Ungulates are members of the diverse clade Euungulata, which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to be a polyphyletic and thereby invalid clade based on molecular data. As a result, true ungulates had since been reclassified to the newer clade Euungulata in 2001 within the clade Laurasiatheria while Paenungulata has been reclassified to a distant clade Afrotheria. Living ungulates are divided into two orders: Perissodactyla including equines, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and Artiodactyla including cattle, antelope, pigs, giraffes, camels, sheep, deer, and hippopotamuses, among others. Cetaceans such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises are also classified as artiodactyls, although they do not have hooves. Most terrestrial ungulates use the hoofed tips of their toes to support their body weight while standing or moving. Two other orders of ungulates, Notoungulata and Litopterna, both native to South America, became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago.

Paenungulata is a clade of "sub-ungulates", which groups three extant mammal orders: Proboscidea, Sirenia, and Hyracoidea (hyraxes). At least two more possible orders are known only as fossils, namely Embrithopoda and Desmostylia.

The rock hyrax, also called dassie, doop, Cape hyrax, rock rabbit, and coney, is a medium-sized terrestrial mammal native to Africa and the Middle East. Commonly referred to in South Africa as the dassie, it is one of the five living species of the order Hyracoidea, and the only one in the genus Procavia. Rock hyraxes weigh 4–5 kg (8.8–11.0 lb) and have short ears.

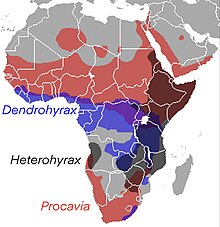

Procavia is a genus of hyraxes. The rock hyrax (P. capensis) is currently the only extant species belonging to this genus, though other species were recognized in the past, including P. habessinica and P. ruficeps, both now relegated to subspecific rank.

Pliohyrax, is a genus of hyracoids. It grew to sizes greatly exceeding those of any living hyrax, though it was by no means the largest member of this family.

Sirenia is the order of placental mammals which comprises modern "sea cows" and their extinct relatives. They are the only extant herbivorous marine mammals and the only group of herbivorous mammals to have become completely aquatic. Sirenians are thought to have a 50-million-year-old fossil record. They attained modest diversity during the Oligocene and Miocene, but have since declined as a result of climatic cooling, oceanographic changes, and human interference. Two genera and four species are extant: Trichechus, which includes the three species of manatee that live along the Atlantic coasts and in rivers and coastlines of the Americas and western Africa, and Dugong, which is found in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

The southern tree hyrax, also known as the southern tree dassie, is a species of mammal in the family Procaviidae. The southern tree hyrax is mainly found in the south central eastern side of Africa.

The tree hyrax or tree dassie is a small nocturnal mammal native to Africa. Distantly related to elephants and sea cows, it comprises the four species in the genus Dendrohyrax, one of only three genera in the family Procaviidae, which is the only living family within the order Hyracoidea.

The western tree hyrax, also called the western tree dassie or Beecroft's tree hyrax, is a species of tree hyrax within the family Procaviidae. It can be distinguished from other hyraxes by short coarse fur, presence of white patch of fur beneath the chin, lack of hair on the rostrum, and lower crowns of the cheek teeth compared to other members of the same genus.

The yellow-spotted rock hyrax or bush hyrax is a species of mammal in the family Procaviidae. It is found in Angola, Botswana, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, southern Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Somalia, northern South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Its natural habitats are dry savanna and rocky areas. Hyrax comes from the Greek word ὕραξ, or shrew-mouse.

Titanohyrax is an extinct genus of large to very large hyrax from the Eocene and Oligocene. Specimens have been discovered in modern-day Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt and Libya. Some species, like T. ultimus, are estimated to be as large as the modern rhinoceros. Titanohyrax species are still poorly known due to their rarity in the fossil record.

The eastern tree hyrax is a species of mammal within the family Procaviidae. The eastern tree hyrax is the most localized of the tree hyrax species, distributed patchily in a narrow band of lowland and montane forests in Kenya and Tanzania and adjacent islands.

Megalohyrax is an extinct hyrax-grouped genus of herbivorous mammal that lived during the Miocene, Oligocene, and Eocene, about 55-11 million years ago. Its fossils have been found in Africa and in Asia Minor.

Microhyrax was a prehistoric genus of herbivorous hyrax-grouped mammal. It lived during the Eocene period from 55.8 to 40.4 million years ago in modern-day Algeria.