Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised Proconsul skull, an extinct ape which is now believed to be ancestral to humans. She also discovered the robust Zinjanthropus skull at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, eastern Africa. For much of her career she worked with her husband, Louis Leakey, at Olduvai Gorge, where they uncovered fossils of ancient hominines and the earliest hominins, as well as the stone tools produced by the latter group. Mary Leakey developed a system for classifying the stone tools found at Olduvai. She discovered the Laetoli footprints, and at the Laetoli site she discovered hominin fossils that were more than 3.75 million years old.

Nakuru County is a county in Kenya. It is county number 32 out of the 47 Kenyan counties. Nakuru County is a host to Kenya's Fourth City – Nakuru City. On 1 December 2021, President Uhuru Kenyatta awarded a City Charter status to Nakuru, ranking it with Nairobi, Mombasa, and Kisumu as the cities in Kenya. With a population of 2,162,202, it is the third most populous county in Kenya after Nairobi County and Kiambu County, in that order. With an area of 7,496.5 km2, it is Kenya's 19th largest county in size. Until 21 August 2010, it formed part of Rift Valley Province.

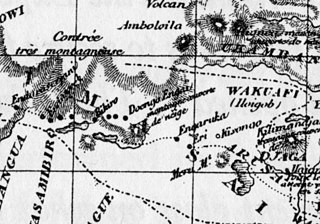

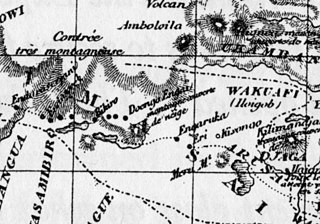

Engaruka is an abandoned system of ruins located in northwest Monduli District in central Arusha Region. The site is in geographical range of the Great Rift Valley of northern Tanzania. Situated in the Monduli District, it is famed for its irrigation and cultivation structures. It is considered one of the most important Iron Age archaeological sites in Tanzania. The site is located in the ward of Engaruka. The site is registered as one of the National Historic Sites of Tanzania.

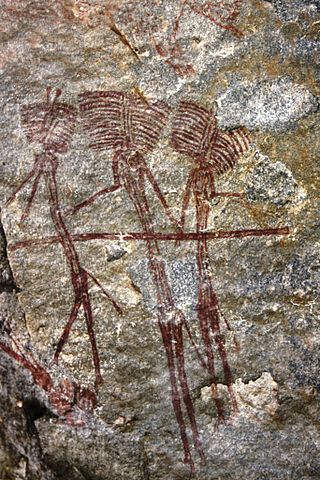

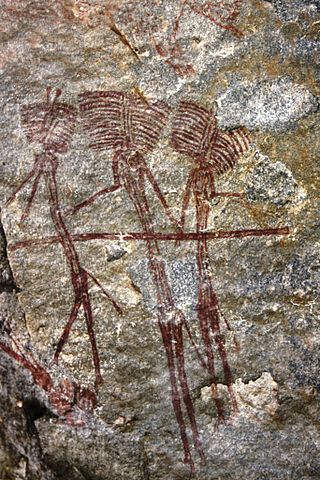

The Kondoa Rock-Art Sites or Kondoa Irangi Rock Paintings are a series of ancient paintings on rockshelter walls in central Tanzania. The Kondoa region was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006 because of its impressive collection of rock art. These sites were named national monuments in 1937 by the Tanzania Antiquities Department. The paintings are located approximately nine kilometres east of the main highway (T5) from Dodoma to Babati, about 20 km north of Kondoa town, in Kondoa District of Dodoma Region, Tanzania. The boundaries of the site are marked by concrete posts. The site is a registered National Historic Sites of Tanzania.

The Urewe culture developed and spread in and around the Lake Victoria region of Africa during the African Iron Age. The culture's earliest dated artefacts are located in the Kagera Region of Tanzania, and it extended as far west as the Kivu region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as far east as the Nyanza and Western provinces of Kenya, and north into Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. Sites from the Urewe culture date from the Early Iron Age, from the 5th century BC to the 6th century AD. The Urewe people certainly did not disappear, and the continuity of institutional life was never completely broken. One of the most striking things about the Early Iron Age pots and smelting furnaces is that some of them were discovered at sites that the local people still associate with royalty, and still more significant is the continuity of language.

Tana ware refers to a type of prehistoric pottery prominent in East Africa that features a variety of designs, including triangular incised lines and single rows of dots. The presence of this pottery is largely regarded as one of the best indicators for early Swahili settlement. This pottery tradition falls chronologically during the Iron Age in East Africa, during the late first millennium AD and spanning several hundred years. The name Tana ware was given because the early discoveries of these types of pottery were along the Tana River in present day Kenya.

The Hyrax Hill site was proclaimed a national monument in 1945 and opened to the public in 1965. This was as a result of startling discoveries of relics by Mrs. Selfe and subsequent archaeological excavations that were carried out by Dr. Mary Leakey in 1938 that revealed substantial findings in different areas of the site and levels of occupations. The late Mrs. Selfe was the owner of the property. The renovation of archaeology exhibit was made possible through the kind sponsorship of Kenya Museum Society and consultation of British Institute in Eastern Africa in collaboration with the National Museums of Kenya. The hill comprises particular importance due to the fact that it encompasses several phases of occupation; it also has a long history of archaeological investigation, which began in 1937 with Mary Leakey.

Ngenyn is a Late Stone Age and/or a Savanna Pastoral Neolithic archaeological site located in the Kapthurin River Basin, which is part of the Tugen Hills, west of Lake Baringo. It falls within the Baringo County in north central Kenya. The occupied area is situated on the floodplain of the River Ndau's confluence with the Sekutionnen River, on a widespread terrace called the Low Terrace, the top of which is about 3m above the level of the modern river. The site was initially discovered by Louis Leakey in 1969. It was visible as a large exposure of bones, stone tools and pottery eroding out of the terrace. The site was excavated in the late 1970s as part of Francoise Hivernel's PhD research. Ngenyn remains the only Late Holocene site excavated in the Lake Baringo Basin and in general very little archaeological work has been done on the Late Holocene within the Baringo County.

Nakuru District was a district in the Rift Valley Province, Kenya. The district capital was Nakuru. With a population of 1,187,039, following the Nairobi region. Nakuru District had an area of 7,242 km².

The Savanna Pastoral Neolithic is a collection of ancient societies that appeared in the Rift Valley of East Africa and surrounding areas during a time period known as the Pastoral Neolithic. They were South Cushitic speaking pastoralists who tended to bury their dead in cairns, whilst their toolkit was characterized by stone bowls, pestles, grindstones and earthenware pots.

The Pastoral Neolithic refers to a period in Africa's prehistory, specifically Tanzania and Kenya, marking the beginning of food production, livestock domestication, and pottery use in the region following the Later Stone Age. The exact dates of this time period remain inexact, but early Pastoral Neolithic sites support the beginning of herding by 5000 BP. In contrast to the Neolithic in other parts of the world, which saw the development of farming societies, the first form of African food production was nomadic pastoralism, or ways of life centered on the herding and management of livestock. The shift from hunting to food production relied on livestock that had been domesticated outside of East Africa, especially North Africa. This period marks the emergence of the forms of pastoralism that are still present. The reliance on livestock herding marks the deviation from hunting-gathering but precedes major agricultural development. The exact movement tendencies of Neolithic pastoralists are not completely understood.

Ngamuriak is an archaeological site located in south-western Kenya. It has been interpreted as an Elmenteitan Pastoral Neolithic settlement. The excavation of this site produced pottery sherds, stone tools with obsidian fragments and obsidian blades, along with large amounts of animal bones.

Gogo Falls is an archaeological site near a former and since 1956 dammed waterfall, located in the Lake Victoria Basin in Migori County, western Kenya. This site is important to archaeology as it includes some of the earliest appearances of artifacts and domestic animals in the area. The findings at the site help to reconstruct the later prehistory around Lake Victoria, including a Pastoral Neolithic occupation by Elmenteitan peoples and a later Iron Age occupation. Artifacts found at the site included pottery and iron artifacts. Through these artifacts some of the cultural traditions of the people who lived near Gogo Falls were discovered.

Njoro River Cave is an archaeological site on the Mau Escarpment, Kenya, that was first excavated in 1938 by Mary Leakey and her husband Louis Leakey. Excavations revealed a mass cremation site created by Elmenteitan pastoralists during the Pastoral Neolithic roughly 3350-3050 BP. Excavations also uncovered pottery, beads, stone bowls, basket work, pestles and flakes. The Leakeys' excavation was one of the earliest to uncover ancient beads and tools in the area and a later investigation in 1950 was the first to use radiocarbon dating in East Africa.

The Elmenteitan culture was a prehistoric lithic industry and pottery tradition with a distinct pattern of land use, hunting and pastoralism that appeared and developed on the western plains of Kenya, East Africa during the Pastoral Neolithic c.3300-1200 BP. It was named by archaeologist Louis Leakey after Lake Elmenteita, a soda lake located in the Great Rift Valley, about 120 km (75 mi) northwest of Nairobi.

Sirikwa holes are saucer-shaped hollows found on hillsides in the western highlands of Kenya and in the elevated stretch of the central Rift Valley around Nakuru. These hollows, each having a diameter of 10–20 metres and an average depth of 2.4 metres, occur in groups, sometimes numbering fewer than ten and at times more than a hundred. Archaeologists believe that construction of these features may have begun in the Iron Age.

The Sirikwa culture was the predominant Kenyan hinterland culture of the Pastoral Iron Age, c.2000 BP. Seen to have developed out of the Elmenteitan culture of the East African Pastoral Neolithic c.3300-1200 BP, it was followed in much of its area by the Kalenjin, Maa, western and central Kenyan communities of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Nasera Rockshelter is an archaeological site located in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area within Ngorongoro District of Arusha Region in northern Tanzania, and it has evidence of Middle Stone Age and Later Stone Age occupations in the Late Pleistocene to early Holocene, and ceramic-bearing Holocene occupations attributed to Kansyore, Nderit, and Savanna Pastoral Neolithic traditions. It was first excavated by Louis Leakey in 1932. A second series of excavations by Michael Mehlman in 1975 and 1976 led to the first comprehensive published study of the shelter, its stratigraphy and chronology, and its abundant material culture, including stone tools, faunal remains, and pottery. Recent work has sought to better understand chronology, lithic technology, mobility and demography, and site formation processes at Nasera Rockshelter. Nasera Rockshelter is considered a key site in eastern Africa for understanding the Middle Stone Age to Later Stone Age transition, and also for the study of the spread of livestock herding during the Pastoral Neolithic. Its chronology and archaeological sequence have been compared to those of other key sites in the region such as Mumba Rockshelter, Kisese II Rockshelter, Panga ya Saidi, and Enkapune ya Muto.

Nderit pottery is a type of ceramic vessel found at archaeological sites in Africa, particularly Tanzania and Kenya. Nderit pottery, previously known as ceramic tradition "Gumban A ware," was initially documented by Louis Leakey in the 1930s at sites in the Central Rift Valley of Kenya.Stylistic characteristics of Nderit pottery discovered in the Central Rift Valley include an exterior decoration of basket-like and triangular markings into the clay’s surface. The vessels here also have intensely scored interiors that do not appear to follow a distinct pattern. Nderit Ware exemplifies the transition from Saharan wavy-line early Holocene pottery towards the basket-like designs of the middle Holocene. Lipid residue found on Nderit pottery can be used to analyze the food products stored in them by early pastoralist societies.

Prospect Farm is an archaeological site on the northern side of Mt. Eburru that has been known to show evidence of prehistoric inhabitants. Excavations have uncovered tool-based artifacts that date to the Middle Stone Age, Later Stone Age, and Pastoral Neolithic that were recognized to be a unique Prospect Industry style. Additionally, bowls were found of the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic. With the large amounts of artifacts found, current work lies in using forms of dating like radiocarbon dating and obsidian hydration to understand the specifics of when these artifacts originated, as well as when the land was used. Current research seeks to build upon this by trying to understand how inhabitants of the Prospect Farm interacted with other groups.