 °C for up to 120 days. H. japonica are not currently facing any notable risk of extinction and are classified by the IUCN as a species of "least concern". Notably, H. japonica have been sent to space in a study that explored the effect of microgravity on H. japonica. Hyla japonica is synonymous with Dryophytes japonicus.

The gray treefrog is a species of small arboreal holarctic tree frog native to much of the eastern United States and southeastern Canada.

Cope's gray treefrog is a species of treefrog found in the United States and Canada. It is almost indistinguishable from the gray treefrog, and shares much of its geographic range. Both species are variable in color, mottled gray to gray-green, resembling the bark of trees. These are treefrogs of woodland habitats, though they will sometimes travel into more open areas to reach a breeding pond. The only readily noticeable difference between the two species is the mating call — Cope's has a faster-paced and slightly higher-pitched call than D. versicolor. In addition, D. chrysoscelis is reported to be slightly smaller, more arboreal, and more tolerant of dry conditions than D. versicolor.

Teleogryllus oceanicus, commonly known as the Australian, Pacific or oceanic field cricket, is a cricket found across Oceania and in coastal Australia from Carnarvon in Western Australia and Rockhampton in north-east Queensland

Dryophytes gratiosus, commonly known as the barking tree frog, is a species of tree frog endemic to the south-eastern United States. Formerly known as Hyla gratiosa.

Mate choice is one of the primary mechanisms under which evolution can occur. It is characterized by a "selective response by animals to particular stimuli" which can be observed as behavior. In other words, before an animal engages with a potential mate, they first evaluate various aspects of that mate which are indicative of quality—such as the resources or phenotypes they have—and evaluate whether or not those particular trait(s) are somehow beneficial to them. The evaluation will then incur a response of some sort.

Dendropsophus ebraccatus, also known as the hourglass treefrog, referring to the golden-brown hourglass shape seen surrounded by skin yellow on its back. Their underbellies are yellow. Their arms and lower legs usually display bold patterns while their upper legs or thighs are light yellow giving them the appearance of wearing no pants. The species name "ebraccata" translates to "without trousers" in Latin.

The Italian tree frog is a species of frog in the family Hylidae, found in Italy, Slovenia, Switzerland, and possibly San Marino. Its natural habitats are temperate forests, rivers, intermittent rivers, freshwater marshes, intermittent freshwater marshes, arable land, and urban areas. It is threatened by habitat loss.

Rosenberg's treefrog, also known as Rosenberg's gladiator frog or Rosenberg's gladiator treefrog, is a species of frog in the family of tree frogs (Hylidae) and genus of gladiator frogs (Boana) found in Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Trinidad and Tobago and north-western Ecuador. Its scientific name is a testimony to Mr. W. F. H. Rosenberg who collected the type series, and its common name refers to the aggressiveness of males of the species.

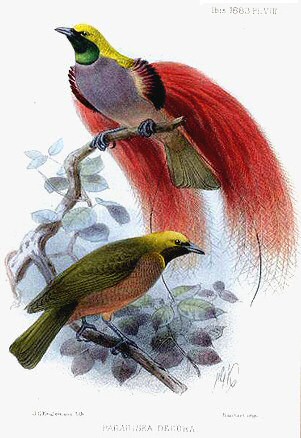

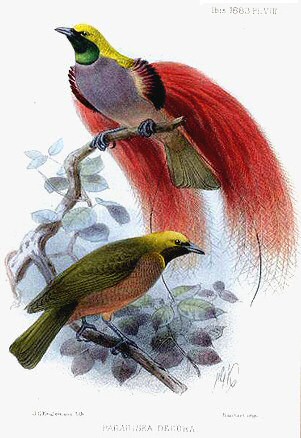

A courtship display is a set of display behaviors in which an animal, usually a male, attempts to attract a mate; the mate exercises choice, so sexual selection acts on the display. These behaviors often include ritualized movement ("dances"), vocalizations, mechanical sound production, or displays of beauty, strength, or agonistic ability.

Female copulatory vocalizations, also called female copulation calls or coital vocalizations, are produced by female primates, including human females, and female non-primates. They are not purposeful, but instead are evolutionary and are spontaneously produced by female primates, including women, to encourage her partner to produce good-quality sperm during the mating process. Copulatory vocalizations usually occur during copulation and are hence related to sexual activity. Vocalizations that occur before intercourse, for the purpose of attracting mates, are known as mating calls.

Sexual selection in amphibians involves sexual selection processes in amphibians, including frogs, salamanders and newts. Prolonged breeders, the majority of frog species, have breeding seasons at regular intervals where male-male competition occurs with males arriving at the waters edge first in large number and producing a wide range of vocalizations, with variations in depth of calls the speed of calls and other complex behaviours to attract mates. The fittest males will have the deepest croaks and the best territories, with females making their mate choices at least partly based on the males depth of croaking. This has led to sexual dimorphism, with females being larger than males in 90% of species, males in 10% and males fighting for groups of females.

Reproductive interference is the interaction between individuals of different species during mate acquisition that leads to a reduction of fitness in one or more of the individuals involved. The interactions occur when individuals make mistakes or are unable to recognise their own species, labelled as ‘incomplete species recognition'. Reproductive interference has been found within a variety of taxa, including insects, mammals, birds, amphibians, marine organisms, and plants.

The sensory trap hypothesis describes an evolutionary idea that revolves around mating behavior and female mate choice. It is a model of female preference and male sexual trait evolution through what is known as sensory exploitation. Sensory exploitation, or a sensory trap is an event that occurs in nature where male members of a species perform behaviors or display visual traits that resemble a non-sexual stimulus which females are responsive to. This tricks females into engaging with the males, thus creating more mating opportunities for males. What makes it a sensory trap is that these female responses evolved in a non-sexual context, and the male produced stimulus exploits the female response which would not otherwise occur without the mimicked stimulus.